Berlin iron jewellery refers to articles of cast-iron jewellery that were made during the early 19th century in Germany. [1]

Contents

Berlin iron jewellery refers to articles of cast-iron jewellery that were made during the early 19th century in Germany. [1]

Prior to production beginning in Berlin very similar jewellery was being produced in Gliwice and France. [2]

The roots of Berlin iron jewellery in Berlin can be traced back to the establishment of the Königliche Eisengiesserei bei Berlin or Royal Berlin Foundry in 1804. [2] The Royal Berlin Foundry started with the production of iron goods such as vases, knife stands, candelabra, bowls, plaques and medallions, as well as more commercial articles such as fences, bridges and garden furniture. The first jewellery items, such as long chains with cast links, were produced in 1806. Later, necklaces consisting of medallions and joined with links and wirework mesh were manufactured. [1] When Napoleon took Berlin in 1806, the moulds appear to have been taken back to France, where further production took place for some years. [3]

The production of iron jewellery reached its peak between 1813 and 1815, when the Prussian royal family urged all citizens to contribute their gold and silver jewellery towards funding the uprising against Napoleon during the War of Liberation. In return the people were given iron jewellery such as brooches and finger rings, often with the inscription Gold gab ich für Eisen (I gave gold for iron), or Für das Wohl des Vaterlands (For the welfare of our country / fatherland), or with a portrait of Frederick William III of Prussia on the back. Until then iron jewellery had only been worn as a symbol of mourning (because of its black colour acquired by treating the castings with linseed cakes) [4] and was worth too little to be alluring, but suddenly it became a symbol of patriotism and loyalty and with its obvious aesthetic appeal, became popular overnight. [1]

The numbers of pieces produced started declining after 1850, but still continued to be manufactured until the end of the century when the fashion ended. [5] Around the start of the decline or just before there appears to have been a shift towards designing the jewellery in a more gothic style. [5]

It is not widely known, but in 1916 another, similar attempt was made in Germany to promote iron jewellery and to fund the German share in the First World War. This was done by exchanging gold jewellery for an iron medallion inscribed with the words: Gold gab ich zur Wehr, Eisen nahm ich zur Ehr (I give gold towards our defence effort and I take iron for honour). This attempt, however, was not as successful. Today, Berlin iron jewellery are collector's items and true pieces are usually found in museums or private collections.

Collections of Berlin iron jewellery are held by among others Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, Neues Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum. [3]

At first the style of the designs, especially during the Napoleonic period, was Neo-Classical, incorporating plenty of fretwork and moulded replicas of cameos. [1]

From 1810 the style changed slightly to a miniature form of Gothic Revival, incorporating the pointed arch and rose widow of the Gothic cathedral, combined with less austere, more naturalistic motifs such as butterflies, trefoils (a plant with three leaflets such as clover) and vine leaves. [1]

The jewellery has a very fine, detailed and lacy appearance. Berlin iron jewellery was lacquered black to prevent the iron from rusting and to enhance its purpose as mourning jewellery. Only a few rare examples were decorated with fine gold, silver settings or polished steel. Some were also set with medallions, imitating the Greek classical scenes on some of the jasperware made by the famous potter Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795), or the portrait medallions of contemporaries made by James Tassie (1735–1799). [1]

Between 1808 and 1848 the Royal Berlin Factory marketed plaques as new year gifts. Known as Neujahr-plaketten (new year reliefs) they generally featured some event relevant to the year in question. [6]

For such intricate detail and thin-sectioned castings to be produced as were done with Berlin iron jewellery, a very pure iron which contained up to 0.7% phosphorus was used. This was done to make the iron slightly more fluid than what it would be when normally molten. Although this type of phosphoric cast iron is rather hard and brittle, strength is not the main purpose of the metal when it is used in jewellery. The molten iron was cast into metal chill moulds. [1]

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content in contrast to that of cast iron. It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions, which give it a wood-like "grain" that is visible when it is etched, rusted, or bent to failure. Wrought iron is tough, malleable, ductile, corrosion resistant, and easily forge welded, but is more difficult to weld electrically.

In printing, type metal refers to the metal alloys used in traditional typefounding and hot metal typesetting. Historically, type metal was an alloy of lead, tin and antimony in different proportions depending on the application, be it individual character mechanical casting for hand setting, mechanical line casting or individual character mechanical typesetting and stereo plate casting. The proportions used are in the range: lead 50‒86%, antimony 11‒30% and tin 3‒20%. Antimony and tin are added to lead for durability while reducing the difference between the coefficients of expansion of the matrix and the alloy. Apart from durability, the general requirements for type-metal are that it should produce a true and sharp cast, and retain correct dimensions and form after cooling down. It should also be easy to cast, at reasonable low melting temperature, iron should not dissolve in the molten metal, and mould and nozzles should stay clean and easy to maintain. Today, Monotype machines can utilize a wide range of different alloys. Mechanical linecasting equipment uses alloys that are close to eutectic.

Woodstock is a market town and civil parish, 8 miles (13 km) north-west of Oxford in West Oxfordshire in the county of Oxfordshire, England. The 2011 Census recorded a parish population of 3,100.

Jet is a type of lignite, the lowest rank of coal, and is a gemstone. Unlike many gemstones, jet is not a mineral, but is rather a mineraloid. It is derived from wood that has changed under extreme pressure.

Die casting is a metal casting process that is characterized by forcing molten metal under high pressure into a mold cavity. The mold cavity is created using two hardened tool steel dies which have been machined into shape and work similarly to an injection mold during the process. Most die castings are made from non-ferrous metals, specifically zinc, copper, aluminium, magnesium, lead, pewter, and tin-based alloys. Depending on the type of metal being cast, a hot- or cold-chamber machine is used.

In the manufacture of metal type used in letterpress printing, a matrix is the mould used to cast a letter, known as a sort. Matrices for printing types were made of copper.

Lost-wax casting – also called investment casting, precision casting, or cire perdue – is the process by which a duplicate sculpture is cast from an original sculpture. Intricate works can be achieved by this method.

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-finished casting products are made from molten pig iron or from scrap.

A parure is a set of various items of matching jewelry, which rose to popularity in early 19th-century Europe.

Bellfounding is the casting and tuning of large bronze bells in a foundry for use such as in churches, clock towers and public buildings, either to signify the time or an event, or as a musical carillon or chime. Large bells are made by casting bell metal in moulds designed for their intended musical pitches. Further fine tuning is then performed using a lathe to shave metal from the bell to produce a distinctive bell tone by sounding the correct musical harmonics.

Investment casting is an industrial process based on lost-wax casting, one of the oldest known metal-forming techniques. The term "lost-wax casting" can also refer to modern investment casting processes.

In casting, a pattern is a replica of the object to be cast, used to form the sand mould cavity into which molten metal is poured during the casting process. Once the pattern has been used to form the sand mould cavity, the pattern is then removed, Molten metal is then poured into the sand mould cavity to produce the casting. The pattern is non consumable and can be reused to produce further sand moulds almost indefinitely.

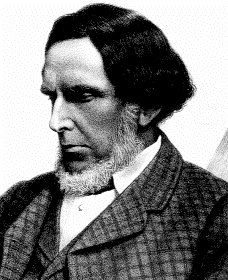

Robert Forester Mushet was a British metallurgist and businessman, born on 8 April 1811, in Coleford, in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, England. He was the youngest son of Scottish parents, Agnes Wilson and David Mushet; an ironmaster, formerly of the Clyde, Alfreton and Whitecliff Ironworks.

Glass casting is the process in which glass objects are cast by directing molten glass into a mould where it solidifies. The technique has been used since the 15th century BCE in both Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Modern cast glass is formed by a variety of processes such as kiln casting or casting into sand, graphite or metal moulds.

A cupola or cupola furnace is a melting device used in foundries that can be used to melt cast iron, Ni-resist iron and some bronzes. The cupola can be made almost any practical size. The size of a cupola is expressed in diameters and can range from 1.5 to 13 feet. The overall shape is cylindrical and the equipment is arranged vertically, usually supported by four legs. The overall look is similar to a large smokestack.

Marcasite jewellery is jewellery made using cut and polished pieces of pyrite as gemstone, and not, as the name suggests, from marcasite.

Shoe buckles are fashion accessories worn by men and women from the mid-17th century through the 18th century to the 19th century. Shoe buckles were made of a variety of materials including brass, steel, silver or silver gilt, and buckles for formal wear were set with diamonds, quartz or imitation jewels.

Openwork or open-work is a term in art history, architecture and related fields for any technique that produces decoration by creating holes, piercings, or gaps that go right through a solid material such as metal, wood, stone, pottery, cloth, leather, or ivory. Such techniques have been very widely used in a great number of cultures.

Robert Ransome was an English maker of agricultural implements. He founded the company later known as Ransomes, Sims & Jefferies.

Cut steel jewellery is a form of jewellery composed of steel that was popular between the 18th century and the end of the 1930s.