Related Research Articles

Art is a diverse range of human activity and its resulting product that involves creative or imaginative talent, generally expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

Aesthetics is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and the nature of taste; and functions as the philosophy of art. Aesthetics examines the philosophy of aesthetic value, which is determined by critical judgments of artistic taste; thus, the function of aesthetics is the "critical reflection on art, culture and nature".

Computer science is the study of computation, information, and automation. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines to applied disciplines.

Film theory is a set of scholarly approaches within the academic discipline of film or cinema studies that began in the 1920s by questioning the formal essential attributes of motion pictures; and that now provides conceptual frameworks for understanding film's relationship to reality, the other arts, individual viewers, and society at large. Film theory is not to be confused with general film criticism, or film history, though these three disciplines interrelate.

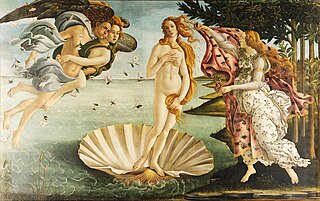

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct from artistic style. The word iconography comes from the Greek εἰκών ("image") and γράφειν.

Aesthetics of music is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of art, beauty and taste in music, and with the creation or appreciation of beauty in music. In the pre-modern tradition, the aesthetics of music or musical aesthetics explored the mathematical and cosmological dimensions of rhythmic and harmonic organization. In the eighteenth century, focus shifted to the experience of hearing music, and thus to questions about its beauty and human enjoyment of music. The origin of this philosophic shift is sometimes attributed to Baumgarten in the 18th century, followed by Kant.

Visual culture is the aspect of culture expressed in visual images. Many academic fields study this subject, including cultural studies, art history, critical theory, philosophy, media studies, Deaf Studies, and anthropology.

The cognitive revolution was an intellectual movement that began in the 1950s as an interdisciplinary study of the mind and its processes, from which emerged a new field known as cognitive science. The preexisting relevant fields were psychology, linguistics, computer science, anthropology, neuroscience, and philosophy. The approaches used were developed within the then-nascent fields of artificial intelligence, computer science, and neuroscience. In the 1960s, the Harvard Center for Cognitive Studies and the Center for Human Information Processing at the University of California, San Diego were influential in developing the academic study of cognitive science. By the early 1970s, the cognitive movement had surpassed behaviorism as a psychological paradigm. Furthermore, by the early 1980s the cognitive approach had become the dominant line of research inquiry across most branches in the field of psychology.

Visual sociology is an area of sociology concerned with the visual dimensions of social life.

Gottfried Boehm is a German art historian and philosopher.

Computational visualistics is an interdisciplinary field focused on the use of computers to generate and analyze images.

Wissenschaft is a German-language term that embraces scholarship, research, study, higher education, and academia. Wissenschaft translates exactly into many other languages, e.g. vetenskap in Swedish or nauka in Polish, but there is no exact translation in modern English. The common translation to science can be misleading, depending on the context, because Wissenschaft equally includes humanities (Geisteswissenschaft), and sciences and humanities are mutually exclusive categories in modern English. Wissenschaft includes humanities like history, anthropology, or arts at the same level as sciences like chemistry or psychology. Wissenschaft incorporates scientific and non-scientific inquiry, learning, knowledge, scholarship, and does not necessarily imply empirical research.

Alois Riegl was an Austrian art historian, and is considered a member of the Vienna School of Art History. He was one of the major figures in the establishment of art history as a self-sufficient academic discipline, and one of the most influential practitioners of formalism.

Critical historiography approaches the history of art, literature or architecture from a critical theory perspective. Critical historiography is used by various scholars in recent decades to emphasize the ambiguous relationship between the past and the writing of history. Specifically, it is used as a method by which one understands the past and can be applied in various fields of academic work.

Hans Belting was a German art historian and media theorist with a focus on image science, and this with regard to contemporary art and to the Italian art of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Art history is, briefly, the history of art—or the study of a specific type of objects created in the past.

World art studies is an expression used to define studies in the discipline of art history, which focus on the history of visual arts worldwide, its methodology, concepts and approach. The expression is also used within the academic curricula as title for specific art history courses and schools.

Horst Bredekamp is a German art historian and visual historian.

Pathosformel or "pathos formula" is a term coined by the German art historian and cultural theorist Aby Warburg (1866–1929) in his research on the afterlife of antiquity. It is described as "the primitive words of passionate gesture language" and the "emotionally charged visual trope[s] that recur throughout images in Western Europe. While the term is associated with formalism, Warburg restricts the concept to cultural-psychological themes, as he held "an honest disgust of aestheticizing art history". Despite its name, pathosformel does not provide a calculable formula to identify visual links among images. Instead, it calls on collective and individual imagination to find such links apart from those based on age, type, size, or origin. In historian Kurt Forster's words, "it exerts its control over existing figurations in a way that endows them with new, 'sign-giving' qualities." The art historian Ernst Gombrich, described pathosformel as "the primeval reaction of man to the universal hardships of his existence [that] underlies all his attempts at mental orientation".

The Flower Thrower, Flower Bomber, Rage, or Love is in the Air is a 2003 stencil mural in Beit Sahour in the West Bank by the graffiti artist Banksy, depicting a masked man throwing a bunch of flowers. It is considered one of Banksy's most iconic works; the image has been widely replicated.

References

- Bredekamp, Horst (2003). "A Neglected Tradition? Art History as Bildwissenschaft". Critical Inquiry . 29 (3): 418–428. doi:10.1086/376303. S2CID 161908949.

- Craven, David (2014). "The New German Art History: From Ideological Critique and the Warburg Renaissance to the Bildwissenschaft of the Three Bs". Art in Translation. 6 (2): 129–147. doi:10.2752/175613114X13998876655059. S2CID 192985575.

- Gaiger, Jason (2014). "The Idea of a Universal Bildwissenschaft". Estetika: The Central European Journal of Aesthetics. LI (2): 208–229. doi: 10.33134/eeja.124 .

- Rampley, Matthew (2012). "Bildwissenschaft: Theories of the Image in German-Language Scholarship". In Rampley, Matthew; Lenain, Thierry; Locher, Hubert; Pinotti, Andrea; Schoell-Glass, Charlotte; Zijlmans, Kitty (eds.). Art History and Visual Studies in Europe: Transnational Discourses and National Frameworks. Brill Publishers. pp. 119–134.