Related Research Articles

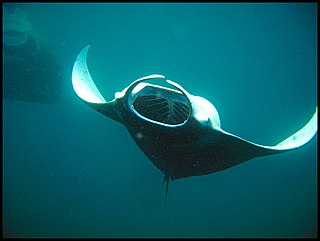

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water that are unable to propel themselves against a current. The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucial source of food to many small and large aquatic organisms, such as bivalves, fish, and baleen whales.

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in freshwater or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term algae encompasses many types of aquatic photosynthetic organisms, both macroscopic multicellular organisms like seaweed and microscopic unicellular organisms like cyanobacteria. Algal bloom commonly refers to the rapid growth of microscopic unicellular algae, not macroscopic algae. An example of a macroscopic algal bloom is a kelp forest.

Clupeidae is a family of clupeiform ray-finned fishes, comprising, for instance, the herrings and sprats. Many members of the family have a body protected with shiny cycloid scales, a single dorsal fin, and a fusiform body for quick, evasive swimming and pursuit of prey composed of small planktonic animals. Due to their small size and position in the lower trophic level of many marine food webs, the levels of methylmercury they bioaccumulate are very low, reducing the risk of mercury poisoning when consumed.

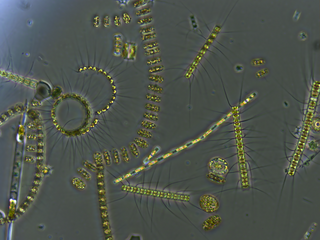

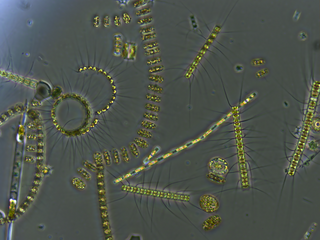

Phytoplankton are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words φυτόν, meaning 'plant', and πλαγκτός, meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community. Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents. Consequently, they drift or are carried along by currents in the ocean, or by currents in seas, lakes or rivers.

Eutrophication is the process by which an entire body of water, or parts of it, becomes progressively enriched with minerals and nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus. It has also been defined as "nutrient-induced increase in phytoplankton productivity". Water bodies with very low nutrient levels are termed oligotrophic and those with moderate nutrient levels are termed mesotrophic. Advanced eutrophication may also be referred to as dystrophic and hypertrophic conditions. Eutrophication can affect freshwater or salt water systems. In freshwater ecosystems it is almost always caused by excess phosphorus. In coastal waters on the other hand, the main contributing nutrient is more likely to be nitrogen, or nitrogen and phosphorus together. This depends on the location and other factors.

Bioaccumulation is the gradual accumulation of substances, such as pesticides or other chemicals, in an organism. Bioaccumulation occurs when an organism absorbs a substance faster than it can be lost or eliminated by catabolism and excretion. Thus, the longer the biological half-life of a toxic substance, the greater the risk of chronic poisoning, even if environmental levels of the toxin are not very high. Bioaccumulation, for example in fish, can be predicted by models. Hypothesis for molecular size cutoff criteria for use as bioaccumulation potential indicators are not supported by data. Biotransformation can strongly modify bioaccumulation of chemicals in an organism.

Isotope analysis is the identification of isotopic signature, abundance of certain stable isotopes of chemical elements within organic and inorganic compounds. Isotopic analysis can be used to understand the flow of energy through a food web, to reconstruct past environmental and climatic conditions, to investigate human and animal diets, for food authentification, and a variety of other physical, geological, palaeontological and chemical processes. Stable isotope ratios are measured using mass spectrometry, which separates the different isotopes of an element on the basis of their mass-to-charge ratio.

Biomagnification, also known as bioamplification or biological magnification, is the increase in concentration of a substance, e.g a pesticide, in the tissues of organisms at successively higher levels in a food chain. This increase can occur as a result of:

Thin layers are concentrated aggregations of phytoplankton and zooplankton in coastal and offshore waters that are vertically compressed to thicknesses ranging from several centimeters up to a few meters and are horizontally extensive, sometimes for kilometers. Generally, thin layers have three basic criteria: 1) they must be horizontally and temporally persistent; 2) they must not exceed a critical threshold of vertical thickness; and 3) they must exceed a critical threshold of maximum concentration. The precise values for critical thresholds of thin layers has been debated for a long time due to the vast diversity of plankton, instrumentation, and environmental conditions. Thin layers have distinct biological, chemical, optical, and acoustical signatures which are difficult to measure with traditional sampling techniques such as nets and bottles. However, there has been a surge in studies of thin layers within the past two decades due to major advances in technology and instrumentation. Phytoplankton are often measured by optical instruments that can detect fluorescence such as LIDAR, and zooplankton are often measured by acoustic instruments that can detect acoustic backscattering such as ABS. These extraordinary concentrations of plankton have important implications for many aspects of marine ecology, as well as for ocean optics and acoustics. Zooplankton thin layers are often found slightly under phytoplankton layers because many feed on them. Thin layers occur in a wide variety of ocean environments, including estuaries, coastal shelves, fjords, bays, and the open ocean, and they are often associated with some form of vertical structure in the water column, such as pycnoclines, and in zones of reduced flow.

The microbial food web refers to the combined trophic interactions among microbes in aquatic environments. These microbes include viruses, bacteria, algae, heterotrophic protists.

Environmental toxicology is a multidisciplinary field of science concerned with the study of the harmful effects of various chemical, biological and physical agents on living organisms. Ecotoxicology is a subdiscipline of environmental toxicology concerned with studying the harmful effects of toxicants at the population and ecosystem levels.

The presence of mercury in fish is a health concern for people who eat them, especially for women who are or may become pregnant, nursing mothers, and young children. Fish and shellfish concentrate mercury in their bodies, often in the form of methylmercury, a highly toxic organomercury compound. This element is known to bioaccumulate in humans, so bioaccumulation in seafood carries over into human populations, where it can result in mercury poisoning. Mercury is dangerous to both natural ecosystems and humans because it is a metal known to be highly toxic, especially due to its neurotoxic ability to damage the central nervous system.

The North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG) is the largest contiguous ecosystem on earth. In oceanography, a subtropical gyre is a ring-like system of ocean currents rotating clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere caused by the Coriolis Effect. They generally form in large open ocean areas that lie between land masses.

Sea foam, ocean foam, beach foam, or spume is a type of foam created by the agitation of seawater, particularly when it contains higher concentrations of dissolved organic matter derived from sources such as the offshore breakdown of algal blooms. These compounds can act as surfactants or foaming agents. As the seawater is churned by breaking waves in the surf zone adjacent to the shore, the surfactants under these turbulent conditions trap air, forming persistent bubbles that stick to each other through surface tension.

Mercury regulation in the United States limit the maximum concentrations of mercury (Hg) that is permitted in air, water, soil, food and drugs. The regulations are promulgated by agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as well as a variety of state and local authorities. EPA published the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) regulation in 2012; the first federal standards requiring power plants to limit emissions of mercury and other toxic gases.

A planktivore is an aquatic organism that feeds on planktonic food, including zooplankton and phytoplankton. Planktivorous organisms encompass a range of some of the planet's smallest to largest multicellular animals in both the present day and in the past billion years; basking sharks and copepods are just two examples of giant and microscopic organisms that feed upon plankton. Planktivory can be an important mechanism of top-down control that contributes to trophic cascades in aquatic and marine systems. There is a tremendous diversity of feeding strategies and behaviors that planktivores utilize to capture prey. Some planktivores utilize tides and currents to migrate between estuaries and coastal waters; other aquatic planktivores reside in lakes or reservoirs where diverse assemblages of plankton are present, or migrate vertically in the water column searching for prey. Planktivore populations can impact the abundance and community composition of planktonic species through their predation pressure, and planktivore migrations facilitate nutrient transport between benthic and pelagic habitats.

Energy, nutrients, and contaminants derived from aquatic ecosystems and transferred to terrestrial ecosystems are termed aquatic-terrestrial subsidies or, more simply, aquatic subsidies. Common examples of aquatic subsidies include organisms that move across habitat boundaries and deposit their nutrients as they decompose in terrestrial habitats or are consumed by terrestrial predators, such as spiders, lizards, birds, and bats. Aquatic insects that develop within streams and lakes before emerging as winged adults and moving to terrestrial habitats contribute to aquatic subsidies. Fish removed from aquatic ecosystems by terrestrial predators are another important example. Conversely, the flow of energy and nutrients from terrestrial ecosystems to aquatic ecosystems are considered terrestrial subsidies; both aquatic subsidies and terrestrial subsidies are types of cross-boundary subsidies. Energy and nutrients are derived from outside the ecosystem where they are ultimately consumed.

Mycoplankton are saprotrophic members of the plankton communities of marine and freshwater ecosystems. They are composed of filamentous free-living fungi and yeasts that are associated with planktonic particles or phytoplankton. Similar to bacterioplankton, these aquatic fungi play a significant role in heterotrophicmineralization and nutrient cycling. Mycoplankton can be up to 20 mm in diameter and over 50 mm in length.

Compared to terrestrial environments, marine environments have biomass pyramids which are inverted at the base. In particular, the biomass of consumers is larger than the biomass of primary producers. This happens because the ocean's primary producers are tiny phytoplankton which grow and reproduce rapidly, so a small mass can have a fast rate of primary production. In contrast, many significant terrestrial primary producers, such as mature forests, grow and reproduce slowly, so a much larger mass is needed to achieve the same rate of primary production.

References

- 1 2 3 Linda M.Campbell; Ross J. Norstrom; Keith A. Hobson; Derek C.G. Muir; Sean Backus; Aaron T. Fisk (December 2005). "Mercury and other trace elements in a pelagic Arctic marine food web (Northwater Polynya, Baffin Bay". Science of the Total Environment. 351–352: 248–263. Bibcode:2005ScTEn.351..247C. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.02.043. PMID 16061271.

- 1 2 Paul C. Pickhardt; Carol L. Folt; Celia Y. Chen; Bjoern Klaue; Joel D.Blum (April 2002). "Algal blooms reduce the uptake of toxic methylmercury in freshwater food webs". PNAS. 99 (7): 4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072531099 . PMC 123663 . PMID 11904388.

- 1 2 Andrew L. Rypel (February 2010). "Mercury Concentrations in Lenthic Fish Populations Related to Ecosystems and Watershed Characteristics". Ambio. 39 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1007/s13280-009-0001-z. PMC 3357655 . PMID 20496648.

- ↑ Ichiro Takeuchi; Noriko Miyoshi; Kaoruko Mizukawa; Hideshige Takada; Tokutaka Ikemoto; Koji Omorp; Kotaro Tsuchiya (May 2009). "Biomagnification profiles of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, alkylphenols, and polychlorinated biphenyls in Tokyo Bay eludcidated by δ13C and δ15N isotope ratios as guides to tropic web structure". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 58 (5): 663–671. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.12.022. PMID 19261300.

- ↑ Kozo Watanabe; Michael T. Monaghan; Yasuhiro Takemon; Tatsuo Omura (May 2008). "Biodilution of heavey metals in a stream macroinvertibrate food web: Evidence from stable isotope analysis". Science of the Total Environment. 394 (1): 57–67. Bibcode:2008ScTEn.394...57W. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.01.006. PMID 18280545.