The Holy Grail is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miraculous healing powers, sometimes providing eternal youth or sustenance in infinite abundance, often guarded in the custody of the Fisher King and located in the hidden Grail castle. By analogy, any elusive object or goal of great significance may be perceived as a "holy grail" by those seeking such.

Wolfram von Eschenbach was a German knight, poet and composer, regarded as one of the greatest epic poets of medieval German literature. As a Minnesinger, he also wrote lyric poetry.

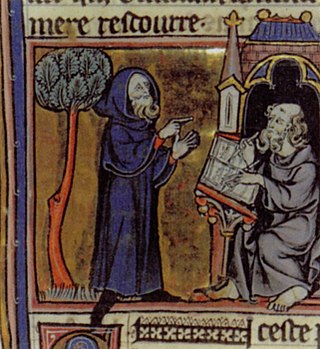

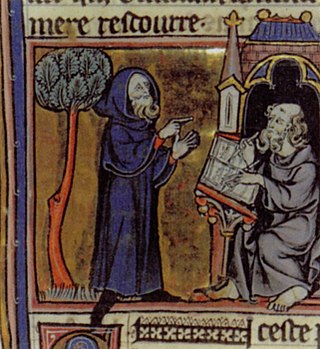

Chrétien de Troyes was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on Arthurian subjects such as Gawain, Lancelot, Perceval and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's chivalric romances, including Erec and Enide, Lancelot, Perceval and Yvain, represent some of the best-regarded works of medieval literature. His use of structure, particularly in Yvain, has been seen as a step towards the modern novel.

The Knights of the Round Table are the legendary knights of the fellowship of King Arthur that first appeared in the Matter of Britain literature in the mid-12th century. The Knights are an order dedicated to ensuring the peace of Arthur's kingdom following an early warring period, entrusted in later years to undergo a mystical quest for the Holy Grail. The Round Table at which they meet is a symbol of the equality of its members, who range from sovereign royals to minor nobles.

Percival, alternatively called Peredur, is a figure in the legend of King Arthur, often appearing as one of the Knights of the Round Table. First mentioned by the French author Chrétien de Troyes in the tale Perceval, the Story of the Grail, he is best known for being the original hero in the quest for the Grail, before being replaced in later literature by Galahad.

Red Knight is a title borne by several characters in Arthurian legend.

The Fisher King is a figure in Arthurian legend, the last in a long line of British kings tasked with guarding the Holy Grail. The Fisher King is both the protector and physical embodiment of his lands, but a wound renders him impotent and his kingdom barren. Unable to walk or ride a horse, he is sometimes depicted as spending his time fishing while he awaits a "chosen one" who can heal him. Versions of the story vary widely, but the Fisher King is typically depicted as being wounded in the groin, legs, or thigh. The healing of these wounds always depends upon the completion of a hero-knight's task.

Floris and Blancheflour is the name of a popular romantic story that was told in the Middle Ages in many different vernacular languages and versions. It first appears in Europe around 1160 in "aristocratic" French. Roughly between the period 1200 and 1350 it was one of the most popular of all the romantic plots.

Gaheris is a Knight of the Round Table in the chivalric romance tradition of Arthurian legend. A nephew of King Arthur, Gaheris is the third son of Arthur's sister or half-sister Morgause and her husband Lot, King of Orkney and Lothian. He is the younger brother of Gawain and Agravain, the older brother of Gareth, and half-brother of Mordred. His figure may have been originally derived from that of a brother of Gawain in the early Welsh tradition, and then later split into a separate character of another brother, today best known as Gareth. German poetry also described him as Gawain's cousin instead of brother.

Robert de Boron was a French poet active around the late 12th and early 13th centuries, notable as the reputed author of the poems Joseph d'Arimathie and Merlin. Although little is known of Robert apart from the poems he allegedly wrote, these works and subsequent prose redactions of them had a strong influence on later incarnations of the Arthurian legend and its prose cycles, in particular through their Christianisation and redefinition of the previously ambiguous Grail motif and the character of Merlin, as well as vastly increasing the prominence of the latter.

Parzival is a medieval chivalric romance by the poet and knight Wolfram von Eschenbach in Middle High German. The poem, commonly dated to the first quarter of the 13th century, centers on the Arthurian hero Parzival and his long quest for the Holy Grail following his initial failure to achieve it.

The Lancelot-Grail Cycle, also known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Pseudo-Map Cycle, is an early 13th-century French Arthurian literary cycle consisting of interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance originally written in Old French. The work of unknown authorship, presenting itself as a chronicle of actual events, retells the legend of King Arthur by focusing on the love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere, the religious quest for the Holy Grail, and the life of Merlin. The highly influential cycle expands on Robert de Boron's "Little Grail Cycle" and the works of Chrétien de Troyes, previously unrelated to each other, by supplementing them with additional details and side stories, as well as lengthy continuations, while tying the entire narrative together into a coherent single tale. Its alternate titles include Philippe Walter's 21st-century edition Le Livre du Graal.

Kyot the Provençal is claimed by Wolfram von Eschenbach to have been a Provençal poet who supplied him with the source for his Arthurian romance Parzival. Wolfram may have been referring to the northern French poet Guiot de Provins, but this identification has proven unsatisfactory. The consensus of the vast majority of scholars today is that Kyot was an invention by Wolfram, and that Wolfram's true sources were Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval, the Story of the Grail and his own abundant creativity.

Perceval, the Story of the Grail is the unfinished fifth verse romance by Chrétien de Troyes, written by him in Old French in the late 12th century. Later authors added 54,000 more lines to the original 9,000 in what are known collectively as the Four Continuations, as well as other related texts. Perceval is the earliest recorded account of what was to become the Quest for the Holy Grail but describes only a golden grail in the central scene, does not call it "holy" and treats a lance, appearing at the same time, as equally significant. Besides the eponymous tale of the grail and the young knight Perceval, the poem and its continuations also tell of the adventures of Gawain and some other knights of King Arthur.

Perceval le Gallois is a 1978 historical drama film written and directed by Éric Rohmer, based on the 12th-century Arthurian romance Perceval, the Story of the Grail by Chrétien de Troyes.

Perlesvaus, also called Li Hauz Livres du Graal, is an Old French Arthurian romance dating to the first decade of the 13th century. It purports to be a continuation of Chrétien de Troyes' unfinished Perceval, the Story of the Grail, but it has been called the least canonical Arthurian tale because of its striking differences from other versions.

"Chevrefoil" is a Breton lai by the medieval poet Marie de France. The eleventh poem in the collection is called The Lais of Marie de France and its subject is an episode from the romance of Tristan and Iseult. The title means "honeysuckle," a symbol of love in the poem. "Chevrefoil" consists of 118 lines and survives in two manuscripts, Harley 978 or MS H, which contains all the Lais, and in Bibliothèque Nationale, nouv. acq. fr. 1104, or MS S.

Merlin is a partly lost French epic poem written by Robert de Boron in Old French and dating from either the end of the 12th or beginning of the 13th century. The author reworked Geoffrey of Monmouth's material on the legendary Merlin, emphasising Merlin's power to prophesy and linking him to the Holy Grail. The poem tells of his origin and early life as a redeemed Antichrist, his role in the birth of Arthur, and how Arthur became King of Britain. Merlin's story relates to Robert's two other reputed Grail poems, Joseph d'Arimathie and Perceval. Its motifs became popular in medieval and later Arthuriana, notably the introduction of the sword in the stone, the redefinition of the Grail, and turning the previously peripheral Merlin into a key character in the legend of King Arthur.

Sir Perceval of Galles is a Middle English Arthurian verse romance whose protagonist, Sir Perceval (Percival), first appeared in medieval literature in Chrétien de Troyes' final poem, the 12th-century Old French Conte del Graal, well over one hundred years before the composition of this work. Sir Perceval of Galles was probably written in the northeast Midlands of England in the early 14th century, and tells a markedly different story to either Chretien's tale or to Robert de Boron's early 13th-century Perceval. Found in only a single manuscript, and told with a comic liveliness, it omits any mention of a graal or a Grail.

Moriaen is a 13th-century Arthurian romance in Middle Dutch. A 4,720-line version is preserved in the vast Lancelot Compilation, and a short fragment exists at the Royal Library at Brussels. The work tells the story of Morien, the Moorish son of Aglovale, one of King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table.