Heroin, also known as diacetylmorphine and diamorphine among other names, is a morphinan opioid substance synthesized from the dried latex of the opium poppy; it is mainly used as a recreational drug for its euphoric effects. Heroin is used medically in several countries to relieve pain, such as during childbirth or a heart attack, as well as in opioid replacement therapy. Medical-grade diamorphine is used as a pure hydrochloride salt. Various white and brown powders sold illegally around the world as heroin are routinely diluted with cutting agents. Black tar heroin is a variable admixture of morphine derivatives—predominantly 6-MAM (6-monoacetylmorphine), which is the result of crude acetylation during clandestine production of street heroin.

Harm reduction, or harm minimization, refers to a range of intentional practices and public health policies designed to lessen the negative social and/or physical consequences associated with various human behaviors, both legal and illegal. Harm reduction is used to decrease negative consequences of recreational drug use and sexual activity without requiring abstinence, recognizing that those unable or unwilling to stop can still make positive change to protect themselves and others.

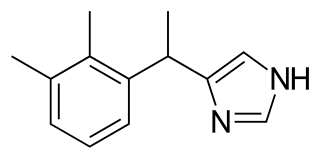

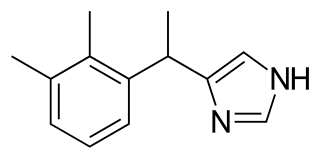

Fentanyl is a highly potent synthetic piperidine opioid primarily used as an analgesic. It is 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine; its primary clinical utility is in pain management for cancer patients and those recovering from painful surgeries. Fentanyl is also used as a sedative. Depending on the method of delivery, fentanyl can be very fast acting and ingesting a relatively small quantity can cause overdose. Fentanyl works by activating μ-opioid receptors. Fentanyl is sold under the brand names Actiq, Duragesic, and Sublimaze, among others.

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist: a medication used to reverse or reduce the effects of opioids. For example, it is used to restore breathing after an opioid overdose. It is also known as Narcan. Effects begin within two minutes when given intravenously, five minutes when injected into a muscle, and ten minutes as a nasal spray. Naloxone blocks the effects of opioids for 30 to 90 minutes.

A needle and syringe programme (NSP), also known as needle exchange program (NEP), is a social service that allows injection drug users (IDUs) to obtain clean and unused hypodermic needles and associated paraphernalia at little or no cost. It is based on the philosophy of harm reduction that attempts to reduce the risk factors for blood-borne diseases such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis.

Supervised injection sites (SIS) or drug consumption rooms (DCRs) are a health and social response to drug-related problems. They are fixed or mobile spaces where people who use drugs are provided with sterile drug use equipment and can use illicit drugs under the supervision of trained staff. They are usually located in areas where there is an open drug scene and where injecting in public places is common. The primary target group for DCR services are people who engage in risky drug use.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a substance use disorder characterized by cravings for opioids, continued use despite physical and/or psychological deterioration, increased tolerance with use, and withdrawal symptoms after discontinuing opioids. This disorder is much more prevalent than first realized. Opioid withdrawal symptoms include nausea, muscle aches, diarrhea, trouble sleeping, agitation, and a low mood. Addiction and dependence are important components of opioid use disorder.

Medetomidine is a veterinary anesthetic drug with potent sedative effects and emerging illicit drug adulterant.

Substance abuse prevention, also known as drug abuse prevention, is a process that attempts to prevent the onset of substance use or limit the development of problems associated with using psychoactive substances. Prevention efforts may focus on the individual or their surroundings. A concept that is known as "environmental prevention" focuses on changing community conditions or policies so that the availability of substances is reduced as well as the demand. Individual Substance Abuse Prevention, also known as drug abuse prevention involves numerous different sessions depending on the individual to help cease or reduce the use of substances. The time period to help a specific individual can vary based upon many aspects of an individual. The type of Prevention efforts should be based upon the individual's necessities which can also vary. Substance use prevention efforts typically focus on minors and young adults — especially between 12–35 years of age. Substances typically targeted by preventive efforts include alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, inhalants, coke, methamphetamine, steroids, club drugs, and opioids. Community advocacy against substance use is imperative due to the significant increase in opioid overdoses in the United States alone. It has been estimated that about one hundred and thirty individuals continue to lose their lives daily due to opioid overdoses alone.

An opioid overdose is toxicity due to excessive consumption of opioids, such as morphine, codeine, heroin, fentanyl, tramadol, and methadone. This preventable pathology can be fatal if it leads to respiratory depression, a lethal condition that can cause hypoxia from slow and shallow breathing. Other symptoms include small pupils and unconsciousness; however, its onset can depend on the method of ingestion, the dosage and individual risk factors. Although there were over 110,000 deaths in 2017 due to opioids, individuals who survived also faced adverse complications, including permanent brain damage.

Michael P. Botticelli is an American public health official who served as the director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) from March 2014 until the end of President Obama's term. He was named acting director after the resignation of Gil Kerlikowske, and received confirmation from the United States Senate in February 2015. Prior to joining ONDCP, he worked in the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Following completion of his service as ONDCP Director, he became the executive director of the Grayken Center for Addiction Medicine at the Boston Medical Center.

Whittier Street Health Center is a Federally Qualified Health Center that provides primary care and support services to primarily low-income, racially and ethnically diverse populations mostly from the Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan, and the South End neighborhoods of Boston, Massachusetts.

There is an ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States, originating out of both medical prescriptions and illegal sources. It has been called "one of the most devastating public health catastrophes of our time". The opioid epidemic unfolded in three waves. The first wave of the epidemic in the United States began in the late 1990s, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), when opioids were increasingly prescribed for pain management, resulting in a rise in overall opioid use throughout subsequent years. The second wave was from an expansion in the heroin market to supply already addicted people. The third wave starting in 2013 was marked by a steep 1,040% increase in the synthetic opioid-involved death rate as synthetic opioids flooded the US market.

The opioid epidemic, also referred to as the opioid crisis, is the rapid increase in the overuse, misuse/abuse, and overdose deaths attributed either in part or in whole to the class of drugs called opiates/opioids since the 1990s. It includes the significant medical, social, psychological, demographic and economic consequences of the medical, non-medical, and recreational abuse of these medications.

Mass. and Cass, also known as Methadone Mile or Recovery Road, is an area in Boston, Massachusetts, located at and around the intersection of Melnea Cass Boulevard and Massachusetts Avenue. Due to its concentration of neighborhood services providing help, the area around Mass. and Cass has long attracted a large number of people struggling with homelessness and drug addiction, especially after the closure of facilities on Long Island in Boston Harbor. It has been characterized as "the epicenter of the region's opioid addiction crisis".

Harm reduction consists of a series of strategies aimed at reducing the negative impacts of drug use on users. It has been described as an alternative to the U.S.'s moral model and disease model of drug use and addiction. While the moral model treats drug use as a morally wrong action and the disease model treats it as a biological or genetic disease needing medical intervention, harm reduction takes a public health approach with a basis in pragmatism. Harm reduction provides an alternative to complete abstinence as a method for preventing and mitigating the negative consequences of drug use and addiction.

Aubri Esters was an American activist for the rights of drug users.

New Jersey's most recent revised policy was issued September 7, 2022 pursuant to P.L.2021, c.152 which authorized opioid antidotes to be dispensed without a prescription or fee. Its goal is to make opioid antidotes widely available, reducing mortality from overdose while decreasing morbidity in conjunction with sterile needle access, fentanyl test strips, and substance use treatment programs. A $67 million grant provided by the Department of Health and Human Services provides funding for naloxone as well as recovery services. This policy enables any person to distribute an opioid antidote to someone they deem at risk of an opioid overdose, alongside information regarding: opioid overdose prevention and recognition, the administration of naloxone, circumstances that warrant calling 911 for assistance with an opioid overdose, and contraindications of naloxone. Instructions on how to perform resuscitation and the appropriate care of an overdose victim after the administration of an opioid antidote should also be included. Community first aid squads, professional organizations, police departments, and emergency departments are required to "leave-behind" naloxone and information with every person who overdosed or is at risk of overdosing.

Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, also known as Boston Healthcare for the Homeless, Healthcare for the Homeless, and BHCHP, is a health care network throughout Greater Boston that provides health care to homeless and formerly homeless individuals and families.

In response to the surging opioid prescription rates by health care providers that contributed to the opioid epidemic in the United States, US states began passing legislation to stifle high-risk prescribing practices. These new laws fell primarily into one of the following four categories:

- Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) enrollment laws: prescribers must enroll in their state's PDMP, an electronic database containing a record of all patients' controlled substance prescriptions

- PDMP query laws: prescribers must check the PDMP before prescribing an opioid

- Opioid prescribing cap laws: opioid prescriptions cannot exceed designated doses or durations

- Pill mill laws: pain clinics are closely regulated and monitored to minimize the prescription of opioids non-medically