Aten also Aton, Atonu, or Itn was the focus of Atenism, the religious system formally established in ancient Egypt by the late Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. Exact dating for the 18th dynasty is contested, though a general date range places the dynasty in the years 1550 to 1292 B.C.E. The worship of Aten and the coinciding rule of Akhenaten are major identifying characteristics of a period within the 18th dynasty referred to as the Amarna Period.

Amarna is an extensive Egyptian archaeological site containing the remains of what was the capital city of the late Eighteenth Dynasty. The city was established in 1346 BC, built at the direction of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, and abandoned shortly after his death in 1332 BC. The name that the ancient Egyptians used for the city is transliterated in English as Akhetaten or Akhetaton, meaning "the horizon of the Aten".

Akhenaten, also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning c. 1353–1336 or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before the fifth year of his reign, he was known as Amenhotep IV.

Neferneferuaten Nefertiti was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for their radical overhaul of state religious policy, in which they promoted the earliest known form of monotheism, Atenism, centered on the sun disc and its direct connection to the royal household. With her husband, she reigned at what was arguably the wealthiest period of ancient Egyptian history. Some scholars believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly as Neferneferuaten after her husband's death and before the ascension of Tutankhamun, although this identification is a matter of ongoing debate. If Nefertiti did rule as Pharaoh, her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.

Kiya was one of the wives of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. Little is known about her, and her actions and roles are poorly documented in the historical record, in contrast to those of Akhenaten's ‘Great royal wife’, Nefertiti. Her unusual name suggests that she may originally have been a Mitanni princess. Surviving evidence demonstrates that Kiya was an important figure at Akhenaten's court during the middle years of his reign, when she had a daughter with him. She disappears from history a few years before her royal husband's death. In previous years, she was thought to be mother of Tutankhamun, but recent DNA evidence suggests this is unlikely.

Meritaten, also spelled Merytaten, Meritaton or Meryetaten, was an ancient Egyptian royal woman of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Her name means "She who is beloved of Aten"; Aten being the sun-deity whom her father, Pharaoh Akhenaten, worshipped. She held several titles, performing official roles for her father and becoming the Great Royal Wife to Pharaoh Smenkhkare, who may have been a brother or son of Akhenaten. Meritaten also may have served as pharaoh in her own right under the name Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten.

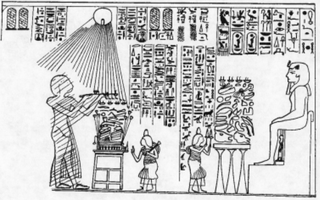

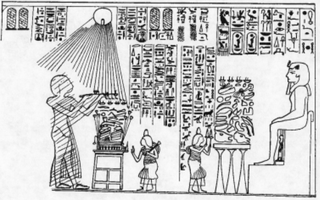

Atenism, also known as the Aten religion, the Amarna religion, and the Amarna heresy, was a religion in ancient Egypt. It was founded by Akhenaten, a pharaoh who ruled the New Kingdom under the Eighteenth Dynasty. The religion is described as monotheistic or monolatristic, although some Egyptologists argue that it was actually henotheistic. Atenism was centred on the cult of Aten, a god depicted as the disc of the Sun. Aten was originally an aspect of Ra, Egypt's traditional solar deity, though he was later asserted by Akhenaten as being the superior of all deities. In the 14th century BC, Atenism was Egypt's state religion for around 20 years, and Akhenaten met the worship of other gods with persecution; he closed many traditional temples, instead commissioning the construction of Atenist temples, and also suppressed religious traditionalists. However, subsequent pharaohs toppled the movement in the aftermath of Akhenaten's death, thereby restoring Egyptian civilization's traditional polytheistic religion. Large-scale efforts were then undertaken to remove from Egypt and Egyptian records any presence or mention of Akhenaten, Atenist temples, and Atenist assertions of a uniquely supreme god.

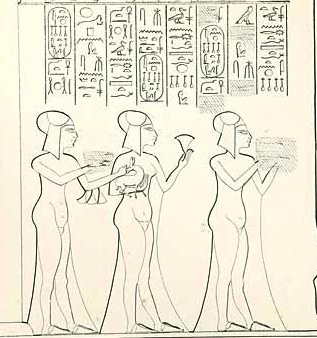

Meketaten was the second daughter of six born to the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti. She likely lived between Year 4 and Year 14 of Akhenaten's reign. Although little is known about her, she is frequently depicted with her sisters accompanying her royal parents in the first two-thirds of the Amarna Period.

Neferneferuaten Tasherit or Neferneferuaten the younger was an ancient Egyptian princess of the 18th Dynasty and the fourth daughter of Pharaoh Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti.

Ankhkheperure-Merit-Neferkheperure/Waenre/Aten Neferneferuaten was a name used to refer to a female pharaoh who reigned toward the end of the Amarna Period during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Her gender is confirmed by feminine traces occasionally found in the name and by the epithet Akhet-en-hyes, incorporated into one version of her nomen cartouche. She is distinguished from the king Smenkhkare who used the same throne name, Ankhkheperure, by the presence of epithets in both cartouches. She is suggested to have been either Meritaten or, more likely, Nefertiti. If this person is Nefertiti ruling as sole pharaoh, it has been theorized by Egyptologist and archaeologist Dr. Zahi Hawass that her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.

Bek or Bak was the first chief royal sculptor during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten. His father Men held the same position under Akhenaten's father Amenhotep III; his mother Roi was a woman from Heliopolis.

The use of urban planning in ancient Egypt is a matter of continuous debate. Because ancient sites usually survive only in fragments, and many ancient Egyptian cities have been continuously inhabited since their original forms, relatively little is actually understood about the general designs of Egyptian towns for any given period.

Setepenre or Sotepenre was an ancient Egyptian princess of the 18th Dynasty; sixth and last daughter of Pharaoh Akhenaten and his chief queen Nefertiti.

Mutbenret (Benretmut) was an Egyptian noblewoman, and said to be the sister of the Great Royal Wife Nefertiti. Her name used to be read as Mutnedjemet. The hieroglyphs for nedjem and bener are similar and so is their meaning. The name is now thought to be Mutbenret however.

Nakhtpaaten or Nakht was an ancient Egyptian vizier during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten of the 18th Dynasty.

Amarna Tomb 5 is an ancient sepulchre in Amarna, Upper Egypt. It was built for the courtier Pentu, and is one of the six Northern tombs at Amarna. The burial is located to the south of the tomb of Meryra. It is very similar to the tomb of Ahmes. The sepulchre is T-shaped and its inner chamber would have served as the burial chamber.

The Stela of Akhenaten and his family is the name for an altar image in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo which depicts the Pharaoh Akhenaten, his queen Nefertiti, and their three children. The limestone stela with the inventory number JE 44865 is 43.5 × 39 cm in size and was discovered by Ludwig Borchardt in Haoue Q 47 at Tell-el Amarna in 1912. When the archaeological finds from Tell-el Amarna were divided on 20 January 1913, Gustave Lefebvre chose this object on behalf of the Egyptian Superintendency for Antiquities instead of the Bust of Nefertiti.

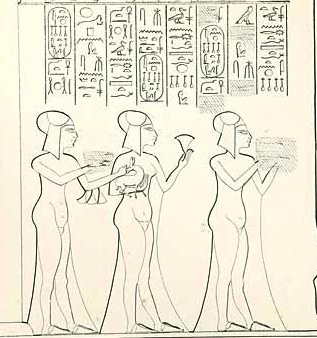

The Amarna Era includes the reigns of Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Tutankhamun and Ay. The period is named after the capital city established by Akhenaten, son of Amenhotep III. Akhenaten started his reign as Amenhotep IV, but changed his name when he discarded all other religions and declared the Aten or sun disc as the only god. He closed all the temples of the other Gods and removed their names from the monuments. Smenkhkare, then Tutankhamun, succeeded Akhenaten. Discarding Akhenten's religious beliefs, Tutankhamun returned to the traditional gods. He died young and was succeeded by Ay. Many kings did their best to remove all traces of the period from the records. The Amarna art is very distinctive: the royal family was portrayed with extended heads, long necks and narrow chests. They had skinny limbs, but heavy hips and thighs, with a marked stomach.

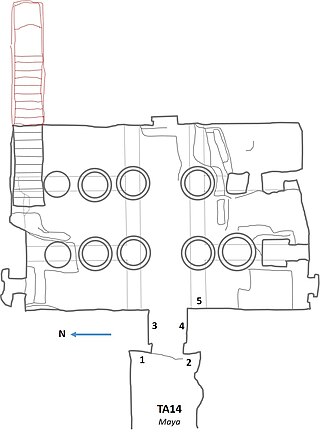

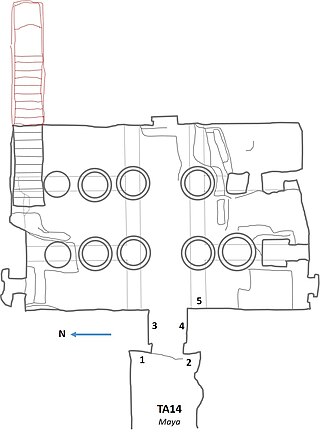

May was an ancient Egyptian official during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten. He was Royal chancellor and fan-bearer at Akhet-Aten, the pharaoh's new capital. He was buried in Tomb EA14 in the southern group of the Amarna rock tombs. Norman de Garis Davies originally published details of the Tomb in 1908 in the Rock Tombs of El Amarna, Part V – Smaller Tombs and Boundary Stelae. The tomb dates to the late 18th Dynasty.

Paatenemheb was an ancient Egyptian official who served under pharaohs Amenhotep III and Akhenaten of the 18th Dynasty.