Related Research Articles

Economics is a social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Keynesian economics are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand strongly influences economic output and inflation. In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy. It is influenced by a host of factors that sometimes behave erratically and impact production, employment, and inflation.

Post-Keynesian economics is a school of economic thought with its origins in The General Theory of John Maynard Keynes, with subsequent development influenced to a large degree by Michał Kalecki, Joan Robinson, Nicholas Kaldor, Sidney Weintraub, Paul Davidson, Piero Sraffa and Jan Kregel. Historian Robert Skidelsky argues that the post-Keynesian school has remained closest to the spirit of Keynes' original work. It is a heterodox approach to economics.

New Keynesian economics is a school of macroeconomics that strives to provide microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new classical macroeconomics.

The Phillips curve is an economic model, named after Bill Phillips, that correlates reduced unemployment with increasing wages in an economy. While Phillips did not directly link employment and inflation, this was a trivial deduction from his statistical findings. Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow made the connection explicit and subsequently Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps put the theoretical structure in place.

Nicholas Kaldor, Baron Kaldor, born Káldor Miklós, was a Hungarian economist. He developed the "compensation" criteria called Kaldor–Hicks efficiency for welfare comparisons (1939), derived the cobweb model, and argued for certain regularities observable in economic growth, which are called Kaldor's growth laws. Kaldor worked alongside Gunnar Myrdal to develop the key concept Circular Cumulative Causation, a multicausal approach where the core variables and their linkages are delineated.

Classical economics, classical political economy, or Smithian economics is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid-19th century. Its main thinkers are held to be Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo, Thomas Robert Malthus, and John Stuart Mill. These economists produced a theory of market economies as largely self-regulating systems, governed by natural laws of production and exchange.

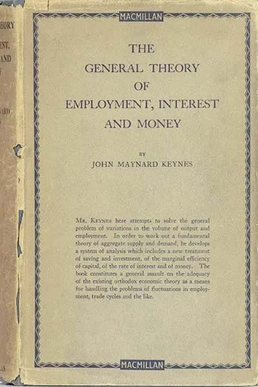

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money is a book by English economist John Maynard Keynes published in February 1936. It caused a profound shift in economic thought, giving macroeconomics a central place in economic theory and contributing much of its terminology – the "Keynesian Revolution". It had equally powerful consequences in economic policy, being interpreted as providing theoretical support for government spending in general, and for budgetary deficits, monetary intervention and counter-cyclical policies in particular. It is pervaded with an air of mistrust for the rationality of free-market decision making.

A macroeconomic model is an analytical tool designed to describe the operation of the problems of economy of a country or a region. These models are usually designed to examine the comparative statics and dynamics of aggregate quantities such as the total amount of goods and services produced, total income earned, the level of employment of productive resources, and the level of prices.

Tobin's q, is the ratio between a physical asset's market value and its replacement value. It was first introduced by Nicholas Kaldor in 1966 in his paper: Marginal Productivity and the Macro-Economic Theories of Distribution: Comment on Samuelson and Modigliani. It was popularised a decade later by James Tobin, who in 1970, described its two quantities as:

One, the numerator, is the market valuation: the going price in the market for exchanging existing assets. The other, the denominator, is the replacement or reproduction cost: the price in the market for newly produced commodities. We believe that this ratio has considerable macroeconomic significance and usefulness, as the nexus between financial markets and markets for goods and services.

In economics, money illusion, or price illusion, is a cognitive bias where money is thought of in nominal, rather than real terms. In other words, the face value of money is mistaken for its purchasing power at a previous point in time. Viewing purchasing power as measured by the nominal value is false, as modern fiat currencies have no intrinsic value and their real value depends purely on the price level. The term was coined by Irving Fisher in Stabilizing the Dollar. It was popularized by John Maynard Keynes in the early twentieth century, and Irving Fisher wrote an important book on the subject, The Money Illusion, in 1928.

International economics is concerned with the effects upon economic activity from international differences in productive resources and consumer preferences and the international institutions that affect them. It seeks to explain the patterns and consequences of transactions and interactions between the inhabitants of different countries, including trade, investment and transaction.

In economics, the wage share or laborshare is the part of national income, or the income of a particular economic sector, allocated to wages (labor). It is related to the capital or profit share, the part of income going to capital, which is also known as the K–Y ratio. The labor share is a key indicator for the distribution of income.

Kaldor's facts are six statements about economic growth, proposed by Nicholas Kaldor in his article from 1961. He described these as "a stylized view of the facts", which coined the term stylized fact.

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Keynes in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). It was formulated most notably by John Hicks (1937), Franco Modigliani (1944), and Paul Samuelson (1948), who dominated economics in the post-war period and formed the mainstream of macroeconomic thought in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

Paul Davidson is an American macroeconomist who has been one of the leading spokesmen of the American branch of the post-Keynesian school in economics. He has actively intervened in important debates on economic policy from a position critical of mainstream economics.

Demand-led growth is the foundation of an economic theory claiming that an increase in aggregate demand will ultimately cause an increase in total output in the long run. This is based on a hypothetical sequence of events where an increase in demand will, in effect, stimulate an increase in supply. This stands in opposition to the common neo-classical theory that demand follows supply, and consequently, that supply determines growth in the long run.

Luigi L. Pasinetti was an Italian economist of the post-Keynesian school. Pasinetti was considered the heir of the "Cambridge Keynesians" and a student of Piero Sraffa and Richard Kahn. Along with them, as well as Joan Robinson, he was one of the prominent members on the "Cambridge, UK" side of the Cambridge capital controversy. His contributions to economics include developing the analytical foundations of neo-Ricardian economics, including the theory of value and distribution, as well as work in the line of Kaldorian theory of growth and income distribution. He also developed the theory of structural change and economic growth, structural economic dynamics and uneven sectoral development.

Macroeconomic theory has its origins in the study of business cycles and monetary theory. In general, early theorists believed monetary factors could not affect real factors such as real output. John Maynard Keynes attacked some of these "classical" theories and produced a general theory that described the whole economy in terms of aggregates rather than individual, microeconomic parts. Attempting to explain unemployment and recessions, he noticed the tendency for people and businesses to hoard cash and avoid investment during a recession. He argued that this invalidated the assumptions of classical economists who thought that markets always clear, leaving no surplus of goods and no willing labor left idle.

The Cambridge capital controversy, sometimes called "the capital controversy" or "the two Cambridges debate", was a dispute between proponents of two differing theoretical and mathematical positions in economics that started in the 1950s and lasted well into the 1960s. The debate concerned the nature and role of capital goods and a critique of the neoclassical vision of aggregate production and distribution. The name arises from the location of the principals involved in the controversy: the debate was largely between economists such as Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa at the University of Cambridge in England and economists such as Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

References

- ↑ Krämer, H. M. (2011). "Bowley's Law: The Diffusion of an Empirical Supposition into Economic Theory". Cahiers d'Économie Politique/Papers in Political Economy. 61 (2): 19–49 [p. 20]. doi:10.3917/cep.061.0019. JSTOR 43107795.

- ↑ Samuelson, P. (1964). Economics: An Introductory Textbook. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 736.

- ↑ Carter, S. (2007). "Real wage productivity elasticity across advanced economies, 1963–1996". Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 29 (4): 573–600 [p. 580]. doi:10.2753/PKE0160-3477290403. S2CID 154904142.

- ↑ Krämer, H. M. (2011). "Bowley's Law: The Diffusion of an Empirical Supposition into Economic Theory". Cahiers d'Économie Politique/Papers in Political Economy. 61 (2): 19–49 [p. 25]. doi:10.3917/cep.061.0019. JSTOR 43107795.

- ↑ Phelps Brown, E. H.; Weber, B. (1953). "Accumulation, Productivity, and Distribution in the British Economy, 1870–1938". Quarterly Journal of Economics . 63 (250): 263–288. doi:10.2307/2227124. JSTOR 2227124.

- ↑ Johnson, D. G. (1954). "The Functional Distribution of Income in the United States, 1850–1952". Review of Economics and Statistics . 36 (2): 175–182. doi:10.2307/1924668. JSTOR 1924668.

- ↑ Kaldor, N. (1957). "A Model of Economic Growth". The Economic Journal . 268 (67): 591–624. doi: 10.2307/2227704 . JSTOR 2227704.

- ↑ Kuznets, S. (1959). "Quantitative Aspects of the Economic Growth of Nations: IV. Distribution of National Income by Factor Shares". Economic Development and Cultural Change. 7 (3 Part 2): 1–100. doi:10.1086/449811. JSTOR 1151715. S2CID 154604869.

- ↑ Solow, R. M. (1958). "A Skeptical Note on the Constancy of Relative Factor Shares". American Economic Review . 48 (4): 618–631. JSTOR 1808271.

- ↑ Krämer, H. M. (2011). "Bowley's Law: The Diffusion of an Empirical Supposition into Economic Theory". Cahiers d'Économie Politique/Papers in Political Economy. 61 (2): 19–49 [p. 27]. doi:10.3917/cep.061.0019. JSTOR 43107795.

- ↑ Gollin, D. (2002). "Getting Income Shares Right". Journal of Political Economy . 110 (2): 458–474. doi:10.1086/338747. S2CID 55836142.

- ↑ Gollin, D. (2008). "Labour's share of income". In Durlauf, S. B.; Blume, L. E. (eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (2nd ed.).

- ↑ Bentolila, S.; Saint-Paul, G. (2003). "Explaining Movements in the Labor Share". Contributions to Macroeconomics. 3 (1): 1–31. doi:10.2202/1534-6005.1103. hdl: 10230/343 . S2CID 155054474.

- ↑ Guscina, A. (2006). "Effects of Globalization on Labor's Share in National Income". IMF Staff Papers. 06 (294): 1. doi: 10.5089/9781451865547.001 . SSRN 956758.

- ↑ Elsby, M. W. L.; et al. (2013). "The Decline of the U.S. Labor Share". Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 47 (2): 1–63. doi:10.1353/eca.2013.0016. hdl: 20.500.11820/33fb6813-7bf1-4c77-a9c9-885a07b7fae4 . S2CID 154352931.

- ↑ Karabournis, L.; Neiman, B. (2014). "The Global Decline of the Labor Share". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 129 (1): 61–103. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.649.273 . doi:10.1093/qje/qjt032.