The British Constitution Association, founded in 1905 as the British Constitutional Association, was a pressure group designed to oppose increasing state regulation, whether from the Liberal Party's New Liberalism or Joseph Chamberlain's proposals for Tariff Reform. [1] It has been described as "a curious mixture of unionist free traders, orthodox poor law administrators, and followers of Herbert Spencer". [2]

Its first president was Lord Hugh Cecil, who was succeeded by Lord Balfour of Burleigh. Its supporters included the constitutional expert A. V. Dicey, Lord Avebury, Lord Courtney, John St Loe Strachey, Professor Flinders Petrie, [3] Thomas Mackay, and Hugh Elliott. [4]

A constitutional monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises authority in accordance with a written or unwritten constitution. Constitutional monarchies differ from absolute monarchies in that they are bound to exercise powers and authorities within limits prescribed by an established legal framework. Constitutional monarchies range from countries such as Liechtenstein, Monaco, Morocco, Jordan, Kuwait and Bahrain, where the constitution grants substantial discretionary powers to the sovereign, to countries such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Spain, Belgium, Sweden, Malaysia and Japan, where the monarch retains significantly less personal discretion in the exercise of their authority.

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government in the United Kingdom. The prime minister chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers, and advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal Prerogative. As modern prime ministers hold office by virtue of their ability to command the confidence of the House of Commons, they typically sit as a Member of Parliament and lead the largest party or a coalition in the House of Commons.

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last prime minister to lead a majority Liberal government, and he played a central role in the design and passage of major liberal legislation and a reduction of the power of the House of Lords. In August 1914, Asquith took Great Britain and the British Empire into the First World War. In 1915, his government was vigorously attacked for a shortage of munitions and the failure of the Gallipoli Campaign. He formed a coalition government with other parties, but failed to satisfy critics. As a result, he was forced to resign in December 1916, and he never regained power.

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Union of South Africa as Orange Free State Province.

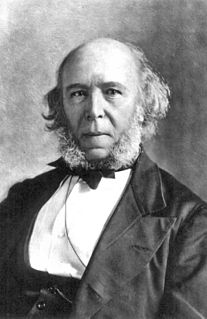

Herbert Spencer was an English philosopher, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism whereby superior physical force shapes history. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in Principles of Biology (1864) after reading Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. The term strongly suggests natural selection, yet Spencer saw evolution as extending into realms of sociology and ethics, so he also supported Lamarckism.

Clause IV is part of the constitution of the UK Labour Party, which sets out the aims and values of the party. The original clause, adopted in 1918, called for common ownership of industry, and proved controversial in later years; Hugh Gaitskell attempted to remove the clause after Labour's loss in the 1959 general election.

Albert Venn Dicey (1835–1922), usually cited as A. V. Dicey, was a British Whig jurist and constitutional theorist. He is most widely known as the author of Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (1885). The principles it expounds are considered part of the uncodified British constitution. He became Vinerian Professor of English Law at Oxford, one of the first Professors of Law at the London School of Economics, and a leading constitutional scholar of his day. Dicey popularised the phrase "rule of law", although its use goes back to the 17th century.

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, was a British Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreign policy in the 1930s, opposing pacifism and promoting rearmament against the German threat, and strongly opposed the appeasement policy of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in 1938. Dalton served in Winston Churchill's wartime coalition cabinet; after the Dunkirk evacuation he was Minister of Economic Warfare, and established the Special Operations Executive. As Chancellor, he pushed his policy of cheap money too hard, and mishandled the sterling crisis of 1947. His political position was already in jeopardy in 1947 when he, seemingly inadvertently, revealed a sentence of the budget to a reporter minutes before delivering his budget speech. Prime Minister Clement Attlee accepted his resignation; Dalton later returned to the cabinet in relatively minor positions.

The three Round Table Conferences of 1930–1932 were a series of peace conferences organized by the British Government and Indian political personalities to discuss constitutional reforms in India. These started in November 1930 and ended in December 1932. They were conducted as per the recommendation of Jinnah to Viceroy Lord Irwin and Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, and by the report submitted by the Simon Commission in May 1930. Demands for Swaraj, or self-rule, in India had been growing increasingly strong. B. R. Ambedkar, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, V. S. Srinivasa Sastri, Sir Muhammad Zafrulla Khan, K. T. Paul and Mirabehn are key participants from India. By the 1930s, many British politicians believed that India needed to move towards dominion status. However, there were significant disagreements between the Indian and the British political parties that the Conferences would not resolve. The key topic was about constitution and India which was mainly discussed in that conference. There were three Round Table Conferences from 1930 to 1932.

The British Empire Union (BEU) was created in the United Kingdom during the First World War, in 1916, after changing its name from the Anti-German Union, which had been founded in April 1915. From December 1922 to summer 1952, it published a regular journal.

Wordsworth Donisthorpe was an English barrister, individualist anarchist and inventor, pioneer of cinematography and chess enthusiast.

Woodstock, sometimes called New Woodstock, was a parliamentary constituency in the United Kingdom named after the town of Woodstock in the county of Oxfordshire.

The Liberal government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that began in 1905 and ended in 1915 consisted of two ministries: the first led by Henry Campbell-Bannerman and the final three by H. H. Asquith.

Thomas Mackay was a British wine merchant and classical liberal.

Keith D. Ewing is professor of public law at King's College London and recognised as a leading scholar in public law, constitutional law, law of democracy, labour law and human rights.

Herbert John Gladstone, 1st Viscount Gladstone, was a British Liberal politician. The youngest son of William Ewart Gladstone, he was Home Secretary from 1905 to 1910 and Governor-General of the Union of South Africa from 1910 to 1914.

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, was a British Labour politician who held a variety of senior positions in the Cabinet. During the inter-war period, he was Minister of Transport during the 1929–1931 Labour Government, then, after losing his seat in Parliament in 1931, became Leader of the London County Council in the 1930s. Returning to the Commons in 1935, he was defeated by Clement Attlee in the Labour leadership election that year, but later acted as Home Secretary in the wartime coalition.

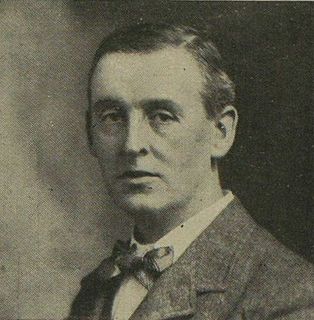

Spencer Leigh Hughes was a British engineer, journalist, and Liberal politician.

Eswatini–Turkey relations are the foreign relations between Eswatini and Turkey. The Turkish ambassador in Pretoria, South Africa is also accredited to Eswatini. Eswatini’s embassy in Brussels is also accredited to Turkey.