Vinegar is an aqueous solution of acetic acid and trace compounds that may include flavorings. Vinegar typically contains from 5% to 8% acetic acid by volume. Usually, the acetic acid is produced by a double fermentation, converting simple sugars to ethanol using yeast, and ethanol to acetic acid using acetic acid bacteria. Many types of vinegar are made, depending on source materials. The product is now mainly used in the culinary arts as a flavorful, acidic cooking ingredient, or in pickling. Various types are used as condiments or garnishes, including balsamic vinegar and malt vinegar.

Winemaking or vinification is the production of wine, starting with the selection of the fruit, its fermentation into alcohol, and the bottling of the finished liquid. The history of wine-making stretches over millennia. There are authentic proofs that suggest that the earliest Wine production took place in Georgia and Iran around 6000 to 5000 B.C. The science of wine and winemaking is known as oenology. A winemaker may also be called a vintner. The growing of grapes is viticulture and there are many varieties of grapes.

Carbonic maceration is a winemaking technique, often associated with the French wine region of Beaujolais, in which whole grapes are fermented in a carbon dioxide rich environment before crushing. Conventional alcoholic fermentation involves crushing the grapes to free the juice and pulp from the skin with yeast serving to convert sugar into ethanol. Carbonic maceration ferments most of the juice while it is still inside the grape, although grapes at the bottom of the vessel are crushed by gravity and undergo conventional fermentation. The resulting wine is fruity with very low tannins. It is ready to drink quickly but lacks the structure for long-term aging. In extreme cases such as Beaujolais nouveau, the period between picking and bottling can be less than six weeks.

White wine is a wine that is fermented without skin contact. The colour can be straw-yellow, yellow-green, or yellow-gold. It is produced by the alcoholic fermentation of the non-coloured pulp of grapes, which may have a skin of any colour. White wine has existed for at least 4,000 years.

Malolactic conversion is a process in winemaking in which tart-tasting malic acid, naturally present in grape must, is converted to softer-tasting lactic acid. Malolactic fermentation is most often performed as a secondary fermentation shortly after the end of the primary fermentation, but can sometimes run concurrently with it. The process is standard for most red wine production and common for some white grape varieties such as Chardonnay, where it can impart a "buttery" flavor from diacetyl, a byproduct of the reaction.

A wine fault is a sensory-associated (organoleptic) characteristic of a wine that is unpleasant, and may include elements of taste, smell, or appearance, elements that may arise from a "chemical or a microbial origin", where particular sensory experiences might arise from more than one wine fault. Wine faults may result from poor winemaking practices or storage conditions that lead to wine spoilage.

The process of fermentation in winemaking turns grape juice into an alcoholic beverage. During fermentation, yeasts transform sugars present in the juice into ethanol and carbon dioxide. In winemaking, the temperature and speed of fermentation are important considerations as well as the levels of oxygen present in the must at the start of the fermentation. The risk of stuck fermentation and the development of several wine faults can also occur during this stage, which can last anywhere from 5 to 14 days for primary fermentation and potentially another 5 to 10 days for a secondary fermentation. Fermentation may be done in stainless steel tanks, which is common with many white wines like Riesling, in an open wooden vat, inside a wine barrel and inside the wine bottle itself as in the production of many sparkling wines.

The use of wine tasting descriptors allows the taster to qualitatively relate the aromas and flavors that the taster experiences and can be used in assessing the overall quality of wine. Wine writers differentiate wine tasters from casual enthusiasts; tasters attempt to give an objective description of the wine's taste, casual enthusiasts appreciate wine but pause their examination sooner than tasters. The primary source of a person's ability to taste wine is derived from their olfactory senses. A taster's own personal experiences play a significant role in conceptualizing what they are tasting and attaching a description to that perception. The individual nature of tasting means that descriptors may be perceived differently among various tasters.

Ann C. Noble is a sensory chemist and retired professor from the University of California, Davis. During her time at the UC Davis Department of Viticulture and Enology, Noble invented the "Aroma Wheel" which is credited with enhancing the public understanding of wine tasting and terminology. At the time of her hiring at UC Davis in 1974, Noble was the first woman hired as a faculty member of the Viticulture department. Noble retired from Davis in 2002 and in 2003 was named Emeritus Professor of Enology. Since retirement she has participated as a judge in the San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition.

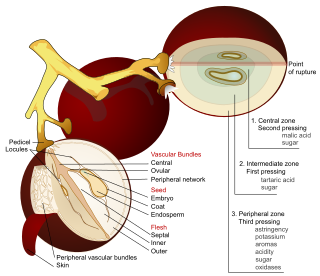

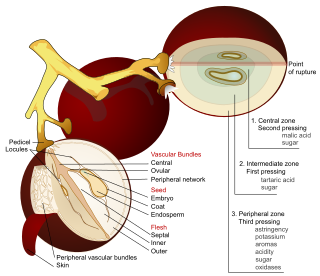

The acids in wine are an important component in both winemaking and the finished product of wine. They are present in both grapes and wine, having direct influences on the color, balance and taste of the wine as well as the growth and vitality of yeast during fermentation and protecting the wine from bacteria. The measure of the amount of acidity in wine is known as the “titratable acidity” or “total acidity”, which refers to the test that yields the total of all acids present, while strength of acidity is measured according to pH, with most wines having a pH between 2.9 and 3.9. Generally, the lower the pH, the higher the acidity in the wine. There is no direct connection between total acidity and pH. In wine tasting, the term “acidity” refers to the fresh, tart and sour attributes of the wine which are evaluated in relation to how well the acidity balances out the sweetness and bitter components of the wine such as tannins. Three primary acids are found in wine grapes: tartaric, malic, and citric acids. During the course of winemaking and in the finished wines, acetic, butyric, lactic, and succinic acids can play significant roles. Most of the acids involved with wine are fixed acids with the notable exception of acetic acid, mostly found in vinegar, which is volatile and can contribute to the wine fault known as volatile acidity. Sometimes, additional acids, such as ascorbic, sorbic and sulfurous acids, are used in winemaking.

The phenolic content in wine refers to the phenolic compounds—natural phenol and polyphenols—in wine, which include a large group of several hundred chemical compounds that affect the taste, color and mouthfeel of wine. These compounds include phenolic acids, stilbenoids, flavonols, dihydroflavonols, anthocyanins, flavanol monomers (catechins) and flavanol polymers (proanthocyanidins). This large group of natural phenols can be broadly separated into two categories, flavonoids and non-flavonoids. Flavonoids include the anthocyanins and tannins which contribute to the color and mouthfeel of the wine. The non-flavonoids include the stilbenoids such as resveratrol and phenolic acids such as benzoic, caffeic and cinnamic acids.

The aging of wine is potentially able to improve the quality of wine. This distinguishes wine from most other consumable goods. While wine is perishable and capable of deteriorating, complex chemical reactions involving a wine's sugars, acids and phenolic compounds can alter the aroma, color, mouthfeel and taste of the wine in a way that may be more pleasing to the taster. The ability of a wine to age is influenced by many factors including grape variety, vintage, viticultural practices, wine region and winemaking style. The condition that the wine is kept in after bottling can also influence how well a wine ages and may require significant time and financial investment. The quality of an aged wine varies significantly bottle-by-bottle, depending on the conditions under which it was stored, and the condition of the bottle and cork, and thus it is said that rather than good old vintages, there are good old bottles. There is a significant mystique around the aging of wine, as its chemistry was not understood for a long time, and old wines are often sold for extraordinary prices. However, the vast majority of wine is not aged, and even wine that is aged is rarely aged for long; it is estimated that 90% of wine is meant to be consumed within a year of production, and 99% of wine within 5 years.

The aromas of wine are more diverse than its flavours. The human tongue is limited to the primary tastes perceived by taste receptors on the tongue – sourness, bitterness, saltiness, sweetness and savouriness. The wide array of fruit, earthy, leathery, floral, herbal, mineral, and woodsy flavour present in wine are derived from aroma notes sensed by the olfactory bulb. In wine tasting, wine is sometimes smelled before taking a sip in order to identify some components of the wine that may be present. Different terms are used to describe what is being smelled. The most basic term is aroma which generally refers to a "pleasant" smell as opposed to odour which refers to an unpleasant smell or possible wine fault. The term aroma may be further distinguished from bouquet which generally refers to the smells that arise from the chemical reactions of fermentation and aging of the wine.

This glossary of winemaking terms lists some of terms and definitions involved in making wine, fruit wine, and mead.

Autolysis in winemaking relates to the complex chemical reactions that take place when a wine spends time in contact with the lees, or dead yeast cells, after fermentation. While for some wines - and all beers - autolysis is undesirable, it is a vital component in shaping the flavors and mouth feel associated with premium Champagne production. The practice of leaving a wine to age on its lees has a long history in winemaking dating back to Roman winemaking. The chemical process and details of autolysis were not originally understood scientifically, but the positive effects such as a creamy mouthfeel, breadlike and floral aromas, and reduced astringency were noticed early in the history of wine.

In winemaking, clarification and stabilization are the processes by which insoluble matter suspended in the wine is removed before bottling. This matter may include dead yeast cells (lees), bacteria, tartrates, proteins, pectins, various tannins and other phenolic compounds, as well as pieces of grape skin, pulp, stems and gums. Clarification and stabilization may involve fining, filtration, centrifugation, flotation, refrigeration, pasteurization, and/or barrel maturation and racking.

Wine is a complex mixture of chemical compounds in a hydro-alcoholic solution with a pH around 4. The chemistry of wine and its resultant quality depend on achieving a balance between three aspects of the berries used to make the wine: their sugar content, acidity and the presence of secondary compounds. Vines store sugar in grapes through photosynthesis, and acids break down as grapes ripen. Secondary compounds are also stored in the course of the season. Anthocyanins give grapes a red color and protection against ultraviolet light. Tannins add bitterness and astringency which acts to defend vines against pests and grazing animals.

The role of yeast in winemaking is the most important element that distinguishes wine from fruit juice. In the absence of oxygen, yeast converts the sugars of the fruit into alcohol and carbon dioxide through the process of fermentation. The more sugars in the grapes, the higher the potential alcohol level of the wine if the yeast are allowed to carry out fermentation to dryness. Sometimes winemakers will stop fermentation early in order to leave some residual sugars and sweetness in the wine such as with dessert wines. This can be achieved by dropping fermentation temperatures to the point where the yeast are inactive, sterile filtering the wine to remove the yeast or fortification with brandy or neutral spirits to kill off the yeast cells. If fermentation is unintentionally stopped, such as when the yeasts become exhausted of available nutrients and the wine has not yet reached dryness, this is considered a stuck fermentation.

Wine preservatives are used to preserve the quality and shelf life of bottled wine without affecting its taste. Specifically, they are used to prevent oxidation and bacterial spoilage by inhibiting microbial activity.

The topic of sulfite food and beverage additives covers the application of sulfites in food chemistry. "Sulfite" is jargon that encompasses a variety of materials that are commonly used as preservatives or food additive in the production of diverse foods and beverages. Although sulfite salts are relatively nontoxic, their use has led to controversy, resulting in extensive regulations. Sulfites are a source of sulfur dioxide (SO2), a bactericide.