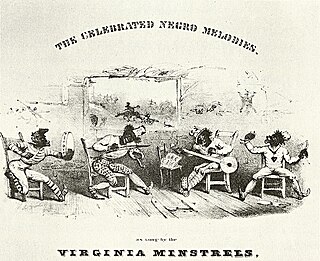

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of theater developed in the early 19th century. The shows were performed by mostly white actors wearing blackface makeup for the purpose of comically portraying racial stereotypes of African Americans. There were also some African-American performers and black-only minstrel groups that formed and toured. Minstrel shows stereotyped blacks as dimwitted, lazy, buffoonish, cowardly, superstitious, and happy-go-lucky. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people specifically of African descent.

Master Juba was an African-American dancer active in the 1840s. He was one of the first black performers in the United States to play onstage for white audiences and the only one of the era to tour with a white minstrel group. His real name was believed to be William Henry Lane, and he was also known as "Boz's Juba" following Dickens's graphic description of him in American Notes.

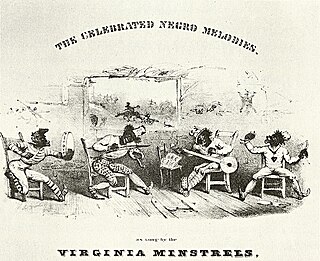

The Virginia Minstrels or Virginia Serenaders was a group of 19th-century American entertainers who helped invent the entertainment form known as the minstrel show. Led by Dan Emmett, the original lineup consisted of Emmett, Billy Whitlock, Dick Pelham, and Frank Brower.

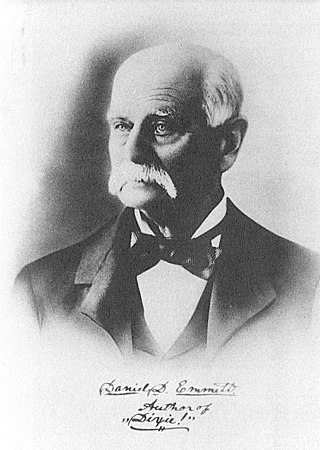

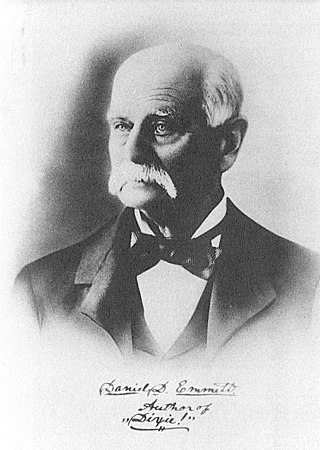

Daniel Decatur Emmett was an American composer, entertainer, and founder of the first troupe of the blackface minstrel tradition, the Virginia Minstrels. He is most remembered as the composer of the song "Dixie".

"Old Dan Tucker," also known as "Ole Dan Tucker," "Dan Tucker," and other variants, is an American popular song. Its origins remain obscure; the tune may have come from oral tradition, and the words may have been written by songwriter and performer Dan Emmett. The blackface troupe the Virginia Minstrels popularized "Old Dan Tucker" in 1843, and it quickly became a minstrel hit, behind only "Miss Lucy Long" and "Mary Blane" in popularity during the antebellum period. "Old Dan Tucker" entered the folk vernacular around the same time. Today it is a bluegrass and country music standard. It is no. 390 in the Roud Folk Song Index.

The Ethiopian Serenaders was an American blackface minstrel troupe successful in the 1840s and 1850s. Through various line-ups they were managed and directed by James A. Dumbolton (c.1808–?), and are sometimes mentioned as the Boston Minstrels, Dumbolton Company or Dumbolton's Serenaders.

Bryant's Minstrels was a blackface minstrel troupe that performed in the mid-19th century, primarily in New York City. The troupe was led by the O'Neill brothers from upstate New York, who took the stage name Bryant.

Mechanics' Hall was a meeting hall and theatre seating 2,500 people located at 472 Broadway in New York City, United States. It had a brown façade. Built by the Mechanics' Society for their monthly meetings in 1847, it was also used for banquets, luncheons, and speeches held by other groups.

Richard Ward "Dick" Pelham, born Richard Ward Pell, was an American blackface performer. He was born in New York City.

William M. Whitlock was an American blackface performer. He began his career in entertainment doing blackface banjo routines in circuses and dime shows, and by 1843 he was well known in New York City. He is best known for his role in forming the original minstrel show troupe, the Virginia Minstrels.

"Ole Bull and Old Dan Tucker" is a traditional American song. Several different versions are known, the earliest published in 1844 by the Boston-based Charles Keith company. The song's lyrics tell of the rivalry and contest of skill between Ole Bull and Dan Tucker. The song also satirizes the low pay earned by early minstrel performers: "Ole Bull come to town one day [and] got five hundred for to play."

Sanford's Opera Troupe was an American blackface minstrel troupe headed by Samuel S. Sanford (1821–1905). The troupe began in 1853 under the name Sanford's Minstrels. The name changed that same year to Sanford's Opera Troupe. The lineup changed in 1856 and again in 1857, when they disbanded.

"Miss Lucy Long", also known as "Lucy Long" as well as by other variants, is an American song that was popularized in the blackface minstrel show.

Francis Marion Brower was an American blackface performer active in the mid-19th century. Brower began performing blackface song-and-dance acts in circuses and variety shows when he was 13. He eventually introduced the bones to his act, helping to popularize it as a blackface instrument. Brower teamed with various other performers, forming his longest association with banjoist Dan Emmett beginning in 1841. Brower earned a reputation as a gifted dancer. In 1842, Brower and Emmett moved to New York City. They were out of work by January 1843, when they teamed up with Billy Whitlock and Richard Pelham to form the Virginia Minstrels. The group was the first to perform a full minstrel show as a complete evening's entertainment. Brower pioneered the role of the endman.

"Mary Blane", also known as "Mary Blain" and other variants, is an American song that was popularized in the blackface minstrel show. Several different versions are known, but all feature a male protagonist singing of his lover Mary Blane, her abduction, and eventual death. "Mary Blane" was by far the most popular female captivity song in antebellum minstrelsy.

John Diamond, aka Jack or Johnny, was an Irish-American dancer and blackface minstrel performer. Diamond entered show business at age 17 and soon came to the attention of circus promoter P. T. Barnum. In less than a year, Diamond and Barnum had a falling-out, and Diamond left to perform with other blackface performers. Diamond's dance style merged elements of English, Irish, and African dance. For the most part, he performed in blackface and sang popular minstrel tunes or accompanied a singer or instrumentalist. Diamond's movements emphasized lower-body movements and rapid footwork with little movement above the waist.

Luke Schoolcraft was an American minstrel music composer and performer. He appeared in numerous minstrel shows throughout the North after the American Civil War.

Julia Wildman Gould was an English-born singer and actress, who was the first woman to become a leading blackface performer in American minstrel shows.