Sir Phelim Roe O'Neill of Kinard was an Irish politician and soldier who started the Irish rebellion in Ulster on 23 October 1641. He joined the Irish Catholic Confederation in 1642 and fought in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms under his cousin, Owen Roe O'Neill, in the Confederate Ulster Army. After the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland O’Neill went into hiding but was captured, tried and executed in 1653.

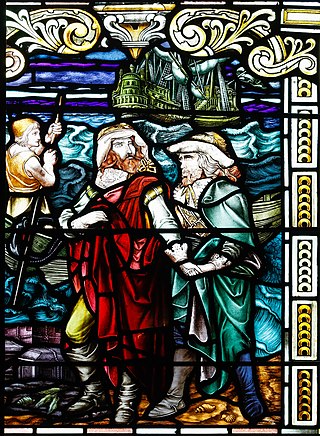

Sir Cahir O'Doherty was the last Gaelic Chief of the Name of Clan O'Doherty and Lord of Inishowen, in what is now County Donegal. O'Doherty was a noted loyalist during Tyrone's Rebellion and became known as the Queen's O'Doherty for his service on the Crown's side during the fighting.

McDevitt is an Irish surname, originating in County Donegal in the northwest part of Ireland. This family name is a member of the ancient Northern O’Néill group of clans who resided in the Ulster province of Ireland.

Events from the year 1608 in Ireland.

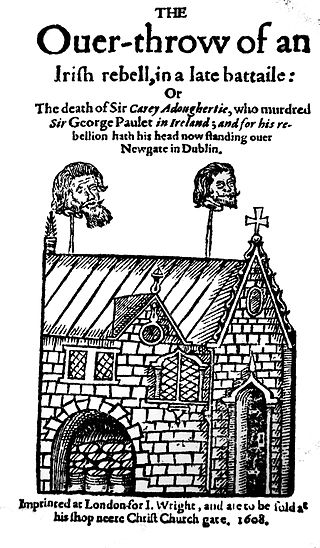

Sir George Paulet (1553–1608), also known as Pawlett, Pawlet, or Powlet, was an English soldier and administrator. He served as governor of Derry in Ireland. His arrogant and insolent behaviour caused O'Doherty's Rebellion in 1608. Paulet was killed by the rebels during the Burning of Derry.

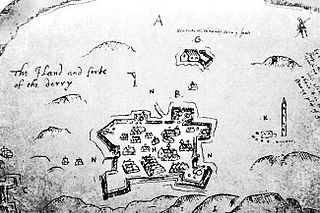

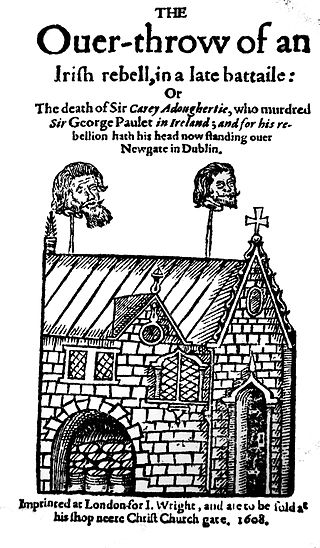

O'Doherty's Rebellion, also called O'Dogherty's Revolt, was an uprising against the Crown authorities in western Ulster, Ireland. Sir Cahir O'Doherty, lord of Inishowen, a Gaelic chieftain, had been a supporter of the Crown during the Nine Years' War (1593–1603), but angered at his treatment by Sir George Paulet, governor of Derry, he attacked and burned Derry in April 1608. O'Doherty was defeated and killed in the Battle of Kilmacrennan in July. The rebellion ended with the surrender of the last die-hards at the Siege of Tory Island later in the same year.

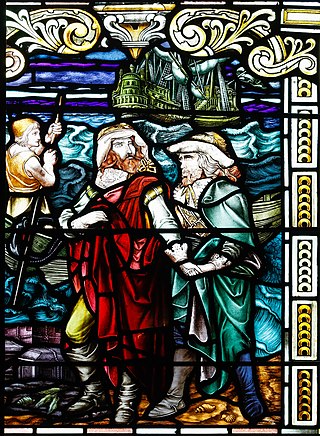

Henry Docwra, 1st Baron Docwra of Culmore was a leading English-born soldier and statesman in early seventeenth-century Ireland. He is often called "the founder of Derry", due to his role in establishing the city.

The Battle of Kilmacrennan was a skirmish fought near Kilmacrennan, County Donegal in 1608 during O'Doherty's Rebellion. Sir Cahir O'Doherty was a traditional supporter of the Crown whose treatment at the hands of local officials had led him to launch a rebellion in which he had seized the garrison town of Derry, killing his enemy George Paulet. O'Doherty raised local forces and possibly hoped to negotiate an agreement with the government as had been common with leaders of previous rebellions.

Sir Josias Bodley (1550-1618) was an English military engineer noted for his service in Ireland during the Nine Years' War. Following the end of the war he remained in Ireland where he oversaw the rebuilding of several major forts. In 1609 he was entrusted with the Bodley Survey which mapped out terrain for the Ulster Plantation.

Burt Castle is a ruined castle located close to Newtowncunningham and Burt, two villages in the east of County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland. Historically it was sometimes spelt as Birt Castle. It is also known by the name O'Doherty's Castle, and should not be mistaken for O'Doherty's Keep near Buncrana.

Henry Hart (1566-1637) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and landowner of the Elizabethan and early Stuart eras. He served in the Nine Years' War (1584-1603) and was later involved in the opening incident of O'Doherty's Rebellion in 1608. As a servitor he acquired an estate in County Donegal.

Phelim Reagh MacDavitt or Phelim Reagh MacDevitt was a Gaelic Irish warrior and landowner notable for his participation in the Nine Years War and later in O'Doherty's Rebellion in 1608. After playing a leading part in the Burning of Derry, he was captured and executed following the Battle of Kilmacrennan.

Hugh Boy MacDavitt was a Gaelic Irish warrior from Inishowen. He was the brother of Phelim Reagh MacDavitt and the foster brother of Sir Cahir O'Doherty. Cahir had a strong claim to succeed as chief of the O'Doherty's, the dominant clan on Inishowen. Because of this he was captured by Red Hugh O'Donnell, who supported a rival candidate. The MacDavitt brothers succeeded in rescuing him. They had previously sided with the rebels during the Nine Years War, with Hugh Boy making a failed attempt to capture Culmore Fort. They now switched to support the Crown and allied themselves to Sir Henry Docwra, the English Governor of Derry.

Sir Ralph Bingley (c.1570–1627) was a Welsh soldier who served and settled in Ireland.

The Burning of Dungannon took place in June 1602 when Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, abandoned and set fire to Dungannon, the traditional capital of the O'Neills. It marked the beginning of the final stage of Tyrone's Rebellion when the Earl became a fugitive, before his sudden reprieve the following year.

Sir Cormac MacBaron O'Neill (d.1613) was an Irish soldier and landowner of the Elizabethan and early Stuart eras. He was part of the O'Neill dynasty, one of the most prominent Gaelic families in Ireland.

Sir Arthur O'Neill or Sir Art O'Neill was an Irish soldier and landowner. He was part of the O'Neill dynasty, which was the most powerful Gaelic family in Ireland at the time. He was the son of Turlough Luineach O'Neill, the head of the O'Neill dynasty until 1595. He was the second son of Turlough, but his eldest brother Henry O'Neill died in 1578. At times he had a strained relationship with his father, and offered his support to Turlough's rival Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone. When Tyrone succeeded Turlough as head of the O'Neills and began Tyrone's Rebellion, Arthur offered tacit support to his distant cousin.

Sir Turlough McHenry O'Neill is known for having been killed together with his father, Henry, fighting for the crown in O'Doherty's Rebellion and for being the father of Sir Phelim O'Neill, who started the Irish Rebellion of 1641.

The Battle of Lifford was fought in County Donegal in October 1600, during the Nine Years' War in Ireland. A mixed Anglo-Irish force under Sir John Bolle and the Gaelic leaders Niall Garve O'Donnell and Sir Arthur O'Neill captured the strategic town of Lifford. A subsequent attempt to recapture it by forces led by Red Hugh O'Donnell failed.

Sir Richard Hansard was an English-born soldier who served and settled in Ireland during the Tudor and Stuart eras. He fought for the Crown during Tyrone's Rebellion, during which he was given command of the key town of Ballyshannon in County Donegal.