Leonardo Sciascia was an Italian writer, novelist, essayist, playwright, and politician. Some of his works have been made into films, including Porte Aperte, Cadaveri Eccellenti, Todo Modo and Il giorno della civetta. He is one of the greatest literary figures in the European literature of the 20th century.

The Fasci Siciliani, short for Fasci Siciliani dei Lavoratori, were a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration that arose in Sicily in the years between 1889 and 1894. The Fasci gained the support of the poorest and most exploited classes of the island by channeling their frustration and discontent into a coherent programme based on the establishment of new rights. Consisting of a jumble of traditionalist sentiment, religiosity, and socialist consciousness, the movement reached its apex in the summer of 1893, when new conditions were presented to the landowners and mine owners of Sicily concerning the renewal of sharecropping and rental contracts.

Caltavuturo is a town and comune in the Metropolitan City of Palermo, Sicily, Italy. The neighboring comunes are Polizzi Generosa, Scillato and Sclafani Bagni.

Giardinello is a comune (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Palermo in the Italian region Sicily, located about 20 kilometres (12 mi) west of Palermo. As of December 2010, it had a population of 2,260 and an area of 12.5 square kilometres (4.8 sq mi).

The Portella della Ginestra massacre refers to the killing of 11 people and 27 wounded during May Day celebrations in Sicily on 1 May 1947, in the municipality of Piana degli Albanesi. Those held responsible were the bandit and separatist leader Salvatore Giuliano and his gang, although their motives and intentions are still a matter of controversy.

Rosario Garibaldi Bosco was an Italian Republican-inspired socialist, politician and writer from Sicily. He was one of the leaders of the Fasci Siciliani, a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration in 1891-1894.

Giuseppe De Felice Giuffrida was an Italian socialist politician and journalist from Sicily. He is considered to be one of the founders of the Fasci Siciliani a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration. As the first socialist mayor of Catania in Sicily, from 1902 until 1914, he became the protagonist of a kind of municipal socialism.

Nicola Barbato was a Sicilian medical doctor, socialist, and politician. He was one of the national leaders of the Fasci Siciliani dei Lavoratori a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration in 1891–1894, and perhaps might have been the ablest among them according to the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm.

Napoleone Colajanni was an Italian writer, journalist, criminologist, socialist, and politician. In the 1880s, he abandoned republicanism for socialism, and became Italy's leading theoretical writer on the issue for a time. He has been called the father of Sicilian socialism. Due to the Italian Socialist Party's discourse of Marxist class struggle, he reverted in 1894 to his original republicanism and joined the Italian Republican Party. Colajanni was an ardent critic of the Lombrosian school in criminology. In 1890, he was elected in the national Chamber of Deputies and was re-elected in all subsequent parliaments until his death in September 1921.

Bernardino Verro was a Sicilian syndicalist and politician. He was involved in the Fasci Siciliani, a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration in 1891–1894, and became the first socialist mayor of Corleone in 1914. He was killed by the Mafia.

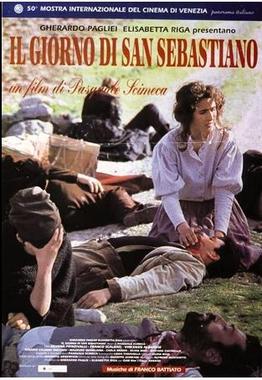

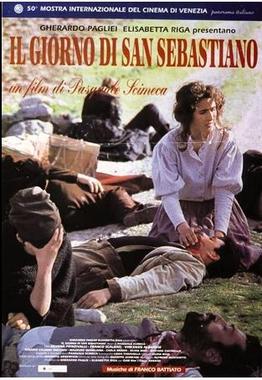

Pasquale Scimeca is an Italian film director and screenwriter.

Nicola Alongi, was a Sicilian socialist leader, involved in the Fasci Siciliani a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration in 1891–1894. He was killed by the Mafia.

Il giorno di San Sebastiano is an Italian film written and directed by Pasquale Scimeca. The film is based on true historical events, the Caltavuturo massacre that took place on January 20, 1893, in Caltavuturo in the Province of Palermo (Sicily), during the celebration of Saint Sebastian.

Events from the year 1893 in Italy.

The Giardinello massacre took place on December 10, 1893, in Giardinello in the Province of Palermo (Sicily) during the Fasci Siciliani uprising. Eleven people were killed and 12 seriously wounded after a rally that asked for the abolition of taxes on food and disbandment of the local field guards. The protestors carried the portrait of the King taken from the municipality and burned tax files.

The Lunigiana revolt took place in January 1894, in the stone and marble quarries of Massa and Carrara in the Lunigiana, the northernmost tip of Tuscany (Italy), in support of the Fasci Siciliani uprising on Sicily. After a state of siege had been proclaimed by the Crispi government, armed bands dispersed into the mountains pursued by troops. Hundreds of insurgents were arrested and tried by military tribunals.

Nicola Petrina was an Italian socialist and politician from Sicily. He was one of the national leaders of the Fasci Siciliani a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration from 1891 to 1894.

The Lercara Friddi massacre took place on Christmas-day 1893 in Lercara Friddi in the Province of Palermo (Sicily) during the Fasci Siciliani uprising. According to different sources either seven or eleven people were killed and many wounded.

Giacomo Montalto was an Italian Republican-inspired socialist, politician and lawyer. He was one of the leaders of the Fasci Siciliani, a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration in 1891–1894.