Related Research Articles

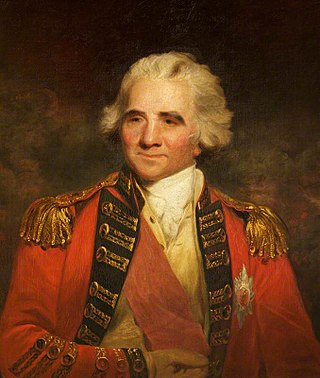

Lieutenant-General Sir Ralph Abercromby, was a Scottish soldier and politician. He rose to the rank of lieutenant-general in the British Army, was appointed Governor of Trinidad, served as Commander-in-Chief, Ireland, and was noted for his services during the French Revolutionary Wars, ultimately in the Egyptian campaign. His strategies are ranked amongst the most daring and brilliant exploits of the British army.

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda, was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture first fought and allied with Spanish forces against Saint-Domingue Royalists, then joined with Republican France, becoming Governor-General-for-life of Saint-Domingue, and lastly fought against Bonaparte's republican troops. As a revolutionary leader, Louverture displayed military and political acumen that helped transform the fledgling slave rebellion into a revolutionary movement. Along with Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Louverture is now known as one of the "Fathers of Haiti".

Saint-Domingue was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1697 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer specifically to the Spanish-held Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, now the Dominican Republic. The borders between the two were fluid and changed over time until they were finally solidified in the Dominican War of Independence in 1844.

Divisional-General Charles Victoire Emmanuel Leclerc was a French Army officer who served during the French Revolutionary Wars. He was the husband of Pauline Bonaparte, the sister of Napoleon. In 1801, Leclerc was sent to Saint-Domingue, where invasion forces under his command captured and deported Haitian leader Toussaint Louverture to France as part of an unsuccessful attempt to reassert French control over Saint-Domingue and reinstate slavery in the colony. Leclerc died of yellow fever during the campaign.

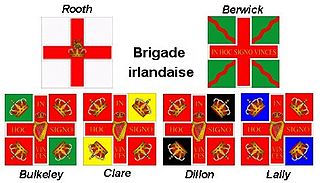

The Irish Brigade was a brigade in the French Royal Army composed of Irish exiles, led by Lord Mountcashel. It was formed in May 1690 when five Jacobite regiments were sent from Ireland to France in exchange for a larger force of French infantry who were sent to fight in the Williamite War in Ireland. The regiments comprising the Irish Brigade retained their special status as foreign units in the French Army until nationalised in 1791.

The Haitian Revolution was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known slave uprising in human history that led to the founding of a state which was both free from slavery and ruled by non-whites and former captives.

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax was a French abolitionist and Jacobin before joining the Girondist party, which emerged in 1791. During the French Revolution, he controlled 7,000 French troops in Saint-Domingue during part of the Haitian Revolution. His official title was Civil Commissioner. From September 1792, he and Polverel became the de facto rulers of Saint-Domingue's non-slave population. Because they were associated with Brissot’s party, they were put in accusation by the convention on July 16, 1793, but a ship to bring them back in France didn’t arrive in the colony until June 1794, and they arrived in France in the time of the downfall of Robespierre. They had a fair trial in 1795 and were acquitted of the charges the white colonists brought against them. Sonthonax believed that Saint-Domingue's whites were royalists or separatists, so he attacked the military power of the white settlers and by doing so alienated the colonial settlers from their government. Many gens de couleur asserted that they could form the military backbone of Saint-Domingue if they were given rights, but Sonthonax rejected this view as outdated in the wake of the August 1791 slave uprising. He believed that Saint-Domingue would need ex-slave soldiers among the ranks of the colonial army if it was to survive. In August 1793, he proclaimed freedom for all slaves in the north province. His critics allege that he was forced into ending slavery in order to maintain his own power.

George Biassou was an early leader of the 1791 slave rising in Saint-Domingue that began the Haitian Revolution. With Jean-François and Jeannot, he was prophesied by the vodou priest Dutty Boukman to lead the revolution.

Gabriel-Marie-Théodore-Joseph, comte d'Hédouville was a French soldier and diplomat.

The War of Knives, also known as the War of the South, was a civil war from June 1799 to July 1800 between the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture, a black ex-slave who controlled the north of Saint-Domingue, and his adversary André Rigaud, a mixed-race free person of color who controlled the south. Louverture and Rigaud fought over de facto control of the French colony of Saint-Domingue during the war. Their conflict followed the withdrawal of British forces from the colony earlier during the Haitian Revolution. The war resulted in Toussaint taking control of the entirety of Saint-Domingue, and Rigaud fleeing into exile.

The Irish Patriot Party was the name of a number of different political groupings in Ireland throughout the 18th century. They were primarily supportive of Whig concepts of personal liberty combined with an Irish identity that rejected full independence, but advocated strong self-government within the British Empire.

Dillon's Regiment was first raised in Ireland in 1688 by Theobald, 7th Viscount Dillon, for the Jacobite side in the Williamite War. He was then killed at the Battle of Aughrim in 1691.

Manuel Louis Jean Augustin Ernouf was a French general and colonial administrator of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. He demonstrated moderate abilities as a combat commander; his real strength lay in his organizational and logistical talents. He held several posts as chief-of-staff and in military administration.

Jean Baptiste Brunet was a French general of division in the French Revolutionary Army. He was responsible for the arrest of Toussaint Louverture. He was promoted to command a light infantry demi-brigade at the Fleurus in 1794. He led the unit in François Joseph Lefebvre's division in the 1795, 1796 and 1799 campaigns. He was the son of French general Gaspard Jean-Baptiste Brunet who was guillotined in 1793.

Macaya, was a Kongolese-born Haitian revolutionary military leader. Macaya was one of the first black rebel leaders in Saint-Domingue to ally himself with the French Republican commissioners Sonthonax and Polverel. He helped to lead forces that recaptured Cap-Français on behalf of the French Republicans.

The Indigenous Army, also known as the Army of Saint-Domingue was the name bestowed to the coalition of anti-slavery men and women who fought in the Haitian Revolution in Saint-Domingue. Encompassing both black slaves, maroons, and affranchis, the rebels were not officially titled the Armée indigène until January 1803, under the leadership of then-general Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Predated by insurrectionists such as François Mackandal, Vincent Ogé and Dutty Boukman, Toussaint Louverture, succeeded by Dessalines, led, organized, and consolidated the rebellion. The now full-fledged fighting force utilized its manpower advantage and strategic capacity to overwhelm French troops, ensuring the Haitian Revolution was the most successful of its kind.

Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux was a French general who was Governor of Saint-Domingue from 1793 to 1796 during the French Revolution. He ensured that the law that freed the slaves was enforced, and supported the black leader Toussaint Louverture, who later established the independent republic of Haiti. After the Bourbon Restoration he was Deputy for Saône-et-Loire from 1820 to 1823.

Charles Humbert Marie Vincent was a French general of the Revolution and the Empire.

The Law of 4 February 1794 was a decree of the French First Republic's National Convention which abolished slavery in the French colonial empire.

Haiti–United Kingdom relations refers to the international relations between Haiti and the United Kingdom. The Embassy of the United Kingdom in Port-au-Prince is accredited to Haiti, as is the British Embassy and Ambassador in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, while Haiti has an embassy in London and a consulates-general in Providenciales in Turks and Caicos Islands. While the two countries have maintained formal diplomatic recognition since 1859, the United Kingdom has maintained de facto diplomatic relations since Haiti's independence in 1804. The two countries maintain a maritime border between Haiti and the British-governed Turks and Caicos Islands.

References

- ↑ NFB (4 November 2015). "Ireland's Wars: The End Of The French Irish Brigade".

- ↑ Nini Rodgers. "The Irish in the Caribbean 1641-1837: An Overview". Society of Irish Latin American Studies.

- ↑ fournationshistory (2 May 2016). "'Loyalty and Zeal': the Catholic Irish Brigade in the British service, 1793-98".