Ur was an important Sumerian city-state in ancient Mesopotamia, located at the site of modern Tell el-Muqayyar in south Iraq's Dhi Qar Governorate. Although Ur was once a coastal city near the mouth of the Euphrates on the Persian Gulf, the coastline has shifted and the city is now well inland, on the south bank of the Euphrates, 16 km (10 mi) from Nasiriyah in modern-day Iraq. The city dates from the Ubaid period circa 3800 BC, and is recorded in written history as a city-state from the 26th century BC, its first recorded king being King Tuttues.

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be conducted over a few weeks to several years.

Puabi, also called Shubad or Shudi-Ad due to a misinterpretation by Sir Charles Leonard Woolley, was an important woman in the Sumerian city of Ur, during the First Dynasty of Ur. Commonly labeled as a "queen", her status is somewhat in dispute, although several cylinder seals in her tomb, labeled grave PG 800 at the Royal Cemetery at Ur, identify her by the title "nin" or "eresh", a Sumerian word denoting a queen or a priestess. Puabi's seal does not place her in relation to any king or husband, possibly indicating that she ruled in her own right. It has been suggested that she was the second wife of king Meskalamdug. The fact that Puabi, herself a Semitic Akkadian, was an important figure among Sumerians, indicates a high degree of cultural exchange and influence among the ancient Sumerians and their Semitic neighbors. Although little is known about Puabi's life, the discovery of Puabi's tomb and its death pit reveals important information as well as raises questions about Mesopotamian society and culture.

The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki is a museum in Thessaloniki, Central Macedonia, Greece. It holds and interprets artifacts from the Prehistoric, Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods, mostly from the city of Thessaloniki but also from the region of Macedonia in general.

Herodion, Herodium (Latin), or Jabal al-Fureidis is an ancient fortress located 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) south of Jerusalem and 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) southeast of Bethlehem. It is located between the villages of Beit Ta'mir, Za'atara and Jannatah. It is identified with the site of Herodium, built by King of Judea Herod the Great built between 23 and 15 BCE. Herodium is 758 meters (2,487 ft) above sea level.

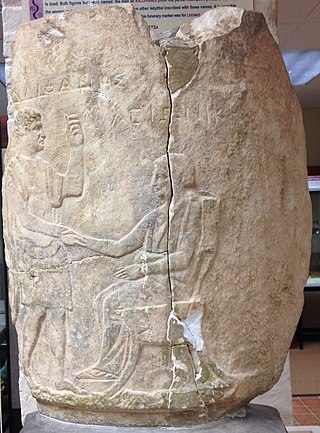

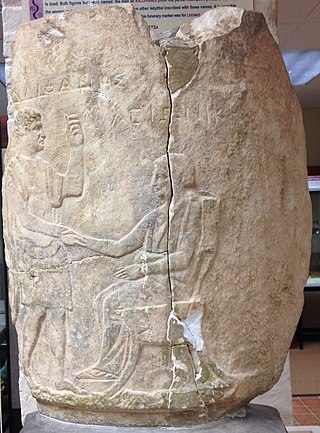

The Standard of Ur is a Sumerian artifact of the 3rd millennium BC that is now in the collection of the British Museum. It comprises a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimetres (8.50 in) wide by 49.53 centimetres (19.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli. It comes from the ancient city of Ur. It dates to the First Dynasty of Ur during the Early Dynastic period and is around 4,600 years old. The standard was probably constructed in the form of a hollow wooden box with scenes of war and peace represented on each side through elaborately inlaid mosaics. Although interpreted as a standard by its discoverer, its original purpose remains enigmatic. It was found in a royal tomb in Ur in the 1920s next to the skeleton of a ritually sacrificed man who may have been its bearer.

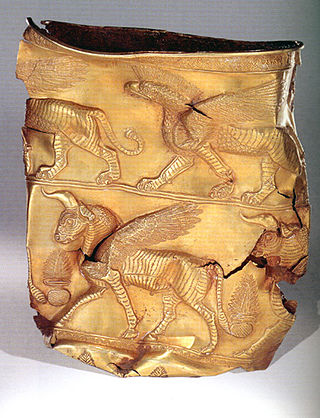

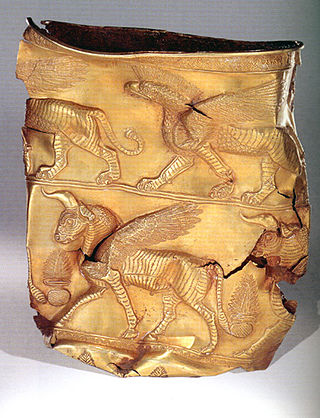

Marlik is an ancient site near Roudbar in Gilan, in northern Iran. Marlik, also known as Cheragh-Ali Tepe is located in the valley of Gohar Rud, a tributary of Sepid Rud in Gilan Province in Northern Iran, Marlik. Marlik is the site of a royal cemetery, and artifacts found at this site date back to 3,000 years ago. Some of the artifacts contain amazing workmanship with gold. Marlik is named after the Amard people.

Meskalamdug was an early Sumerian ruler of the First Dynasty of Ur in the 26th century BCE. He does not appear in the Sumerian King List, but is known from a royal cylinder seal found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, a royal bead inscription found in Mari, both mentioning him as King, and possibly his tomb, grave PG 755 at the Royal Cemetery at Ur.

Malagana, also known as the Malagana Treasure is an archaeological site of Colombia named after a sugarcane estate where it was accidentally discovered in 1992. During the few days after its discovery, the place was subject to a large scale looting with a rough estimate of 4 tons of pre-Columbian artifacts illegally removed from the burial mounds. A rescue archaeological mission was sent by the National Institute of Anthropology and History (ICANH), led by archaeologist Marianne Cardale de Schrimpff. Archaeological excavations at the site established a previously unknown cultural complex, designated as Malagana-Sonsoid, that dates between 300 BC to 300 AD.

An archaeology museum is a museum that specializes in the display of archaeological artifacts.

Mucking is an archaeological site near the village of Mucking in southern Essex. The site contains remains dating from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages—a period of some 3,000 years—and the Bronze Age and Anglo-Saxon features are particularly notable.

The National Museum of Archaeology is a Maltese museum in Valletta, with artefacts from prehistory, Phoenician times and a notable numismatic collection. It is managed by Heritage Malta.

The Domus Romana, stylized as the Domvs Romana, is a ruined Roman-era house located on the boundary between Mdina and Rabat, Malta. It was built in the 1st century BC as an aristocratic town house (domus) within the Roman city of Melite. In the 11th century, a Muslim cemetery was established on the remains of the domus.

The Museum of Classical Archaeology is the teaching collection of the Department of Classics, Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

The Royal Cemetery at Ur is an archaeological site in modern-day Dhi Qar Governorate in southern Iraq. The initial excavations at Ur took place between 1922 and 1934 under the direction of Leonard Woolley in association with the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.

Aydın Archaeological Museum is in Aydın, western Turkey. Established in 1959, it contains numerous statues, tombs, columns and stone carvings from the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Seljuk and Ottoman periods, unearthed in ancient cities such as Alinda, Alabanda, Amyzon, Harpasa, Magnesia on the Maeander, Mastaura, Myus, Nisa, Orthosia, Piginda, Pygela and Tralleis. The museum also has a section devoted to ancient coin finds.

Sinop Archaeological Museum, or Sinop Museum, is a national museum in Sinop, Turkey, exhibiting archaeological artifacts found in and around the city.

Holly Pittman is a Near Eastern art historian and archaeologist, and an expert in Near Eastern glyptic art. She is the Bok Family Professor in the Humanities and a Professor in the History of Art Department of the University of Pennsylvania and serves as a curator in the Near East Section of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Before joining the University of Pennsylvania, she was a curator of Ancient Near Eastern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1974 to 1989. Since 1972, she has conducted archaeological excavations throughout the Middle East, including projects in Syria, Turkey, Cyprus, Iran, and Iraq. In 2019 she began directing new excavations at the site of Lagash in southern Iraq.

Başur Höyük in Turkey's south-eastern Siirt Province is the location of a 5,000-year-old Bronze Age burial site. The 820-foot by 492-foot burial mound in a valley of the upper Tigris River was excavated in the years up to 2018, by Brenna Hassett of the Natural History Museum in London, and Haluk Sağlamtimur of Ege University in Turkey. The tomb contained the remains of two 12-year-old children, and the remains of an adult which may have been reburied. The remains of eight other people aged 11 to 20 were found buried outside the tomb. These remains were carbon-dated to between 3100 and 2800 BCE, and at least some of the people are believed to have been sacrificed.

Ur-Pabilsag was an early ruler of the First Dynasty of Ur in the 26th century BCE. He does not appear in the Sumerian King List, but is known from an inscription fragment found in Ur, bearing the title "Ur-Pabilsag, king of Ur". It has been suggested that his tomb is at the Royal Cemetery at Ur. He may have died around 2550 BCE.