Neorealism or structural realism is a theory of international relations that emphasizes the role of power politics in international relations, sees competition and conflict as enduring features and sees limited potential for cooperation. The anarchic state of the international system means that states cannot be certain of other states' intentions and their security, thus prompting them to engage in power politics.

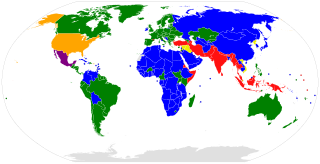

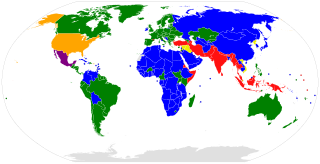

The Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, more commonly referred to as the Fourth Geneva Convention and abbreviated as GCIV, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. It was adopted in August 1949, and came into force in October 1950. While the first three conventions dealt with combatants, the Fourth Geneva Convention was the first to deal with humanitarian protections for civilians in a war zone. There are currently 196 countries party to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, including this and the other three treaties.

Combatant is the legal status of a person entitled to directly participate in hostilities during an armed conflict, and may be intentionally targeted by an adverse party for their participation in the armed conflict. Combatants are not afforded immunity from being directly targeted in situations of armed conflict and can be attacked regardless of the specific circumstances simply due to their status, so as to deprive their side of their support.

A casus belli is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A casus belli involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a casus foederis involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one bound by a mutual defense pact. Either may be considered an act of war. A declaration of war usually contains a description of the casus belli that has led the party in question to declare war on another party.

An ultimatum is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance. An ultimatum is generally the final demand in a series of requests. As such, the time allotted is usually short, and the request is understood not to be open to further negotiation. The threat which backs up the ultimatum can vary depending on the demand in question and on the other circumstances.

A military alliance is a formal agreement between nations that specifies mutual obligations regarding national security. In the event a nation is attacked, members of the alliance are often obligated to come to their defense regardless if attacked directly. Military alliances can be classified into defense pacts, non-aggression pacts, and ententes. Alliances may be covert or public.

Power politics is a theory of power in international relations which contends that distributions of power and national interests, or changes to those distributions, are fundamental causes of war and of system stability.

In international relations, the concept of balancing derives from the balance of power theory, the most influential theory from the realist school of thought, which assumes that a formation of hegemony in a multistate system is unattainable since hegemony is perceived as a threat by other states, causing them to engage in balancing against a potential hegemon.

In international relations, the security dilemma is when the increase in one state's security leads other states to fear for their own security. Consequently, security-increasing measures can lead to tensions, escalation or conflict with one or more other parties, producing an outcome which no party truly desires; a political instance of the prisoner's dilemma.

Hegemonic stability theory (HST) is a theory of international relations, rooted in research from the fields of political science, economics, and history. HST indicates that the international system is more likely to remain stable when a single state is the dominant world power, or hegemon. Thus, the end of hegemony diminishes the stability of the international system. As evidence for the stability of hegemony, proponents of HST frequently point to the Pax Britannica and Pax Americana, as well as the instability prior to World War I and the instability of the interwar period.

Collective security is a multi-lateral security arrangement between states in which each state in the institution accepts that an attack on one state is the concern of all and merits a collective response to threats by all. Collective security was a key principle underpinning the League of Nations and the United Nations. Collective security is more ambitious than systems of alliance security or collective defense in that it seeks to encompass the totality of states within a region or indeed globally.

Realism, a school of thought in international relations theory, is a theoretical framework that views world politics as an enduring competition among self-interested states vying for power and positioning within an anarchic global system devoid of a centralized authority. It centers on states as rational primary actors navigating a system shaped by power politics, national interest, and a pursuit of security and self-preservation.

Polarity in international relations is any of the various ways in which power is distributed within the international system. It describes the nature of the international system at any given period of time. One generally distinguishes three types of systems: unipolarity, bipolarity, and multipolarity for three or more centers of power. The type of system is completely dependent on the distribution of power and influence of states in a region or globally.

Buck passing, or passing the buck, or sometimes (playing) the blame game, is the act of attributing to another person or group one's own responsibility. It is often used to refer to a strategy in power politics whereby a state tries to get another state to deter or fight an aggressor state while it remains on the sidelines.

Offensive realism is a structural theory in international relations that belongs to the neorealist school of thought and was put forward by the political scholar John Mearsheimer in response to defensive realism. Offensive realism holds that the anarchic nature of the international system is responsible for the promotion of aggressive state behavior in international politics. The theory fundamentally differs from defensive realism by depicting great powers as power-maximizing revisionists privileging buck-passing and self-promotion over balancing strategies in their consistent aim to dominate the international system. The theory brings important alternative contributions for the study and understanding of international relations but remains the subject of criticism.

The balance of power theory in international relations suggests that states may secure their survival by preventing any one state from gaining enough military power to dominate all others. If one state becomes much stronger, the theory predicts it will take advantage of its weaker neighbors, thereby driving them to unite in a defensive coalition. Some realists maintain that a balance-of-power system is more stable than one with a dominant state, as aggression is unprofitable when there is equilibrium of power between rival coalitions.

Defensive neorealism is a structural theory in international relations that is derived from the school of neorealism. The theory finds its foundation in the political scientist Kenneth Waltz's Theory of International Politics in which Waltz argues that the anarchical structure of the international system encourages states to maintain moderate and reserved policies to attain national security. In contrast, offensive realism assumes that states seek to maximize their power and influence to achieve security through domination and hegemony. Defensive neorealism asserts that aggressive expansion as promoted by offensive neorealists upsets the tendency of states to conform to the balance of power theory, thereby decreasing the primary objective of the state, which they argue to be the ensuring of its security. Defensive realism denies neither the reality of interstate conflict or that incentives for state expansion exist, but it contends that those incentives are sporadic, rather than endemic. Defensive neorealism points towards "structural modifiers," such as the security dilemma and geography, and elite beliefs and perceptions to explain the outbreak of conflict.

The military doctrine of Russia is a strategic planning document of the Russian Federation, representing a system of official state-adopted views on preparation and usage of the Russian Armed Forces. The most recent revision of the military doctrine was approved in 2014.

This is a list of terms related to the study of international relations. Many of these terms are also used in the study of sociology and game theory.

Thomas J. Christensen is an American political scientist. He is the James T. Shotwell Professor of International Relations at the School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University.