The flowering plants, also known as Angiospermae, or Magnoliophyta, are the most diverse group of land plants, with 64 orders, 416 families, approximately 13,000 known genera and 300,000 known species. Like gymnosperms, angiosperms are seed-producing plants. They are distinguished from gymnosperms by characteristics including flowers, endosperm within the seeds, and the production of fruits that contain the seeds. Etymologically, angiosperm means a plant that produces seeds within an enclosure; in other words, a fruiting plant. The term comes from the Greek words angeion and sperma ("seed").

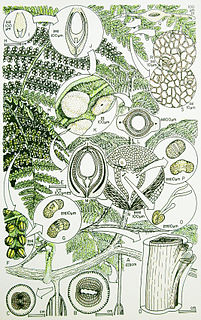

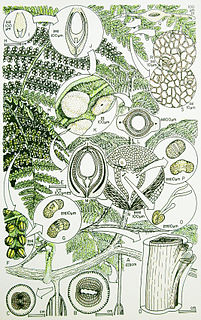

A seed is an embryonic plant enclosed in a protective outer covering. The formation of the seed is part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, including the gymnosperm and angiosperm plants.

An archegonium, from the ancient Greek ἀρχή ("beginning") and γόνος ("offspring"), is a multicellular structure or organ of the gametophyte phase of certain plants, producing and containing the ovum or female gamete. The corresponding male organ is called the antheridium. The archegonium has a long neck canal or venter and a swollen base. Archegonia are typically located on the surface of the plant thallus, although in the hornworts they are embedded.

Allan Cunningham was an English botanist and explorer, primarily known for his travels in Australia to collect plants.

The gymnosperms, also known as Acrogymnospermae, are a group of seed-producing plants that includes conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and gnetophytes. The term "gymnosperm" comes from the composite word in Greek: γυμνόσπερμος, literally meaning "naked seeds". The name is based on the unenclosed condition of their seeds. The non-encased condition of their seeds contrasts with the seeds and ovules of flowering plants (angiosperms), which are enclosed within an ovary. Gymnosperm seeds develop either on the surface of scales or leaves, which are often modified to form cones, or solitary as in yew, Torreya, Ginkgo.

Robert Brown FRSE FRS FLS MWS was a Scottish botanist and paleobotanist who made important contributions to botany largely through his pioneering use of the microscope. His contributions include one of the earliest detailed descriptions of the cell nucleus and cytoplasmic streaming; the observation of Brownian motion; early work on plant pollination and fertilisation, including being the first to recognise the fundamental difference between gymnosperms and angiosperms; and some of the earliest studies in palynology. He also made numerous contributions to plant taxonomy, notably erecting a number of plant families that are still accepted today; and numerous Australian plant genera and species, the fruit of his exploration of that continent with Matthew Flinders.

A sporophyte is the diploid multicellular stage in the life cycle of a plant or alga. It develops from the zygote produced when a haploid egg cell is fertilized by a haploid sperm and each sporophyte cell therefore has a double set of chromosomes, one set from each parent. All land plants, and most multicellular algae, have life cycles in which a multicellular diploid sporophyte phase alternates with a multicellular haploid gametophyte phase. In the seed plants, the largest groups of which are the gymnosperms and flowering plants (angiosperms), the sporophyte phase is more prominent than the gametophyte, and is the familiar green plant with its roots, stem, leaves and cones or flowers. In flowering plants the gametophytes are very reduced in size, and are represented by the germinated pollen and the embryo sac.

Adolphe-Théodore Brongniart FRS FRSE FGS was a French botanist. He was the son of the geologist Alexandre Brongniart and grandson of the architect, Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart. Brongniart's pioneering work on the relationships between extinct and existing plants has earned him the title of father of paleobotany. His major work on plant fossils was his Histoire des végétaux fossiles (1828–37). He wrote his dissertation on the Buckthorn family (Rhamnaceae), an extant family of flowering plants, and worked at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris until his death. In 1851, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. This botanist is denoted by the author abbreviation Brongn. when citing a botanical name.

In seed plants, the ovule is the structure that gives rise to and contains the female reproductive cells. It consists of three parts: The integument, forming its outer layer, the nucellus, and the female gametophyte in its center. The female gametophyte — specifically termed a megagametophyte— is also called the embryo sac in angiosperms. The megagametophyte produces an egg cell for the purpose of fertilization.

Cephalotus is a genus which contains one species, Cephalotus follicularis the Albany pitcher plant, a small carnivorous pitcher plant. The pit-fall traps of the modified leaves have inspired the common names for this plant, which include 'Albany pitcher plant", "Western Australian pitcher plant", "Australian pitcher plant", or "fly-catcher plant."

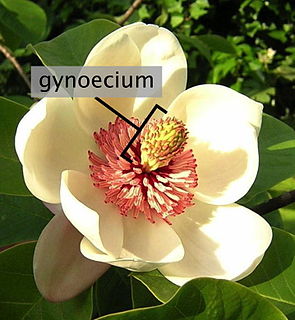

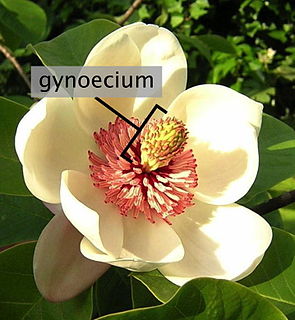

Gynoecium is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl of a flower; it consists of pistils and is typically surrounded by the pollen-producing reproductive organs, the stamens, collectively called the androecium. The gynoecium is often referred to as the "female" portion of the flower, although rather than directly producing female gametes, the gynoecium produces megaspores, each of which develops into a female gametophyte which then produces egg cells.

Kingia is a genus consisting of a single species, Kingia australis, and belongs to the plant family Dasypogonaceae. It has a thick pseudo-trunk consisting of accumulated leaf-bases, with a cluster of long, slender leaves on top. The trunk is usually unbranched, but can branch if the growing tip is damaged. Flowers occur in egg-shaped clusters on the ends of up to 100 long curved stems. Kingia grows extremely slowly, the trunk increasing in height by about 1½ centimetres per year. It can live for centuries, however, so can attain a substantial height; 400-year-old plants with a height of six metres are not unusual.

Brunonia australis, commonly known as the blue pincushion or native cornflower, is a perennial or annual herb that grows widely across Australia. It is found in woodlands, open forest and sand plains. In Cronquist's classification scheme it was the sole member of the monogeneric plant family Brunoniaceae. The APG II system moved it into Goodeniaceae, with which it shares the stylar pollen-cup, or indusium, a character confined to these taxa. Brunonia is unique among Goodeniaceae in its radially symmetric flowers, the superior ovary and the absence of endosperm in the seeds.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to botany:

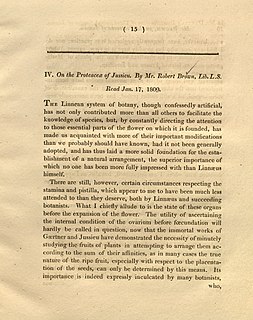

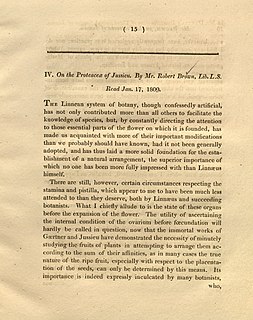

On the natural order of plants called Proteaceae, also published as "On the Proteaceae of Jussieu", was a paper written by Robert Brown on the taxonomy of the plant family Proteaceae. It was read to the Linnean Society of London in the first quarter of 1809, and published in March 1810. It is significant for its contribution to the systematics of Proteaceae, and to the floristics of Australia, and also for its application of palynology to systematics.

The Caytoniales are an extinct order of seed plants known from fossils collected throughout the Mesozoic Era, specifically in the late Triassic to Maastrichtian period, around 250 to 70 million years ago. They are regarded as seed ferns because they are seed-bearing plants with fern-like leaves. Although at one time considered angiosperms because of their berry-like cupules, that hypothesis was later disproven. Nevertheless, some authorities consider them likely ancestors of angiosperms, whereas others consider angiosperms more likely derived from Glossopteridales. The origin of angiosperms remains an intriguing puzzle.

General remarks, geographical and systematical, on the botany of Terra Australis is an 1814 paper written by Robert Brown on the botany of Australia. It is significant as an early treatment of the biogeography and floristics of the flora of Australia; for its contributions to plant systematics, including the erection of eleven currently accepted families; and for its presentation of a number of important observations on flower morphology.

The Medullosales is an order of pteridospermous seed plants characterised by large ovules with circular cross-section, with a vascularised nucellus, complex pollen-organs, stems and rachides with a dissected stele, and frond-like leaves. Their nearest still-living relatives are the cycads.

The Lyginopteridales were the archetypal pteridosperms: They were the first plant fossils to be described as pteridosperms and, thus, the group on which the concept of pteridosperms was first developed; they are the stratigraphically oldest-known pteridosperms, occurring first in late Devonian strata; and they have the most primitive features, most notably in the structure of their ovules. They probably evolved from a group of Late Devonian progymnosperms known as the Aneurophytales, which had large, compound frond-like leaves. The Lyginopteridales became the most abundant group of pteridosperms during Mississippian times, and included both trees and smaller plants. During early and most of middle Pennsylvanian times the Medullosales took over as the more important of the larger pteridosperms but the Lyginopteridales continued to flourish as climbing (lianescent) and scrambling plants. However, later in Middle Pennsylvanian times the Lyginopteridales went into serious decline, probably being out-competed by the Callistophytales that occupied similar ecological niches but had more sophisticated reproductive strategies. A few species continued into Late Pennsylvanian times, and in China persisted into Early Permian (Asselian) times, but then became extinct. Most evidence of the Lyginopteridales suggests that they grew in tropical latitudes of the time, in North America, Europe and China.

The Callistophytaceae was a family of seed ferns (pteridosperms) from the Carboniferous and Permian periods. They first appeared in late Middle Pennsylvanian (Moscovian) times, 306.5–311.7 million years ago (Ma) in the tropical coal forests of Euramerica, and became an important component of Late Pennsylvanian vegetation of clastic soils and some peat soils. The best known callistophyte was documented from Late Pennsylvanian coal ball petrifactions in North America.