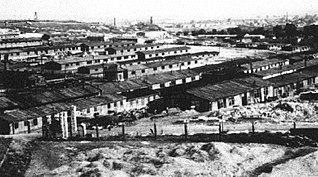

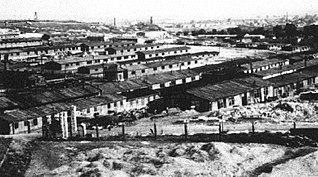

Auschwitz concentration camp was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschwitz I, the main camp (Stammlager) in Oświęcim; Auschwitz II-Birkenau, a concentration and extermination camp with gas chambers; Auschwitz III-Monowitz, a labour camp for the chemical conglomerate IG Farben; and dozens of subcamps. The camps became a major site of the Nazis' Final Solution to the Jewish question.

I. G. Farbenindustrie AG, commonly known as IG Farben, was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. It was formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies: Agfa, BASF, Bayer, Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron, Hoechst, and Weiler-ter-Meer. It was seized by the Allies after World War II and split into its constituent companies; parts in East Germany were nationalized.

The German camps in occupied Poland during World War II were built by the Nazis between 1939 and 1945 throughout the territory of the Polish Republic, both in the areas annexed in 1939, and in the General Government formed by Nazi Germany in the central part of the country (see map). After the 1941 German attack on the Soviet Union, a much greater system of camps was established, including the world's only industrial extermination camps constructed specifically to carry out the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question".

The United States of America vs. Carl Krauch, et al., also known as the IG Farben Trial, was the sixth of the twelve trials for war crimes the U.S. authorities held in their occupation zone in Germany (Nuremberg) after the end of World War II. IG Farben was the private German chemicals company allied with the Nazis that manufactured the Zyklon B gas used to commit genocide against millions of European Jews in the Holocaust.

Hans Frankenthal was a German Jew who was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp in occupied Poland in 1943. Having survived the Holocaust along with his brother Ernst, Frankenthal returned to his home in Germany where he experienced the common disbelief and denial of Nazi war crimes.

Monowitz was a Nazi concentration camp and labor camp (Arbeitslager) run by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland from 1942–1945, during World War II and the Holocaust. For most of its existence, Monowitz was a subcamp of the Auschwitz concentration camp; from November 1943 it and other Nazi subcamps in the area were jointly known as "Auschwitz III-subcamps". In November 1944 the Germans renamed it Monowitz concentration camp, after the village of Monowice where it was built, in the annexed portion of Poland. SS Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Heinrich Schwarz was commandant from November 1943 to January 1945.

Norbert Wollheim was a chartered accountant, tax advisor, previously a board member of the Central Council of Jews in Germany and a functionary of other Jewish organisations.

Stalag VIII-B was a German Army prisoner-of-war camp during World War II, later renumbered Stalag-344, located near the village of Lamsdorf in Silesia. The camp initially occupied barracks built to house British and French prisoners in World War I. At this same location there had been a prisoner camp during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

Stalag VIII-D was a German World War II prisoner-of-war camp (Stammlager) located at the outskirts of Teschen,. It was built in March 1941 on the grounds of a former Czech barracks. It was later known as Stalag VIII-B.

Arbeitslager is a German language word which means labor camp. Under Nazism, the German government used forced labor extensively, starting in the 1930s but most especially during World War II. Another term was Zwangsarbeitslager.

The Fürstengrube subcamp was organized in the summer of 1943 at the Fürstengrube hard coal mine in the town of Wesoła (Wessolla) near Myslowice (Myslowitz), approximately 30 kilometers (19 mi) from Auschwitz concentration camp. The mine, which IG Farbenindustrie AG acquired in February 1941, was to supply hard coal for the IG Farben factory being built in Auschwitz. Besides the old Fürstengrube mine, called the Altanlage, a new mine (Fürstengrube-Neuanlage) had been designed and construction had begun; it was to provide for greater coal output in the future. Coal production at the new mine was anticipated to start in late 1943, so construction was treated as very urgent; however, that plan proved to be unfeasible.

Fritz ter Meer was a German chemist, Bayer board chairman, Nazi Party member and war criminal.

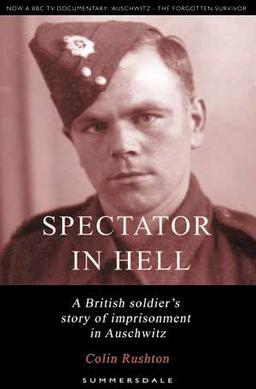

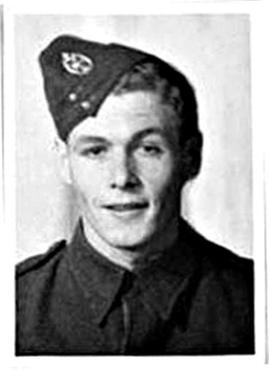

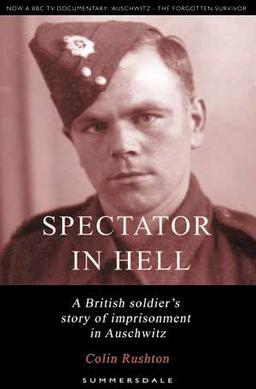

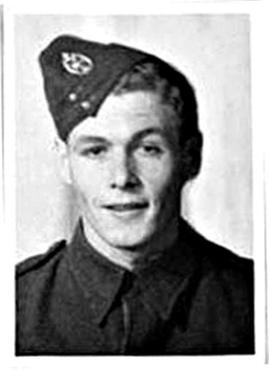

Arthur Dodd served in the British Army during World War II. After being captured at Tobruk, he became a Prisoner of War and was imprisoned at E715, an Allied POW camp attached to Auschwitz III (Monowitz), a sub-camp of the notorious Auschwitz.

Denis Avey was a British veteran of the Second World War who was held as a prisoner of war at E715, a subcamp of Auschwitz. While there he saved the life of a Jewish prisoner, Ernst Lobethal, by smuggling cigarettes to him. For that he was made a British Hero of the Holocaust in 2010.

Otto Ambros was a German chemist and Nazi war criminal. He is known for his wartime work on synthetic rubber and nerve agents. After the war he was tried at Nuremberg and convicted of crimes against humanity for his use of slave labor from the Auschwitz III–Monowitz concentration camp. In 1948 he was sentenced to 8 years' imprisonment, but released early in 1951 for good behavior.

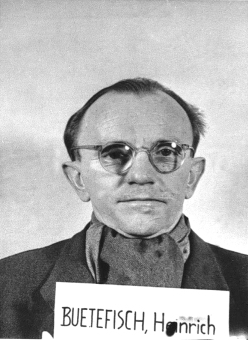

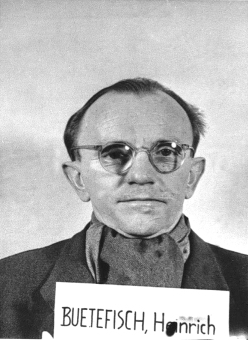

Heinrich Bütefisch was a German chemist, manager at IG Farben, and Nazi war criminal. He was an Obersturmbannführer in the SS.

Friedrich Karl Hermann Entress was a German camp doctor in various concentration and extermination camps during the Second World War. He conducted human medical experimentation at Auschwitz and introduced the procedure there of injecting lethal doses of phenol directly into the hearts of prisoners. He was captured by the Allies in 1945, sentenced to death at the Mauthausen-Gusen camp trials, and executed in 1947.

Karel Sperber OBE (1910–1957) was a Jewish Czechoslovak surgeon who travelled to England after the Nazi invasion of his country, but unable to practice medicine because he was an alien, took a job as a ship's doctor instead and was captured by Axis forces when his ship was sunk by the Germans.

The Wollheim Memorial is a Holocaust memorial site in Frankfurt am Main.

Private sector participation in Nazi crimes was extensive and included widespread use of forced labor in Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe, confiscation of property from Jews and other victims by banks and insurance companies, and the transportation of people to Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps by rail. After the war, companies sought to downplay their participation in crimes and claimed that they were also victims of Nazi totalitarianism. However, the role of the private sector in Nazi Germany has been described as an example of state-corporate crime.