Michel de l'Hôpital was a French lawyer, diplomat and chancellor during the latter Italian Wars and the early French Wars of Religion. The son of a doctor in the service of Constable Bourbon he spent his early life exiled from France at Bourbon's and then the emperors court. When his father entered the service of the House of Lorraine, he entered the patronage network of Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine. Through his marriage to Marie Morin, he acquired a seat in the Paris Parlement. In this capacity he drew up the charges for the king, concerning the defenders of Boulogne who surrendered the city in 1544, before taking a role as a diplomat to the Council of Trent in 1547. The following year he assisted Anne d'Este in the details of her inheritance to ensure she could marry Francis, Duke of Guise.

Antoine de Bourbon, roi de Navarre was the King of Navarre through his marriage to Queen Jeanne III, from 1555 until his death. He was the first monarch of the House of Bourbon, of which he was head from 1537. Despite being first prince of the blood, Antoine lacked political influence and was dominated by king Henry II's favourites, the Montmorency and Guise families. When Henri died in 1559, Antoine found himself sidelined in the Guise-dominated government, and then compromised by his brother's treason. When Francis in turn died he returned to the centre of politics, becoming Lieutenant-General of France and leading the army of the crown in the first of the French Wars of Religion. He died of wounds sustained during the Siege of Rouen. He was the father of Henry IV of France.

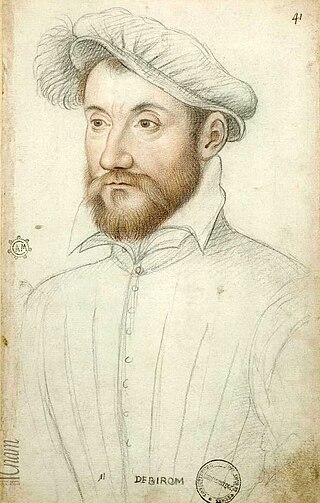

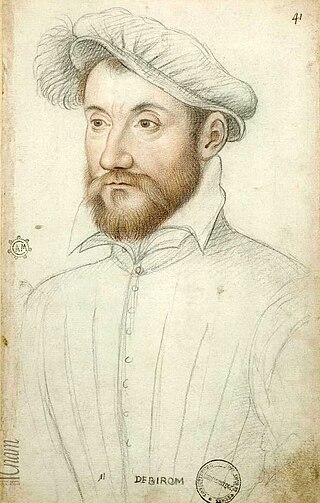

Armand de Gontaut, Baron of Biron was a soldier, diplomat and Marshal of France. Beginning his service during the Italian Wars, Biron served in Italy under Marshal Brissac and Guise in 1557 before rising to command his own cavalry regiment. Returning to France with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis he took up his duties in Guyenne, where he observed the deteriorating religious situation that was soon to devolve into the French Wars of Religion. He fought at the Battle of Dreux in the first civil war. In the peace that followed he attempted to enforce the terms on the rebellious governorship of Provence.

The Edict of Saint-Germain, also known as the Edict of January, was a landmark decree of tolerance promulgated by the regent of France, Catherine de' Medici, in January 1562. The edict provided limited tolerance to the Protestant Huguenots in the Catholic realm, though with counterweighing restrictions on their behaviour. The act represented the culmination of several years of slowly liberalising edicts which had begun with the 1560 Edict of Amboise. After two months the Paris Parlement would be compelled to register it by the rapidly deteriorating situation in the capital. The practical impact of the edict would be highly limited by the subsequent outbreak of the first French Wars of Religion but it would form the foundation for subsequent toleration edicts as the Edict of Nantes of 1598.

Jacques de Savoie, duc de Nemours was a French military commander, governor and Prince Étranger. Having inherited his titles at a young age, Nemours fought for king Henri II during the latter Italian Wars, seeing action at the siege of Metz and the stunning victories of Renty and Calais in 1554 and 1558. Already a commander of French infantry, he received promotion to commander of the light cavalry after the capture of Calais in 1558. A year prior he had accompanied François, Duke of Guise on his entry into Italy, as much for the purpose of campaigning as to escape the king's cousin Antoine of Navarre who was threatening to kill him for his extra-marital pursuit of Navarre's cousin.

Jacques d'Albon, Seigneur de Saint-André was a French governor, Marshal, and favourite of Henri II. He began his career as a confident of the dauphin during the reign of François I. Saint André and the prince were raised together under the governorship of his father at court. In 1547, at the advent of Henri's reign, he was appointed as his father's deputy, serving as lieutenant general for the Lyonnais. Concurrently he entered the king's conseil privé and was made a Marshal and Grand Chamberlain.

The Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was signed on 8 August 1570 by Charles IX of France, Gaspard II de Coligny and Jeanne d'Albret, and ended the 1568 to 1570 Third Civil War, part of the French Wars of Religion.

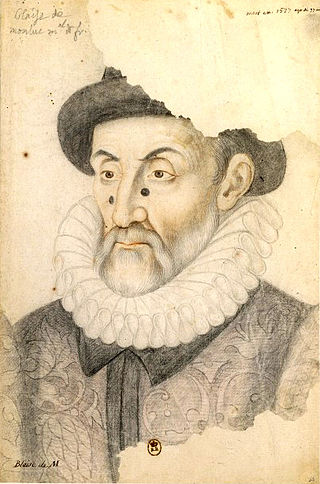

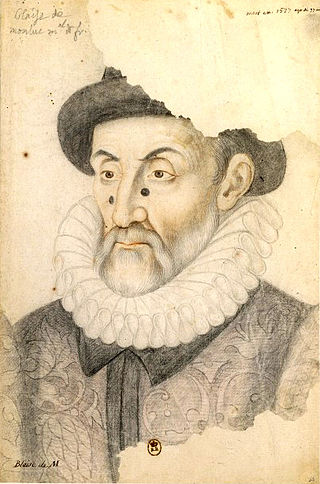

Blaise de Monluc, also known as Blaise de Lasseran-Massencôme, seigneur de Monluc, was a professional soldier whose career began in 1521 and reached the rank of marshal of France in 1574. Written between 1570 and 1576, an account of his life titled Commentaires de Messire Blaise de Monluc was published in 1592, and remains an important historical source for 16th century warfare.

Louis de Bourbon, Duc de Montpensier was the second Duke of Montpensier, a French Prince of the Blood, military commander and governor. He began his military career during the Italian Wars, and in 1557 was captured after the disastrous battle of Saint-Quentin. His liberty restored he found himself courted by the new regime as it sought to steady itself and isolate its opponents in the wake of the Conspiracy of Amboise. At this time Montpensier supported liberalising religious reform, as typified by the Edict of Amboise he was present for the creation of.

Honorat de Savoie, marquis of Villars was a marshal of France and admiral of France. Born into a cadet branch of the house of Savoy, he fought for first Francis I, and then Henri II during the Italian Wars. This included fighting at Hesdin and the battle of Saint-Quentin. During this period he also conducted diplomacy for the French court, and was involved in the negotiations that brought an end to the Italian Wars. Subsequently, he received the office of lieutenant-general of Languedoc, in which he suppressed Huguenots for several years before resigning the commission in 1562.

Charles de Bourbon, Prince de la Roche-sur-Yon,, was a Prince of the Blood and provincial governor under three French kings. He fought in the latter Italian wars during the reign of Henri II, commanding an army during the 1554 campaign into the Spanish Netherlands.

The Battle of Vergt took place on 9 October 1562 during the first French War of Religion, between a Royalist army led by Blaise de Montluc and Huguenot rebels under Symphorien de Duras. The battle was a decisive Royalist victory, which destroyed Duras' army, and prevented him reinforcing Protestant forces in the Loire Valley led by Gaspard II de Coligny and Condé. As such, it is considered a turning point in the first French War of Religion.

The Edict of 19 April was a religious edict promulgated by the regency council of Charles IX of France on 19 April 1561. The edict would confirm the decision of the Estates General of 1560-1 as regarded the amnesty for religious prisoners. The edict would however go further in an effort to calm the unrest that was sweeping France, outlawing the use of religious epithets and providing a pathway for religious exiles to return to the country. Despite not being an edict of toleration for Protestantism, the more conservative Catholics would interpret the edict as a concession to the Huguenots, leading to the Parlement of Paris to remonstrate the crown. The edict would be endorsed and furthered in the more sweeping Edict of July a few months later, before it in turn was superseded by the first edict of toleration, the Edict of Saint-Germain.

Guillaume de Joyeuse (1520–1592) was a French military commander during the French Wars of Religion. Originally destined for the church, he assumed the office of vicomte de Joyeuse upon the death of his elder brother in 1554. He was subsequently appointed at lieutenant-general of Languedoc, under the governor Antoine de Crussol. In this capacity he established himself as a harsh persecutor of Protestantism. When the civil wars broke out in 1562 he assumed his military responsibilities, regularly fighting with the viscomtes de Languedoc throughout the early civil wars. He achieved a notable victory against them in 1568 on the field of Montfran. He did not spread the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew into the territory he controlled and remained loyal to the crown during the fifth civil war, fighting with the Malcontents. In 1582 he was elevated to Marshal of France by Henri III. He found himself increasingly drawn to the Catholic League (France) after its formal formation and when Henri III was assassinated in 1589 he fought against Navarre for Charles, Duke of Mayenne and the league. He died in 1592.

Antoine III de Croÿ, Prince de Porcien (1540-1567) was a French noble and Protestant rebel. Porcien, who held the rank of prince through his sovereign possessions, was a member of the Croÿ family. In 1558 his mother converted to Protestantism, and he followed her in 1560. His house, de Croÿ had been close with the Guise who used them as part of their broader rivalry with the House of Montmorency, supporting their claims that hurt their rival. Porcien broke with the Guise after his conversion. With the advent of Francis II's reign he joined Navarre in opposition to their house. The following year a strategic marriage was arranged for him with Catherine de Clèves which would bring him the County of Eu in 1564.

Antoine de Crussol, 1st Duke of Uzès (1528-1573) was Protestant military commander and peer of France. Raised in a Protestant household, Crussol was an early convert among the elite of France. In 1558 upon his marriage, his barony was elevated to a county by king Henri II. In the troubles that spread through the south in the wake of the Conspiracy of Amboise he was appointed as 'lieutenant and commander' to help bring order back to Provence and Languedoc. In this role he favoured the Protestants, much to the irritation of the Catholic consuls. When the French Wars of Religion broke out, he entered rebellion, accepting the nomination of Governor of Languedoc from the estates of the region. He appointed his relatives to senior positions in his administration.

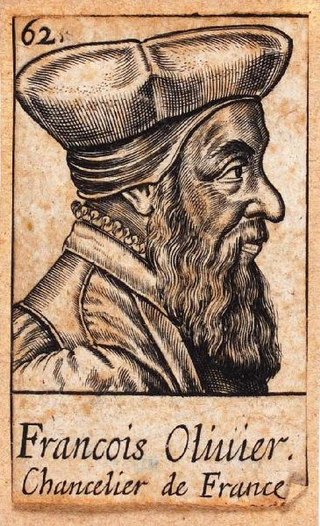

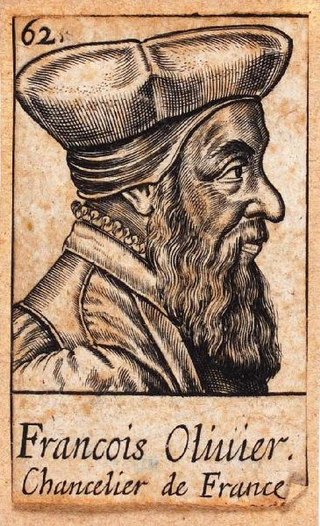

François Olivier, Sieur de Leuvillé was Chancellor of France from 1545 to his death in 1560. After having spent his early career serving in the Parlement and chancelleries of the royal family he was elevated to the prestigious role of Chancellor of France upon the disgrace of Guillaume Poyet.

Guy de Daillon, comte du Lude was a French governor and military commander during the French Wars of Religion. The son of Jean de Daillon, governor of Poitou from 1543 to 1557, Lude inherited his position in the province, becoming governor shortly after his father's death. In 1560 the province, which had been a subsidiary governorship under the governorship of Guyenne was reconfigured to an autonomous entity, and given to Antoine of Navarre to buy his loyalty to the Guise regime. Resultingly Lude was given the role of lieutenant-general of the province instead of governor. However this was functionally a promotion as, when governor of Poitou previously he was subordinate to Navarre's authority in Guyenne. Now when Navarre was absent he had the powers of an autonomous governor.

The 1559–1562 French political crisis was induced by the death of the king Henri II in July 1559. With his death, the throne fell to François II who though not a minor, lacked the ability to command authority due to his young age. Actual power fell to two of Henri II's favourites, the duc de Guise and cardinal de Lorraine who quickly moved to assert a monopoly of their authority over the administration of the kingdom. Royal patronage would flow to them and their clients, with those of their rival, Constable Montmorency quickly starved of royal favour. Having been left with ruinous debts by Henri, they undertook a campaign of aggressive austerity which further alienated many grandees and soldiers who were not shielded from its effects. They also continued the persecution of Protestantism that had transpired under Henri II, though with the young François on the throne the Protestants felt emboldened to resist.

Across France Protestants responded to Condé's manifesto and the beginning of the first French War of Religion by seizing cities and taking control of territories. In total around 20 of the 60 largest cities in the kingdom would fall under rebel Protestant control. Among them Lyon, Tours, Amboise, Poitiers, Caen, Bayeux, Dieppe, Blois, Valence, Rouen, Angers, Le Havre, Grenoble, Auxerre, Beaugency, Montpellier, Mâcon and Le Mans. In the areas of Protestant domination iconoclasm and the seizure of churches was often undertaken. Protestant armies attempted to seize more cities that had not fallen to them. Among the leading Protestant commanders were the comte de Crussol who assumed a position of leadership in Languedoc and Dauphiné; the baron des Adrets in Dauphiné, the seigneur de Duras in Guyenne; the prince de Porcien in Champagne and the comte de Montgommery in Normandie.