The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholics and Protestants from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease directly caused by the conflict, and it severely damaged the power of the French monarchy. One of its most notorious episodes was the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572. The fighting ended with a compromise in 1598, when Henry of Navarre, who had converted to Catholicism in 1593, was proclaimed King Henry IV of France and issued the Edict of Nantes, which granted substantial rights and freedoms to the Huguenots. However, Catholics continued to disapprove of Protestants and of Henry, and his assassination in 1610 triggered a fresh round of Huguenot rebellions in the 1620s.

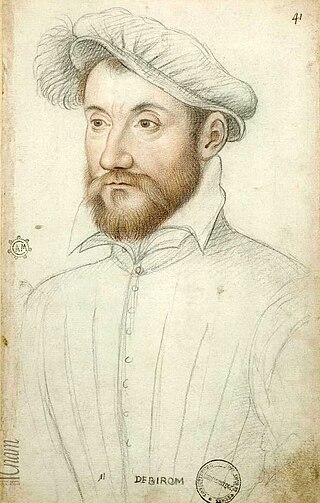

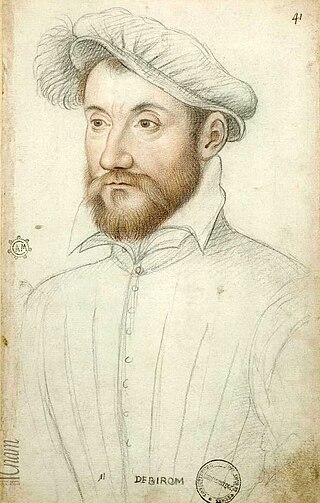

Armand de Gontaut, Baron of Biron was a soldier, diplomat and Marshal of France. Beginning his service during the Italian Wars, Biron served in Italy under Marshal Brissac and Guise in 1557 before rising to command his own cavalry regiment. Returning to France with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis he took up his duties in Guyenne, where he observed the deteriorating religious situation that was soon to devolve into the French Wars of Religion. He fought at the Battle of Dreux in the first civil war. In the peace that followed he attempted to enforce the terms on the rebellious governorship of Provence.

The Edict of Saint-Germain, also known as the Edict of January, was a landmark decree of tolerance promulgated by the regent of France, Catherine de' Medici, in January 1562. The edict provided limited tolerance to the Protestant Huguenots in the Catholic realm, though with counterweighing restrictions on their behaviour. The act represented the culmination of several years of slowly liberalising edicts which had begun with the 1560 Edict of Amboise. After two months the Paris Parlement would be compelled to register it by the rapidly deteriorating situation in the capital. The practical impact of the edict would be highly limited by the subsequent outbreak of the first French Wars of Religion but it would form the foundation for subsequent toleration edicts as the Edict of Nantes of 1598.

Jacques d'Albon, Seigneur de Saint-André was a French governor, Marshal, and favourite of Henri II. He began his career as a confident of the dauphin during the reign of François I. Saint André and the prince were raised together under the governorship of his father at court. In 1547, at the advent of Henri's reign, he was appointed as his father's deputy, serving as lieutenant general for the Lyonnais. Concurrently he entered the king's conseil privé and was made a Marshal and Grand Chamberlain.

The Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was signed on 8 August 1570 by Charles IX of France, Gaspard II de Coligny and Jeanne d'Albret, and ended the 1568 to 1570 Third Civil War, part of the French Wars of Religion.

The Battle of Coutras, fought on 20 October 1587, was a major engagement in the French Religious Wars between a Huguenot (Protestant) army under Henry of Navarre and a royalist army led by Anne, Duke of Joyeuse. Henry of Navarre was victorious, and Joyeuse was killed while attempting to surrender.

Blaise de Monluc, also known as Blaise de Lasseran-Massencôme, seigneur de Monluc, was a professional soldier whose career began in 1521 and reached the rank of marshal of France in 1574. Written between 1570 and 1576, an account of his life titled Commentaires de Messire Blaise de Monluc was published in 1592, and remains an important historical source for 16th century warfare.

The Battle of Moncontour occurred on 3 October 1569 between the royalist Catholic forces of King Charles IX of France, commanded by Henry, Duke of Anjou, and the Huguenots commanded by Gaspard de Coligny.

The Battle of Jarnac on 13 March 1569 was an encounter during the French Wars of Religion between the Catholic forces of Marshal Gaspard de Saulx, sieur de Tavannes, and the Huguenots led by Louis I de Bourbon, prince de Condé. The two forces met outside Jarnac between the right bank of the Charente and the high road between Angoulême and Cognac. The Huguenots were routed and Condé was killed after his surrender and his body paraded on an ass in Jarnac.

The Edict of Amboise, also known as the Edict of Pacification, was signed at the Château of Amboise on 19 March 1563 by Catherine de' Medici, acting as regent for her son Charles IX of France. The Edict ended the first stage of the French Wars of Religion, inaugurating a period of official peace in France by guaranteeing the Huguenots religious privileges and freedoms. However, it was gradually undermined by continuing religious violence at a regional level and hostilities renewed in 1567.

Jean de Monluc, c. 1508 to 12 April 1579, was a French nobleman, clergyman, diplomat and courtier. He was the second son of François de Lasseran de Massencome, a member of the Monluc family; and Françoise d' Estillac. His birthplace is unknown, but it has been observed that his parents spent a great deal of time at their favorite residence at Saint-Gemme in the commune of Saint-Puy near Condom. His elder brother Blaise de Montluc became a soldier and eventually Marshal of France (1574).

Louis de Bourbon, Duc de Montpensier was the second Duke of Montpensier, a French Prince of the Blood, military commander and governor. He began his military career during the Italian Wars, and in 1557 was captured after the disastrous battle of Saint-Quentin. When his liberty was restored, he found himself courted by the new regime as it sought to steady itself and isolate its opponents in the wake of the Conspiracy of Amboise. At this time Montpensier supported liberalising religious reform, as typified by the Edict of Amboise he was present for the creation of.

Vergt is a commune in the Dordogne department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in southwestern France.

Terraube is a commune in the Gers department in southwestern France.

Jeanne d'Albret, also known as Jeanne III, was Queen of Navarre from 1555 to 1572.

Honorat de Savoie, marquis of Villars was a marshal of France and admiral of France. Born into a cadet branch of the house of Savoy, he fought for first Francis I, and then Henri II during the Italian Wars. This included fighting at Hesdin and the battle of Saint-Quentin. During this period he also conducted diplomacy for the French court, and was involved in the negotiations that brought an end to the Italian Wars. Subsequently, he received the office of lieutenant-general of Languedoc, in which he suppressed Huguenots for several years before resigning the commission in 1562.

The Edict of 19 April was a religious edict promulgated by the regency council of Charles IX of France on 19 April 1561. The edict would confirm the decision of the Estates General of 1560-1 as regarded the amnesty for religious prisoners. The edict would however go further in an effort to calm the unrest that was sweeping France, outlawing the use of religious epithets and providing a pathway for religious exiles to return to the country. Despite not being an edict of toleration for Protestantism, the more conservative Catholics would interpret the edict as a concession to the Huguenots, leading to the Parlement of Paris to remonstrate the crown. The edict would be endorsed and furthered in the more sweeping Edict of July a few months later, before it in turn was superseded by the first edict of toleration, the Edict of Saint-Germain.

Charles de Coucis seigneur de Burie (1492-1565) was a Catholic military commander and lieutenant-general of Guyenne. Burie assisted the crown in its efforts to extinguish the embers of the Conspiracy of Amboise in 1560, investigating the situation in Poitiers for the court. This accomplished he returned to his lieutenant-generalship where he spent the next year attempting to suppress the Huguenots of the region. A moderate figure, he looked to find compromise as far as toleration of Protestantism was concerned, conceding the right of Protestants to hold their services in private, and seeking to provide them the right to bury their dead in their own cemetery.

The 1559–1562 French political crisis was induced by the death of the King Henri II in July 1559. With his death, the throne fell to François II who though not a minor, lacked the ability to command authority due to his young age. Actual power fell to two of Henri II's favourites, the duc de Guise and cardinal de Lorraine who quickly moved to assert a monopoly of their authority over the administration of the kingdom. Royal patronage would flow to them and their clients, with those of their rival, Constable Montmorency quickly starved of royal favour. Having been left with ruinous debts by Henri, they undertook a campaign of aggressive austerity which further alienated many grandees and soldiers who were not shielded from its effects. They also continued the persecution of Protestantism that had transpired under Henri II, though with the young François on the throne the Protestants felt emboldened to resist.

Across France Protestants responded to Condé's manifesto and the beginning of the first French War of Religion by seizing cities and taking control of territories. In total around 20 of the 60 largest cities in the kingdom would fall under rebel Protestant control. Among them Lyon, Tours, Amboise, Poitiers, Caen, Bayeux, Dieppe, Blois, Valence, Rouen, Angers, Le Havre, Grenoble, Auxerre, Beaugency, Montpellier, Mâcon and Le Mans. In the areas of Protestant domination iconoclasm and the seizure of churches was often undertaken. Protestant armies attempted to seize more cities that had not fallen to them. Among the leading Protestant commanders were the comte de Crussol who assumed a position of leadership in Languedoc and Dauphiné; the baron des Adrets in Dauphiné, the seigneur de Duras in Guyenne; the prince de Porcien in Champagne and the comte de Montgommery in Normandie.