Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet, was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, Waverley, Old Mortality, The Heart of Mid-Lothian and The Bride of Lammermoor, and the narrative poems The Lady of the Lake and Marmion. He had a major impact on European and American literature.

Ayrshire is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of Renfrewshire and Lanarkshire to the north-east, Dumfriesshire to the south-east, and Kirkcudbrightshire and Wigtownshire to the south. Like many other counties of Scotland it currently has no administrative function, instead being sub-divided into the council areas of North Ayrshire, South Ayrshire and East Ayrshire. It has a population of approximately 366,800.

Westmorland (, formerly also spelt Westmoreland; is a historic county in North West England spanning the southern Lake District and the northern Dales. It had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. Between 1974 and 2023 Westmorland lay within the administrative county of Cumbria. In April 2023, Cumbria County Council will be abolished and replaced with two unitary authorities, one of which, Westmorland and Furness, will cover all of Westmorland, thereby restoring the Westmorland name to a top-tier administrative entity. The people of Westmorland are known as Westmerians.

The Isle of Sheppey is an island off the northern coast of Kent, England, neighbouring the Thames Estuary, centred 42 miles (68 km) from central London. It has an area of 36 square miles (93 km2). The island forms part of the local government district of Swale. Sheppey is derived from Old English Sceapig, meaning "Sheep Island".

Spilsby is a market town, civil parish and electoral ward in the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. The town is adjacent to the main A16, 33 miles (53 km) east of the county town of Lincoln, 17 miles (27 km) north-east of Boston and 13 miles (21 km) north-west of Skegness. It lies at the southern edge of the Lincolnshire Wolds and north of the Fenlands, and is surrounded by scenic walking, nature reserves and other places to visit.

A Pictish stone is a type of monumental stele, generally carved or incised with symbols or designs. A few have ogham inscriptions. Located in Scotland, mostly north of the Clyde-Forth line and on the Eastern side of the country, these stones are the most visible remaining evidence of the Picts and are thought to date from the 6th to 9th century, a period during which the Picts became Christianized. The earlier stones have no parallels from the rest of the British Isles, but the later forms are variations within a wider Insular tradition of monumental stones such as high crosses. About 350 objects classified as Pictish stones have survived, the earlier examples of which holding by far the greatest number of surviving examples of the mysterious symbols, which have long intrigued scholars.

The Archdiocese of Glasgow was one of the thirteen dioceses of the Scottish church. It was the second largest diocese in the Kingdom of Scotland, including Clydesdale, Teviotdale, parts of Tweeddale, Liddesdale, Annandale, Nithsdale, Cunninghame, Kyle, and Strathgryfe, as well as Lennox, Carrick and the part of Galloway known as Desnes.

Carloway is a crofting township and a district on the west coast of the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. The district has a population of around 500. Carloway township is within the parish of Uig, and is situated on the A858.

Breamore is a village and civil parish near Fordingbridge in Hampshire, England. The parish includes a notable Elizabethan country house, Breamore House, built with an E-shaped ground plan. The Church of England parish church of Saint Mary has an Anglo-Saxon rood.

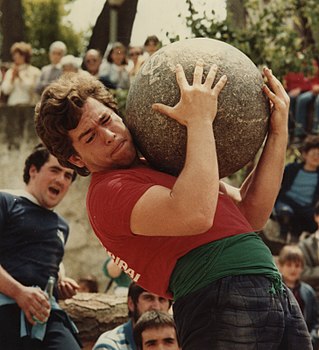

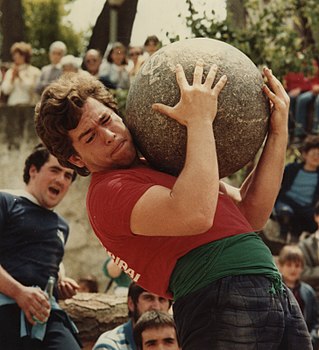

Lifting stones are heavy natural stones which people are challenged to lift, proving their strength. They are common throughout northern Europe, particularly Scotland, Wales, Iceland, Scandinavia and North West England centred around Cumbria.

Rev John Thomson FRSE HonRSA was a Scottish minister of the Church of Scotland and noted amateur landscape painter. He was the minister of Duddingston Kirk from 1805 to 1840.

Clach an Tiompain or The Eagle Stone is a small Class I Pictish stone located on a hill on the northern outskirts of Strathpeffer in Easter Ross, Scotland.

Liberton is a suburb of Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. It is in the south of the city, south of The Inch, east of the Braid Hills, north of Gracemount and west of Moredun.

Kirby Hill, also called Kirby-on-the-Moor, is a village and civil parish about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the market town of Boroughbridge, in the Harrogate district of North Yorkshire, England.

The Hebrides were settled early on in the settlement of the British Isles, perhaps as early as the Mesolithic era, around 8500–8250 BC, after the climatic conditions improved enough to sustain human settlement. There are examples of structures possibly dating from up to 3000 BC, the finest example being the standing stones at Callanish, but some archaeologists date the site as Bronze Age. Little is known of the people who settled in the Hebrides but they were likely of the same Celtic stock that had settled in the rest of Scotland. Settlements at Northton, Harris, have both Beaker & Neolithic dwelling houses, the oldest in the Western Isles, attesting to the settlement.

Craigie Castle, in the old Barony of Craigie, is a ruined fortification situated about 4 miles (6.4 km) southeast of Kilmarnock and 1 mile (1.6 km) southeast of Craigie village, in the Civil Parish of Craigie, South Ayrshire, Scotland. The castle is recognised as one of the earliest buildings in the county. It lies about 1.25 miles (2 km) west-south-west of Craigie church. Craigie Castle is protected as a scheduled monument.

Loans is a village in South Ayrshire near Troon, Scotland. It is located in Dundonald parish on the A759 at the junction with the B746 and a minor road to Dundonald.

Hospitals in medieval Scotland can be dated back to the 12th century. From c. 1144 to about 1650 many hospitals, bedehouses and maisons Dieu were built in Scotland.

Ninestane Rig is a small stone circle in Scotland near the English border. Located in Roxburghshire, near to Hermitage Castle, it was probably made between 2000 BC and 1250 BC, during the Late Neolithic or early Bronze Age. It is a scheduled monument and is part of a group with two other nearby ancient sites, these being Buck Stone standing stone and another standing stone at Greystone Hill. Settlements appear to have developed in the vicinity of these earlier ritual features in late prehistory and probably earlier.

Walter Scott's "Memoirs", first published as "Memoir of the Early Life of Sir Walter Scott, Written by Himself" and also known as the Ashestiel fragment, is a short autobiographical work describing the author's ancestry, parentage, and life up to the age of 22. It is the most important source of information we have on Scott's early life. It was mainly written between 1808 and 1811, then revised and completed in 1826, and first published posthumously in 1837 as Chapter 1 of J. G. Lockhart's multi-volume Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. It was re-edited in 1981 by David Hewitt.