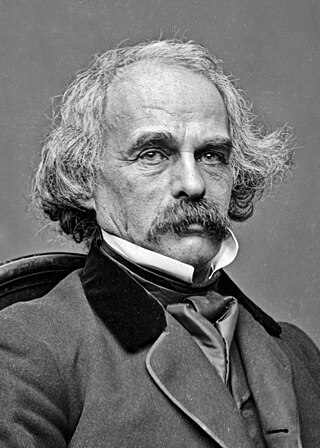

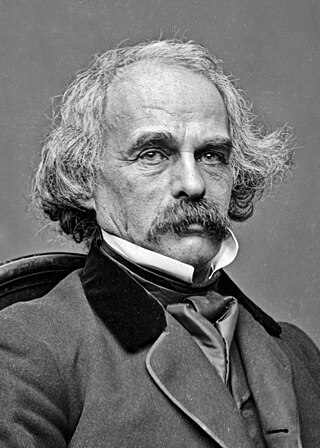

Nathaniel Hawthorne was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, also known as Mother Mary Alphonsa, was an American writer and religious leader. She was a Catholic religious sister, social worker, and foundress of the Dominican Sisters of Hawthorne.

The Marble Faun: Or, The Romance of Monte Beni, also known by the British title Transformation, was the last of the four major romances by Nathaniel Hawthorne, and was published in 1860. The Marble Faun, written on the eve of the American Civil War, is set in a fantastical Italy. The romance mixes elements of a fable, pastoral, gothic novel, and travel guide.

Sophia Amelia Hawthorne was an American painter and illustrator as well as the wife of author Nathaniel Hawthorne. She also published her journals and various articles.

The House of the Seven Gables is a 1668 colonial mansion in Salem, Massachusetts, named for its gables. It was made famous by Nathaniel Hawthorne's 1851 novel The House of the Seven Gables. The house is now a non-profit museum, with an admission fee charged for tours, as well as an active settlement house with programs for the local immigrant community including ESL and citizenship classes. It was built for Captain John Turner and stayed with the family for three generations.

James Thomas Fields was an American publisher, editor, and poet. His business, Ticknor and Fields, was a notable publishing house in 19th century Boston.

Mosses from an Old Manse is a short story collection by Nathaniel Hawthorne, first published in 1846.

William Davis Ticknor I was an American publisher in Boston, Massachusetts, USA, and a founder of the publishing house Ticknor and Fields.

The Old Manse is a historic manse in Concord, Massachusetts, United States, notable for its literary associations. It is open to the public as a nonprofit museum owned and operated by the Trustees of Reservations. The house is located on Monument Street, with the Concord River just behind it. The property neighbors the North Bridge, a part of Minute Man National Historical Park.

The Wayside is a historic house in Concord, Massachusetts. The earliest part of the home may date to 1717. Later it successively became the home of the young Louisa May Alcott and her family, who named it Hillside, author Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family, and children's writer Margaret Sidney. It became the first site with literary associations acquired by the National Park Service and is now open to the public as part of Minute Man National Historical Park.

Twice-Told Tales is a short story collection in two volumes by Nathaniel Hawthorne. The first volume was published in the spring of 1837 and the second in 1842. The stories had all been previously published in magazines and annuals, hence the name.

Julian Hawthorne was an American writer and journalist, the son of novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody. He wrote numerous poems, novels, short stories, mysteries and detective fiction, essays, travel books, biographies, and histories.

The House of the Seven Gables: A Romance is a Gothic novel written beginning in mid-1850 by American author Nathaniel Hawthorne and published in April 1851 by Ticknor and Fields of Boston. The novel follows a New England family and their ancestral home. In the book, Hawthorne explores themes of guilt, retribution, and atonement, and colors the tale with suggestions of the supernatural and witchcraft. The setting for the book was inspired by the Turner-Ingersoll Mansion, a gabled house in Salem, Massachusetts, belonging to Hawthorne's cousin Susanna Ingersoll, as well as ancestors of Hawthorne who had played a part in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. The book was well received upon publication and later had a strong influence on the work of H. P. Lovecraft. The House of the Seven Gables has been adapted several times to film and television.

A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys (1851) is a children's book by American author Nathaniel Hawthorne in which he retells several Greek myths. It was followed by a sequel, Tanglewood Tales.

"The Ambitious Guest" is a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne. First published in The New-England Magazine in June 1835, it was republished in the second volume of Twice-Told Tales in 1841.

"Roger Malvin's Burial" is a short story by American author Nathaniel Hawthorne. It was first published anonymously in 1832 before its inclusion in the 1846 collection Mosses from an Old Manse. The tale concerns two fictional colonial survivors returning home after the historical battle known as Battle of Pequawket.

Ticknor and Fields was an American publishing company based in Boston, Massachusetts. Founded as a bookstore in 1832, the business would publish many 19th century American authors including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry James, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry David Thoreau, and Mark Twain. It also became an early publisher of The Atlantic Monthly and North American Review.

The United States Consulate in Liverpool, England, was established in 1790, and was the first overseas consulate founded by the then fledgling United States of America. Liverpool was at the time an important center for transatlantic commerce and a vital trading partner for the former Thirteen Colonies. Among those who served the United States as consul in Liverpool were the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, the spy Thomas Haines Dudley, and John S. Service, who was driven out of the United States Foreign Service by McCarthyite persecution. After World War II, as Liverpool declined in importance as an international port, the consulate was eventually closed down.

The Token (1829–1842) was an annual, illustrated gift book, containing stories, poems and other light and entertaining reading. In 1833, it became The Token and Atlantic Souvenir.

"The Celestial Railroad" is short story by American author Nathaniel Hawthorne. In the allegorical tale, Hawthorne adopts the style and content of the seventeenth-century allegory The Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan. Where Bunyan's tale portrays a Christian's spiritual "journey" through life, Hawthorne's satirizes many contemporary religious practices and philosophies, including transcendentalism.