A gravestone or tombstone is a marker, usually stone, that is placed over a grave. A marker set at the head of the grave may be called a headstone. An especially old or elaborate stone slab may be called a funeral stele, stela, or slab. The use of such markers is traditional for Chinese, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic burials, as well as other traditions. In East Asia, the tomb's spirit tablet is the focus for ancestral veneration and may be removable for greater protection between rituals. Ancient grave markers typically incorporated funerary art, especially details in stone relief. With greater literacy, more markers began to include inscriptions of the deceased's name, date of birth, and date of death, often along with a personal message or prayer. The presence of a frame for photographs of the deceased is also increasingly common.

Transcona is a ward and suburb of Winnipeg, Manitoba, located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) east of the downtown area.

Bayside Cemetery is a Jewish cemetery at 80-35 Pitkin Avenue in Ozone Park, Queens, New York City. It covers about 12 acres (4.9 ha) and has about 35,000 interments. It is bordered on the east by Acacia Cemetery, on the north by Liberty Avenue, on the west by Mokom Sholom Cemetery, and on the south by Pitkin Avenue.

West Kildonan is a residential suburb within the Old Kildonan and Mynarski city wards of Winnipeg, Manitoba, lying on the west side of the Red River of the North, and immediately north of the old City of Winnipeg in the north-central part of the city.

The Old Jewish Cemetery is a Jewish cemetery in Prague, Czech Republic, which is one of the largest of its kind in Europe and one of the most important Jewish historical monuments in Prague. It served its purpose from the first half of the 15th century until 1786. Renowned personalities of the local Jewish community were buried here; among them rabbi Jehuda Liva ben Becalel – Maharal, businessman Mordecai Meisel (1528–1601), historian David Gans and rabbi David Oppenheim (1664–1736). Today the cemetery is administered by the Jewish Museum in Prague.

Belfast City Cemetery is a large cemetery in west Belfast, Northern Ireland. It lies within the townland of Ballymurphy, between Falls Road and Springfield Road, near Milltown Cemetery. It is maintained by Belfast City Council. Vandalism in the cemetery is widespread.

The Ohel is an ohel in Cambria Heights, Queens, New York City, where Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson and his father-in-law Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, the two most recent rebbes of the Chabad-Lubavitch dynasty, are buried. Both Jews and non-Jews visit The Ohel for prayer, and approximately 50,000 people make an annual pilgrimage there on the anniversary of Schneerson's death.

Yisroel Meir Gabbai is a Breslover Hasid who travels the world to locate, repair and maintain Jewish cemeteries, kevarim (gravesites) and ohels of Torah notables and tzaddiks. He is the founder of Agudas Ohalei Tzadikim.

The Jewish Cemetery in Worms or Heiliger Sand, in Worms, Germany, is usually called the oldest surviving Jewish cemetery in Europe, although the Jewish burials in the Jewish sections of the Roman catacombs predate it by a millennium. The Jewish community of Worms was established by the early eleventh century, and the oldest tombstone still legible dates from 1058/59. The cemetery was closed in 1911, when a new cemetery was inaugurated. Some family burials continued until the late 1930s. The older part still contains about 1,300 tombstones, while the newer part contains more than 1,200. The cemetery is protected and cared for by the city of Worms, the Jewish community of Mainz-Worms, and the Landesdenkmalamt of Rhineland-Palatinate. The Salomon L. Steinheim-Institute for German-Jewish History at the University of Duisburg-Essen has been documenting and researching the site since 2005. Because of its cultural importance and preservation, the Jewish Cemetery was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2021.

Shaarey Zedek Synagogue is the oldest synagogue in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Formed in 1880, the congregation's first building was constructed by Philip Brown and several others in 1890. Architect Charles Henry Wheeler designed the original Synagogue on King Street (1889–90).

Solomon Frank was an American–Canadian Orthodox rabbi, speaker, and civic and community leader. He served as rabbinic leader of Shaarey Zedek Synagogue of Winnipeg, Canada, from 1926 to 1947, and spiritual leader of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue of Montreal from 1947 until his death. Active in interfaith affairs, he was also a chaplain for Jewish and Christian organizations and hospitals. In Montreal, he broadcast a weekly radio message on Jewish thought and practice for more than 25 years.

Sanhedria Cemetery is a 27-dunam (6.67-acre) Jewish burial ground in the Sanhedria neighborhood of Jerusalem, adjacent to the intersection of Levi Eshkol Boulevard, Shmuel HaNavi Street, and Bar-Ilan Street. Unlike the Mount of Olives and Har HaMenuchot cemeteries that are located on the outer edges of the city, Sanhedria Cemetery is situated in the heart of western Jerusalem, in proximity to residential housing. It is operated under the jurisdiction of the Kehilat Yerushalayim chevra kadisha and accepts Jews from all religious communities. As of the 2000s, the cemetery is nearly filled to capacity.

Hampton Cemetery is a historic cemetery in downtown Hampton, Arkansas. The 0.5-acre (0.20 ha) cemetery is located near the center of town, not far from the Calhoun County Courthouse, and immediately adjacent to the Hampton Church of Christ. The cemetery is said to have been used as a burying ground since the first days of settlement in the area, although the first marked grave is dated 1878. The town decided in 1920 to stop allowing burials other than those already reserved, and the last burial took place in the cemetery in 1969. There are estimated to be 139 burials in the cemetery, although only 103 are marked. Most of the marked graves are dated between 1890 and 1920.

The Chesed Shel Emeth Cemetery is a Jewish graveyard located in University City, Missouri, an inner ring suburb of St. Louis.

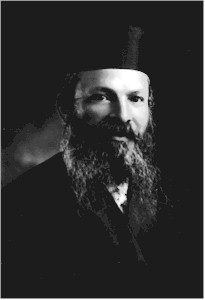

Israel Isaac Kahanovitch was a Polish Canadian Orthodox Jewish rabbi who served as Chief Rabbi of Winnipeg and Western Canada for nearly 40 years. Widely respected for his Talmudic erudition and oratory skills, he strengthened Jewish educational, religious, and social institutions and worked to bridge the divide between religious and secular Jews in Canada. He was a founding member of the Canadian Jewish Congress. In 2010, he was named a Person of National Historic Significance by the Government of Canada.

Abba Avraham Shmuel Twersky (1872–1947), known as Shmuel Abba Twersky, was a Rebbe of the Makarover Hasidic dynasty. He succeeded his father as Makarover Rebbe of Berdichev, Ukraine, in 1920, and presided as Makarover Rebbe of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, from 1927 to 1947.

Maitland Jewish Cemetery is a heritage-listed closed cemetery at 112-114 Louth Park Road, South Maitland, City of Maitland, New South Wales, Australia. It was in use from 1846 to 1934. The property is owned by Maitland City Council. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 7 March 2014.

Shaarey Zedek Cemetery is a Conservative Jewish burial ground in the North End of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Operated by the Shaarey Zedek Synagogue, it is the largest Jewish cemetery in the Canadian Prairies, with more than 8,000 graves as of 1996. In 2012, a Jewish interfaith burial ground was installed in a fenced-off section with a separate entrance to accommodate interment of Jews alongside their non-Jewish spouses. The cemetery features a war memorial honouring Winnipeg residents who fell in World War I and World War II.

Hebrew Sick Benefit Cemetery is a Jewish cemetery in Winnipeg, Canada. Founded in 1911, it contained approximately 3,500 graves as of 1996. It also contains a war memorial to fallen Jewish servicemen in World War II.