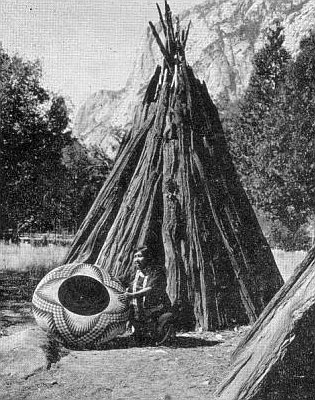

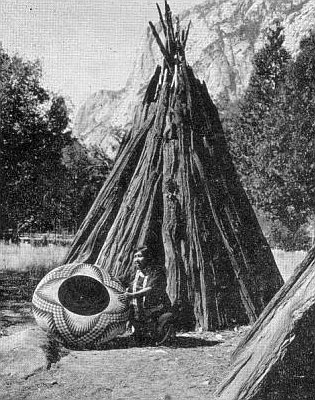

The Pomo are a Native American people of California. Historical Pomo territory in Northern California was large, bordered by the Pacific Coast to the west, extending inland to Clear Lake, mainly between Cleone and Duncans Point. One small group, the Tceefoka, lived in the vicinity of present-day Stonyford, Colusa County, where they were separated from the majority of Pomo lands by Yuki and Wintuan speakers.

Bayou Teche is a 125-mile-long (201 km) waterway in south central Louisiana in the United States. Bayou Teche was the Mississippi River's main course when it developed a delta about 2,800 to 4,500 years ago. Through a natural process known as deltaic switching, the river's deposits of silt and sediment cause the Mississippi to change its course every thousand years or so.

Arundinaria is a genus of bamboo in the grass family the members of which are referred to generally as cane. Arundinaria is the only bamboo native to North America, with a native range from Maryland south to Florida and west to the southern Ohio Valley and Texas. Within this region Arundinaria canes are found from the Coastal Plain to medium elevations in the Appalachian Mountains.

The Chitimacha are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands in Louisiana. They are a federally recognized tribe, the Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana.

Nanyehi, known in English as Nancy Ward, was a Beloved Woman and political leader of the Cherokee. She advocated for peaceful coexistence with European Americans and, late in life, spoke out for Cherokee retention of tribal hunting lands. She is credited with the introduction of dairy products to the Cherokee economy.

The Atakapa or Atacapa were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, who spoke the Atakapa language and historically lived along the Gulf of Mexico in what is now Texas and Louisiana.

The Southern Paiute people are a tribe of Native Americans who have lived in the Colorado River basin of southern Nevada, northern Arizona, and southern Utah. Bands of Southern Paiute live in scattered locations throughout this territory and have been granted federal recognition on several reservations. Southern Paiute's traditionally spoke Colorado River Numic, which is now a critically endangered language of the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family, and is mutually intelligible with Ute. The term Paiute comes from paa and refers to their preference for living near water sources. Before European colonization, they practiced springtime, floodplain farming with reservoirs and irrigation ditches for corn, squash, melons, gourds, sunflowers, beans, and wheat.

Chitimacha is a language isolate historically spoken by the Chitimacha people of Louisiana, United States. It became extinct in 1940 with the death of the last fluent speaker, Delphine Ducloux.

Basket weaving is the process of weaving or sewing pliable materials into three-dimensional artifacts, such as baskets, mats, mesh bags or even furniture. Craftspeople and artists specialized in making baskets may be known as basket makers and basket weavers. Basket weaving is also a rural craft.

The Taensa were a Native American people whose settlements at the time of European contact in the late 17th century were located in present-day Tensas Parish, Louisiana. The meaning of the name, which has the further spelling variants of Taenso, Tinsas, Tenza or Tinza, Tahensa or Takensa, and Tenisaw, is unknown. It is believed to be an autonym. The Taensa should not be confused with the Avoyel, known by the French as the petits Taensas, who were mentioned in writings by explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville in 1699. The Taensa are more closely related to the Natchez people and both are considered descendants of the late prehistoric Plaquemine culture.

Kimberly M. Blaeser is a Native American poet and writer enrolled in the White Earth Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. She was the Wisconsin Poet Laureate 2015–16.

The Opelousa were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands in Louisiana. They lived near present-day Opelousas, Louisiana, west of the lower Mississippi River, in the 18th century. At various times, they allied with the neighboring Atakapa and Chitimacha peoples.

Essie Pinola Parrish (1902–1979), was a Kashaya Pomo spiritual leader and exponent of native traditions. She was also a notable basket weaver.

Louisiana Highway 87 (LA 87) is a state highway located in southern Louisiana. It runs 42.04 miles (67.66 km) in a northwest to southeast direction from LA 86 in New Iberia to the junction of two local roads north of Centerville.

Karenne Wood was a member of the Monacan Indian tribe who was known for her poetry and for her work in tribal history. She served as the director of the Virginia Indian Programs at Virginia Humanities, in Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S. She directed a tribal history project for the Monacan Nation, conducted research at the National Museum of the American Indian, and served on the National Congress of American Indians' Repatriation Commission. In 2015, she was named one of the Library of Virginia's "Virginia Women in History".

The Atchafalaya Basin Mounds is an archaeological site originally occupied by peoples of the Coastal Coles Creek and Plaquemine cultures beginning around 980 CE, and by their presumed historic period descendants, the Chitimacha, during the 18th century. It is located in St. Mary Parish, Louisiana on the northern bank of Bayou Teche at its confluence with the Lower Atchafalaya River. It consists of several earthen platform mounds and a shell midden situated around a central plaza. The site was visited by Clarence Bloomfield Moore in 1913.

Ada Thomas was a rivercane basket weaver from Louisiana. She excelled in double-weave, split rivercane basketry.

Molly Neptune Parker was an American basket weaver. She became well known for her artistry, with her works selling for thousands of dollars. As a co-founder and president of the Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance, she tutored young people in the traditional craft and also educated four generations of her own family. She was also the first woman lieutenant governor of Indian Township, one of the two governing bodies of the Passamaquoddy tribe.

Luwana Quitiquit was a Native American administrator, activist, and basket weaver. During the Occupation of Alcatraz she worked as one of the cooks who provided food to those living on the island. Her career was as an administrator for various California Indian organizations. Subsequently, she became a well-known doll maker, basketweaver, jeweler, and teacher of Pomo handicrafts. In 2008, she and her family were disenrolled from the Robinson Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California. She fought the action claiming it was politically motivated until her death. Posthumously, in 2017, her membership, as well as for her other family members, was reinstated in the first known case where a tribe reversed its decision on membership termination without a court ruling.

Sarah Sense is an American Chitimacha/Choctaw visual artist known for large scale weavings of photographs, maps, and cultural ephemera to create social and political statements. Sense employs traditional weaving techniques from her Chitimacha and Choctaw family to create two-dimensional photo weavings and three-dimensional photo baskets.