The Black and White Minstrel Show was a British light entertainment show on BBC prime-time television that ran from 1958 to 1978. The weekly variety show presented traditional American minstrel and country songs, as well as show tunes and music hall numbers, lavishly costumed and often presented with cast members in blackface. A popular stage show, based on the TV show with the same title, ran from 1962 to 1972 at the Victoria Palace Theatre, London. This was followed by tours of UK seaside resorts until 1989, and tours in Australia and New Zealand. From early in its history, and increasingly throughout its run, the show received criticism for its racist premise and content.

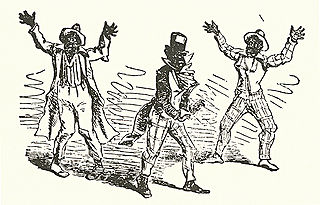

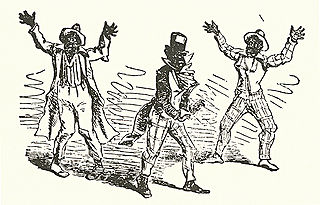

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of theater developed in the early 19th century. The shows were performed by mostly white actors wearing blackface makeup for the purpose of comically portraying racial stereotypes of African Americans. There were also some African-American performers and black-only minstrel groups that formed and toured. Minstrel shows stereotyped blacks as dimwitted, lazy, buffoonish, cowardly, superstitious, and happy-go-lucky. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people specifically of African descent.

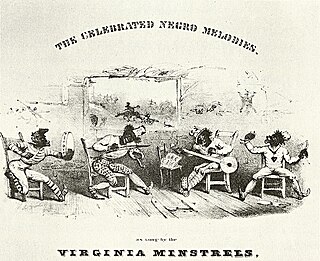

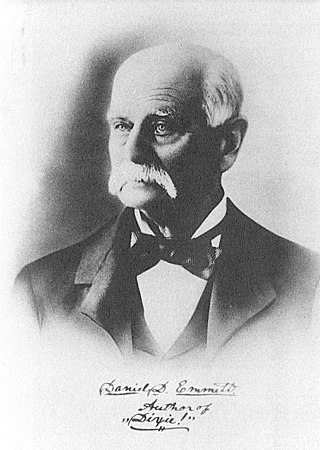

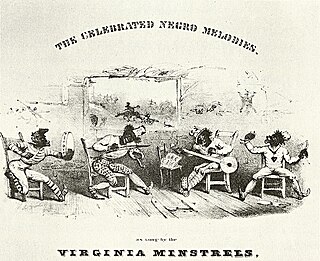

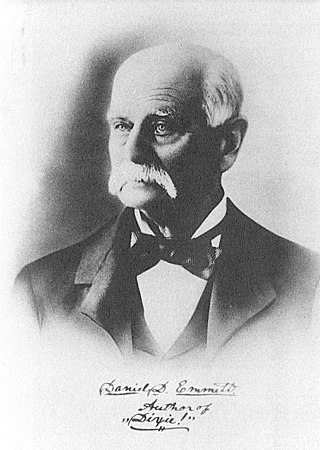

The Virginia Minstrels or Virginia Serenaders was a group of 19th-century American entertainers who helped invent the entertainment form known as the minstrel show. Led by Dan Emmett, the original lineup consisted of Emmett, Billy Whitlock, Dick Pelham, and Frank Brower.

Daniel Decatur Emmett was an American composer, entertainer, and founder of the first troupe of the blackface minstrel tradition, the Virginia Minstrels. He is most remembered as the composer of the song "Dixie".

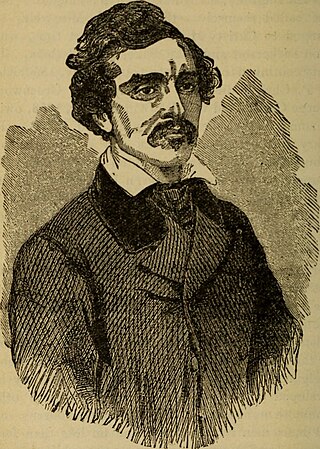

George N. Christy was one of the leading blackface performers during the early years of the blackface minstrel show in the 1840s.

Edwin Pearce Christy was an American composer, singer, actor and stage producer. He is more commonly known as E. P. Christy, and was the founder of the blackface minstrel group Christy's Minstrels. He toured England performing.

Old Corn Meal, or Signor Cormeali, was an African-American street vendor in New Orleans, Louisiana who became famous in the late 1830s for singing and dancing while he sold his wares. He is one of the earliest known African Americans to have had a documented influence on the development of blackface minstrelsy specifically and American popular music in general.

The Ethiopian Serenaders was an American blackface minstrel troupe successful in the 1840s and 1850s. Through various line-ups they were managed and directed by James A. Dumbolton (c.1808–?), and are sometimes mentioned as the Boston Minstrels, Dumbolton Company or Dumbolton's Serenaders.

Joel Walker Sweeney, also known as Joe Sweeney, was an American musician and early blackface minstrel performer. He is known for popularizing the playing of the banjo and has often been credited with advancing the physical development of the modern five-string banjo.

Bryant's Minstrels was a blackface minstrel troupe that performed in the mid-19th century, primarily in New York City. The troupe was led by the O'Neill brothers from upstate New York, who took the stage name Bryant.

A walkaround was a dance from the blackface minstrel shows of the 19th century. The walkaround began in the 1840s as a dance for one performer, but by the 1850s, many dancers or the entire troupe participated. The walkaround often served as the finale to the first half of the minstrel show, the opening semicircle. Minstrels also wrote songs called "walkarounds", which were specifically intended for this dance; "Dixie" is probably the most famous example.

Mechanics' Hall was a meeting hall and theatre seating 2,500 people located at 472 Broadway in New York City, United States. It had a brown façade. Built by the Mechanics' Society for their monthly meetings in 1847, it was also used for banquets, luncheons, and speeches held by other groups.

Richard Ward "Dick" Pelham, born Richard Ward Pell, was an American blackface performer. He was born in New York City.

William M. Whitlock was an American blackface performer. He began his career in entertainment doing blackface banjo routines in circuses and dime shows, and by 1843 he was well known in New York City. He is best known for his role in forming the original minstrel show troupe, the Virginia Minstrels.

The stump speech was a comic monologue from blackface minstrelsy. A typical stump speech consisted of malapropisms, nonsense sentences, and puns delivered in a parodied version of Black Vernacular English. The stump speaker wore blackface makeup and moved about like a clown. Topics varied from pure nonsense to parodies of politics, science, and social issues, as well as satirical commentary on political and social issues. The stump speech was a precursor to modern stand-up comedy.

Francis Marion Brower was an American blackface performer active in the mid-19th century. Brower began performing blackface song-and-dance acts in circuses and variety shows when he was 13. He eventually introduced the bones to his act, helping to popularize it as a blackface instrument. Brower teamed with various other performers, forming his longest association with banjoist Dan Emmett beginning in 1841. Brower earned a reputation as a gifted dancer. In 1842, Brower and Emmett moved to New York City. They were out of work by January 1843, when they teamed up with Billy Whitlock and Richard Pelham to form the Virginia Minstrels. The group was the first to perform a full minstrel show as a complete evening's entertainment. Brower pioneered the role of the endman.

Swanee River is a 1939 American biographical musical drama film directed by Sidney Lanfield and starring Don Ameche, Andrea Leeds, Al Jolson, and Felix Bressart. It is a biopic about Stephen Foster, a songwriter from Pittsburgh who falls in love with the South, marries a Southern girl, then is accused of sympathizing when the Civil War breaks out. Typical of 20th Century-Fox biographical films of the time, the film was more fictional than it was factual.

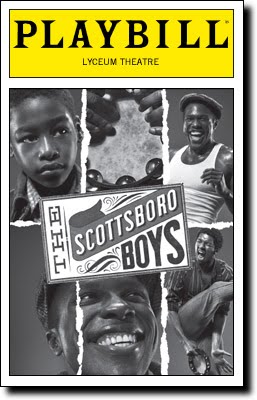

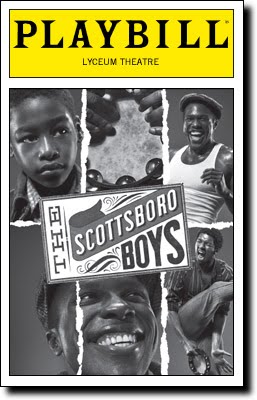

The Scottsboro Boys is a musical with a book by David Thompson, music by John Kander and lyrics by Fred Ebb. Based on the Scottsboro Boys trial, the musical is one of the last collaborations between Kander and Ebb prior to the latter's death. The musical has the framework of a minstrel show, altered to "create a musical social critique" with a company that, except for one, consists "entirely of African-American performers".

Julia Wildman Gould was an English-born singer and actress, who was the first woman to become a leading blackface performer in American minstrel shows.