Related Research Articles

Julia Constanza Burgos García, also known as Julia de Burgos, was a Puerto Rican poet, journalist, independista, Nuyorican, and teacher. As an advocate of Puerto Rican independence, she served as Secretary General of the Daughters of Freedom, the women's branch of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. She was also a civil rights activist for women and African and Afro-Caribbean writers.

José de Diego y Martínez was a Puerto Rican statesman, journalist, poet, lawyer, and advocate for Puerto Rico's political autonomy in union with Spain and later of Puerto Rican independence from the United States who was referred to by his peers as "The Father of the Puerto Rican Independence Movement".

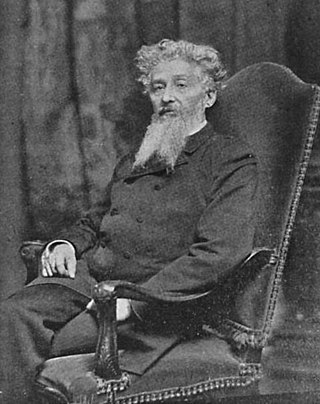

Eugenio María de Hostos y de Bonilla, known as El Gran Ciudadano de las Américas, was a Puerto Rican educator, philosopher, intellectual, lawyer, sociologist, novelist, and Puerto Rican independence advocate.

Ramón Emeterio Betances y Alacán was a Puerto Rican independence advocate and medical doctor. He was the primary instigator of the Grito de Lares revolt and designer of the Grito de Lares flag. Since the Grito galvanized a burgeoning nationalist movement among Puerto Ricans, Betances is also considered to be the father of the Puerto Rican independence movement and the ElPadre de la Patria . His charitable deeds for people in need, earned him the moniker of El Padre de los Pobres .

Grito de Lares, also referred to as the Lares revolt, the Lares rebellion, the Lares uprising, or the Lares revolution, was the first of two short-lived revolts against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico, staged by the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico on September 23, 1868. Having been planned, organized, and launched in the mountainous western municipality of Lares, the revolt is known as the Grito de Lares . Three decades after rebelling in Lares, the revolutionary committee carried out a second unsuccessful revolt in the neighboring southwestern municipality of Yauco, known as the Intentona de Yauco. The Grito de Lares flag is recognized as the first flag of Puerto Rico.

Lola Rodríguez de Tió was the first Puerto Rican-born woman poet to establish herself a reputation as a great poet throughout all of Latin America. A believer in women's rights, she was also committed to the abolition of slavery and the independence of Puerto Rico.

Mariana Bracetti Cuevas was a patriot and leader of the Puerto Rico independence movement. In 1868, she knitted the Grito de Lares flag that was intended to be used as the national emblem of Puerto Rico in its first of two attempts to overthrow Spanish rule, and to establish the island as a sovereign republic. As the flag of the Grito de Lares revolt, Bracetti's creation became known as the Bandera del Grito de Lares , most commonly known as the Bandera de Lares . Today, the flag is the official flag of the municipality of Lares, Puerto Rico.

Mathias Brugman, a.k.a. Mathias Bruckman, was a leader in Puerto Rico's independence revolution against Spain known as El Grito de Lares .

Manuel Rojas Luzardo was a Puerto Rican-Venezuelan commander of the Puerto Rican Liberation Army and one of the main leaders of the Grito de Lares uprising against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico.

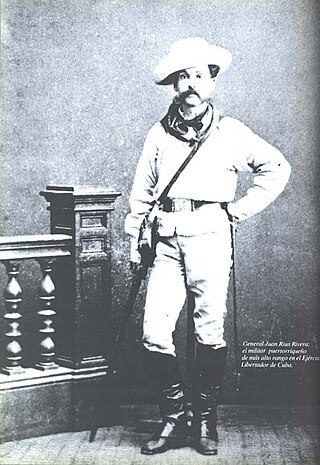

General Juan Rius Rivera, was the soldier and revolutionary leader from Puerto Rico to have reached the highest military rank in the Cuban Liberation Army and to hold Cuban ministerial offices after independence. In his later year, he also became a successful businessperson in Honduras.

Muna Lee was an American poet, author, and activist, who first became known and widely published as a lyric poet in the early 20th century. She also was known for her writings that promoted Pan-Americanism and feminism. She translated and published in Poetry a 1925 landmark anthology of Latin American poets, and continued to translate from poetry in Spanish.

Nicholasa Mohr is one of the best known Nuyorican writers, born in the United States to Puerto Rican parents. In 1973, she became the first Nuyorican woman in the 20th century to have her literary works published by the major commercial publishing houses, and has had the longest creative writing career of any Nuyorican female writer for these publishing houses. She centers her works on the female experience as a child and adult in Puerto Rican communities in New York City, with much of writing containing semi-autobiographical content. In addition to her prominent novels and short stories, she has written screenplays, plays, and television scripts.

Luz María "Luzma" Umpierre-Herrera is a Puerto Rican advocate for human rights, a New-Humanist educator, poet, and scholar. Her work addresses a range of critical social issues including activism and social equality, the immigrant experience, bilingualism in the United States, and LGBT matters. Luzma authored six poetry collections and two books on literary criticism, in addition to having essays featured in academic journals.

The Intentona de Yauco of March 24–26, 1897 was the second and final short-lived revolt against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico. It was staged by the pro-independence Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico in the southwestern municipality of Yauco, 29 years after the first unsuccessful revolt, known as the Grito de Lares. During the Intentona de Yauco, the current flag of Puerto Rico was flown on the island for the first time.

Francisco Rojas Tollinchi, was a Puerto Rican poet, civic leader and journalist.

María de las Mercedes Barbudo was a Puerto Rican political activist, the first woman Independentista in the island, and a "Freedom Fighter". At the time, the Puerto Rican independence movement had ties with the Venezuelan rebels led by Simón Bolívar.

José Gualberto Padilla, also known as El Caribe, was a physician, poet, journalist, politician, and advocate for Puerto Rico's independence. He suffered imprisonment and constant persecution by the Spanish Crown in Puerto Rico because his patriotic verses, social criticism and political ideals were considered a threat to Spanish Colonial rule of the island.

Antonio Vélez Alvarado was a Puerto Rican journalist, politician and revolutionary who was an advocate of Puerto Rican independence. He is also known as "the Father of the Puerto Rican Flag". A close friend of Cuban patriot José Martí, Vélez Alvarado joined the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee in New York City and is among those who allegedly designed the Flag of Puerto Rico. Vélez Alvarado was one of the founding fathers of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party.

The recorded history of Puerto Rican women can trace its roots back to the era of the Taíno, the indigenous people of the Caribbean, who inhabited the island that they called Borinquen before the arrival of Spaniards. During the Spanish colonization the cultures and customs of the Taíno, Spanish, African and women from non-Hispanic European countries blended into what became the culture and customs of Puerto Rico.

Ana Irma Rivera Lassén is an Afro-Puerto Rican attorney who is a current Member of the Puerto Rican Senate, elected on November 3, 2020, and who previously served as the head of the Bar Association of Puerto Rico from 2012 to 2014. She was the first black woman, and third female, to head the organization. She is a feminist and human rights activist, who is also openly lesbian. She has received many awards and honors for her work in the area of women's rights and human rights, including the Capetillo-Roqué Medal from the Puerto Rican Senate, the Martin Luther King/Arturo Alfonso Schomburg Prize, and the Nilita Vientós Gastón Medal. She is a practicing attorney and serves on the faculty of several universities in Puerto Rico; she currently serves on the Advisory Committee on Access to Justice of the Puerto Rican Judicial Branch.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Vera-Rojas, Maria Teresa (2008). "Betances Jaeger, Clotilde". Greenwood Encyclopedia of Latino Literature. 1: 126.

- ↑ Ruiz, Vicki L.; Korrol, Virginia Sánchez (2006-05-03). Latinas in the United States, set: A Historical Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0253111692.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Vera-Rojas 2008, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 4 Marino, Katherine (August 2, 2012). "The heritage of Latin American women's political empowerment". Gender News, The Clayman Institute for Gender Research. Archived from the original on May 23, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Patterson, Martha H. (2008). "La Mujer Nueva [The New Woman]". The American New Woman Revisited: A Reader, 1894-1930: 124.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Acosta-Belen, Edna (2006). "Betances Jaeger, Clotilde". Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia: 88.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Acosta-Belen 2006, p. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Vera-Rojas 2008, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Vera-Rojas 2008, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 4 Patterson 2008, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Patterson 2008, p. 125.