Paulus Hook is a community on the Hudson River waterfront in Jersey City, New Jersey. It is located one mile across the river from Manhattan. The name Hook comes from the Dutch word "hoeck", which translates to "point of land." This "point of land" has been described as an elevated area, the location of which today is bounded by Montgomery, Hudson, Dudley, and Van Vorst Streets.

Richard Phelan, D.D. was an Irish-born prelate of the Roman Catholic Church who served as the fourth bishop of the Diocese of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, in the United States from 1889 to 1904.

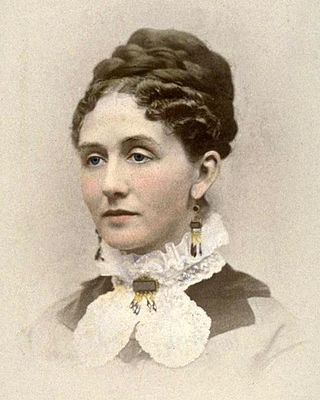

Sarah Brown Ingersoll Cooper was an American educator, author, evangelist, philanthropist, and civic activist. She is remember as a religious teacher and her efforts to increase the wide interest in kindergarten work. Cooper served as first president of the International Kindergarten Union, president of the National Kindergarten Union, president and vice-president of the Woman's Press Association, president of the Woman's Suffrage Association, and president of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union.

Woman's Foreign Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church was one of three Methodist organizations in the United States focused on women's foreign missionary services; the two others were the WFMS of the Free Methodist Church of North America and the WFMS of the Methodist Protestant Church.

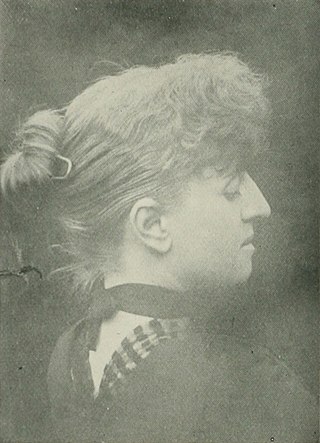

Dorothea Rhodes Lummis Moore was an American physician, writer, newspaper editor, and activist. Although a successful student of music in the New England Conservatory of Music, in Boston, she entered the medical school of Boston University in 1881, and graduated with honors in 1884. In 1880, she married Charles Fletcher Lummis, and in 1885, moved to Los Angeles, California, where she began practicing medicine. She worked as dramatic editor, musical editor, and critic at the Los Angeles Times. She was instrumental in the formation of a humane society which was brought about through her observations of the neglect and cruelty to the children of the poor, and Mexican families, visited in her practice; and the establishment of the California system of juvenile courts.

Lillian Resler Harford was an American church organizer, editor, and author. She was an active worker in the Woman's Missionary Association of her church, the United Brethren in Christ, and delivered lectures for the Women's Missionary Society. In 1880, she was one of the two delegates sent by the Association to the World's Missionary Conference in London She became the longest-serving president of the Association. Harford died in 1935.

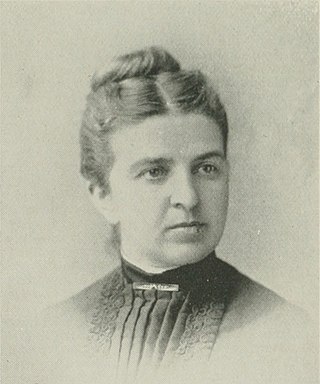

Lucretia Blankenburg was an American second-generation suffragist, social activist, civic reformer, and writer. During the period of 1892 until 1908, she served as president of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association.

The College Settlements Association (CSA) was an American organization founded during the settlement movement era which provided support and control of college settlements for women. Organized February 1890, it was incorporated on January 5, 1894. The settlement houses were established by college women, were controlled by college women, and had a majority of college women as residents. The CSA was devised to unite college women in the trend of a modern movement, to touch them with a common sympathy, and to inspire them with a common ideal. It was believed that young students should be quickened in their years of vague aspiration and purely speculative energy by possessing a share in this broad practical work.

Settlement and community houses in the United States were a vital part of the settlement movement, a progressive social movement that began in the mid-19th century in London with the intention of improving the quality of life in poor urban areas through education initiatives, food and shelter provisions, and assimilation and naturalization assistance.

Rivington Street Settlement was an American settlement house which provided educational and social services on the Lower East Side of the Manhattan borough of New York City, New York. Under the auspices of the College Settlements Association (CSA), it focused on the mostly immigrant population of the neighborhood. Originally located at 95 Rivington Street (1889-), other locations later included 96 Rivington Street (1892-1901), 188 Ludlow Street (1902–), 84-86 First Street (1907-), and Summer Home, Mount Ivy, New York (1900-). The Rivington Street Settlement was established by college women, was controlled by college women, and had a majority of college women as residents. The Rivington Street Settlement was a kind of graduate school in economics and sociology, with practical lessons in a tenement–house district - a kind of sociological laboratory.

Jean Gurney Spahr was an American social reformer. A pioneer in the U.S. settlement movement, she was a co-founder and officer of the College Settlements Association (CSA), and the head of the Rivington Street Settlement in New York City.

Orange Valley Social Institute was an American settlement house established during the settlement movement era to provide educational and social opportunities for the people of the neighborhood. It was located close to Newark in The Oranges' hatting district at No. 35 Tompkins street, Orange Valley, New Jersey. Opened April 1, 1897, under the auspices of a committee of citizens of Orange, New Jersey, it was later governed by a Board of Directors of the Settlement Association. It was maintained by private contributions. Head residents included Bryant Venable, The settlement contained a kindergarten, boys' games club, basket weaving club, shuffleboard club, mothers' meetings, chair caning club, bowling club and a library. In the first nine months of 1902, 497 persons borrowed 3,568 books, while there was an average daily attendance of about 30 at the reading rooms.

Goodrich Social Settlement was the second settlement house in Cleveland, Ohio, after Hiram House. It organized on December 9, 1896, incorporated May 15, 1897, and opened May 20, 1897 at Bond St. and St. Clair Ave. It was established by Flora Stone Mather as an outgrowth of a boys' club and women's guild conducted by the First Presbyterian Church. Its aims were “to provide a center for such activities as are commonly associated with Christian social settlement work". It was maintained by an endowment. The Goodrich House Farm, in Euclid Point, Ohio, was part of the settlement.

Alice P. Gannett was an American settlement house worker and social reformer. The Goodrich-Gannett Neighborhood Center in Cleveland, Ohio, is named in her honor.

Neighborhood House was an American settlement house in Chicago, Illinois. It was opened in October 1896, by Samuel S. and Harriet M. Van Der Vaart, under the auspices of the Young People's Society of the Universalist Church, of Englewood, Chicago, and with the assistance of teachers of the Perkins, Bass, and D. S. Wentworth public schools. It was officially established in the Fall of 1897 by Harriet Van Der Vaart as the outgrowth of the kindergarten opened the year before "to bring together for mutual benefit people of different classes and conditions."

Whittier House was an American social settlement, situated in the midst of the densely populated Paulus Hook district of Jersey City, New Jersey. Christian, but non-denominational, its aims were to help all in need by improving their circumstances, by inspiring them with new motives and higher ideals, and by making them better fitted by the responsibilities and privileges of life. It cooperated with all who were seeking to ameliorate the human condition and improve the social order. It opened in the People's Palace, December 20, 1893. On May 14, 1894, it incorporated and moved to 174 Grand Street.

Lawrence House was an American social settlement in Baltimore, Maryland. Its beginnings were in 1893, when Rev. Dr. Edward A. Lawrence and a friend took up lodging at 214 Parkin Street. Lawrence died suddenly later in 1893, and in his memory, the Lawrence Memorial Association organized in 1894 and purchased a house at 816 West Lombard Street. The settlement incorporated in the Fall of 1900. In 1904, the place was enlarged by the addition of the adjoining house, 814 West Lombard Street.

Anna E. Nicholes was an American social reformer, civil servant, and clubwoman associated with women's suffrage and the settlement movement in Chicago. She devoted her life to charitable and philanthropic work.

South Park Settlement was an American settlement movement-era settlement established in the South Park neighborhood of San Francisco, California on January 2, 1895, by the San Francisco Settlement Association. It was founded in one of the crowded districts of San Francisco. The pretty little oval park on which the Settlement House faces was formerly the fashionable residence district of the city. But within a few blocks on either side of South Park were many little streets, whose crowded tenements furnished homes for less prosperous working people. Its goals were to establish and maintain a settlement in San Francisco as a residence for persons interested in the social and moral condition of its neighborhood; to bring into friendly and helpful relations with one another the people of the neighborhood in which the settlement was situated; to cooperate with church, educational, charitable and labor organizations, and with other agencies acting for the improvement of social conditions; to serve as a medium among the different social elements of the city for bringing about a more intelligent and systematic understanding of their mutual obligations; as well as to do social and educational work in the neighborhood; co-operate in the civic work of the city; and investigate social and economic conditions.

Amity Church Settlement was an American settlement house founded in 1896 and auxiliary to Amity Baptist Church. It was located at 314 West 54th Street in the Manhattan borough of New York City, New York. Its purpose included the religious and social well-being of the neighborhood. Services included educational classes, lectures, and poor relief. The director was Rev. Leighton Williams, Pastor. The undenominational spirit and able management of the House attracted confidence and financial assistance from outside Baptist lines. Its basal function was that of establishing residence in the crowded neighborhood where its work lay and bringing to bear upon the labor in hand the influence of the home. It sought to unite the idea of the Church and of the social settlement. The settlement was unincorporated, and was maintained by Amity Baptist Church and by voluntary contributions. The work was classified as (1) religious, including the various church services; (2) educational, including kindergarten, industrial school, evening classes, public lectures under the board of education; (3) medical, including dispensary and nursing work; (4) social, including Workingmen's Institute, social clubs and entertainments; (5) relief work; and (6) neighborhood work, including visitation and all work outside of the building, as well as promotion of neighborhood interests.