The president of Dáil Éireann, later also president of the Irish Republic, was the leader of the revolutionary Irish Republic of 1919–1922. The office was created in the Dáil Constitution adopted by Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Republic, at its first meeting in January 1919. This provided that the president was elected by the Dáil as head of a cabinet called the Ministry of Dáil Éireann. During this period, Ireland was deemed part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in international law, but the Irish Republic had made a unilateral Declaration of Independence on 21 January 1919. On 6 December 1922, after the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Irish Free State was recognised as a sovereign state, and the position of the President of Dáil Éireann was replaced by that of President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State but, as a Dominion of the British Empire, King George V was head of state.

The Oireachtas, sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the bicameral parliament of Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of the President of Ireland and the two houses of the Oireachtas, the Dáil Éireann and the Seanad Éireann.

The Constitution of Ireland is the fundamental law of Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. The constitution, based on a system of representative democracy, is broadly within the tradition of liberal democracy. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executive president, a bicameral parliament, a separation of powers and judicial review.

The Constitution of the Irish Free State was adopted by Act of Dáil Éireann sitting as a constituent assembly on 25 October 1922. In accordance with Article 83 of the Constitution, the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 of the British Parliament, which came into effect upon receiving the royal assent on 5 December 1922, provided that the Constitution would come into effect upon the issue of a Royal Proclamation, which was done on 6 December 1922. In 1937 the Constitution of the Irish Free State was replaced by the modern Constitution of Ireland following a referendum.

The Constitution of Ireland vests executive authority in the Government of Ireland, which is headed by the Taoiseach, the head of government. The government – also known as the cabinet – is composed of ministers, each of whom must be a member of the Oireachtas, which consists of Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann. Most ministers have a portfolio of specific responsibilities such as departments or policy areas, although ministers without portfolio can be appointed.

The Supreme Court of Ireland is the highest judicial authority in Ireland. It is a court of final appeal and exercises, in conjunction with the Court of Appeal and the High Court, judicial review over Acts of the Oireachtas. The Supreme Court also has appellate jurisdiction to ensure compliance with the Constitution of Ireland by governmental bodies and private citizens. It sits in the Four Courts in Dublin.

The Ninth Amendment of the Constitution Act 1984 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland that allowed for the extension of the right to vote in elections to Dáil Éireann to non-Irish citizens. It was approved by referendum on 14 June 1984, the same day as the European Parliament election, and signed into law on 2 August of the same year.

Amendments to the Constitution of Ireland are only possible by way of referendum. A proposal to amend the Constitution of Ireland must first be passed as a bill by both Houses of the Oireachtas (parliament), then submitted to a referendum, and finally signed into law by the President of Ireland. Since the constitution entered into force on 29 December 1937, there have been 32 amendments to the constitution.

An ordinary referendum in Ireland is a referendum on a bill other than a bill to amend the Constitution. The Constitution prescribes the process in Articles 27 and 47. Whereas a constitutional referendum is mandatory for a constitutional amendment bill, an ordinary referendum occurs only if the bill "contains a proposal of such national importance that the will of the people thereon ought to be ascertained". This is decided at the discretion of the President, after a petition by Oireachtas members including a majority of Senators. No such petition has ever been presented, and thus no ordinary referendum has ever been held.

Dáil Éireann served as the directly elected lower house of the Oireachtas of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1937. The Free State constitution described the role of the house as that of a "Chamber of Deputies". Until 1936 the Free State Oireachtas also included an upper house known as the Seanad. Like its modern successor, the Free State Dáil was, in any case, the dominant component of the legislature; it effectively had authority to enact almost any law it chose, and to appoint and dismiss the President of the Executive Council. The Free State Dáil ceased to be with the creation of the modern 'Dáil Éireann' under the terms of the 1937 Constitution of Ireland. Both the Dáil and Seanad sat in Leinster House.

The Oireachtas of the Irish Free State was the legislature of the Irish Free State from 1922 until 1937. It was established by the 1922 Constitution of Ireland which was based from the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It was the first independent Irish Parliament officially recognised outside Ireland since the historic Parliament of Ireland which was abolished with the Acts of Union 1800.

The Credit Institutions Act 2008 is an Act of the Oireachtas. It was emergency legislation passed by the Irish Government on Tuesday, 30 September 2008 and enacted on Thursday, 2 October to provide a €440 billion guarantee to six Irish banks to prevent possible collapse as a result of the Financial crisis of 2007–2008

Seanad Éireann is the upper house of the Oireachtas, which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann.

In Ireland, "publication or utterance of blasphemous matter", defamatory of any religion, was a criminal offence until 17 January 2020. It was a requirement of the 1937 Constitution until removed after a 2018 referendum. The common law offence of blasphemous libel, applicable only to Christianity and last prosecuted in 1855, was believed to fulfil the constitutional requirement until a 1999 ruling that it was incompatible with the constitution's guarantee of religious equality. The Defamation Act 2009 included a provision intended to fill the lacuna while being "virtually impossible" to enforce, and no prosecution was made under it. The 2009 statute increased controversy, with proponents of freedom of speech and freedom of religion arguing for amending the constitution. After the 2018 constitutional amendment, a separate bill to repeal the 2009 provision and residual references to blasphemy was enacted in 2019 by the Oireachtas (parliament) and came into force in 2020. The Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Act 1989, which includes religion among the characteristics protected from incitement to hatred, remains in force.

The Thirty-first Amendment of the Constitution (Children) Act 2012 amended the Constitution of Ireland by inserting clauses relating to children's rights and the right and duty of the state to take child protection measures. It was passed by both Houses of the Oireachtas (parliament) on 10 October 2012, and approved at a referendum on 10 November 2012, by 58% of voters on a turnout of 33.5%. Its enactment was delayed by a High Court case challenging the conduct of the referendum. The High Court's rejection of the challenge was confirmed by the Supreme Court on 24 April 2015. It was signed into law by the President on 28 April 2015.

The Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013 was an Act of the Oireachtas which, until 2018, defined the circumstances and processes within which abortion in Ireland could be legally performed. The act gave effect in statutory law to the terms of the Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court in the 1992 judgment Attorney General v. X. That judgment allowed for abortion where pregnancy endangers a woman's life, including through a risk of suicide. The provisions relating to suicide had been the most contentious part of the bill. Having passed both Houses of the Oireachtas in July 2013, it was signed into law on 30 July by Michael D. Higgins, the President of Ireland, and commenced on 1 January 2014. The 2013 Act was repealed by the Health Act 2018, which commenced on 1 January 2019.

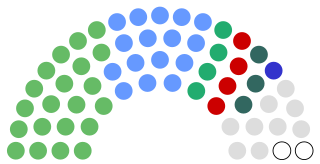

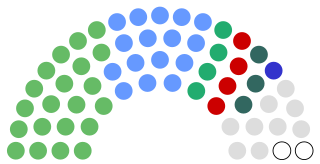

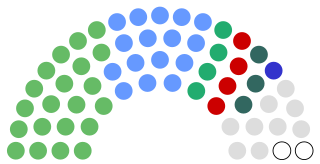

Dáil Éireann is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas, which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann. It consists of 160 members, each known as a Teachta Dála. TDs represent 39 constituencies and are directly elected for terms not exceeding five years, on the system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote (PR-STV). Its powers are similar to those of lower houses under many other bicameral parliamentary systems and it is by far the dominant branch of the Oireachtas. Subject to the limits imposed by the Constitution of Ireland, it has power to pass any law it wishes, and to nominate and remove the Taoiseach. Since 1922, it has met in Leinster House in Dublin.

The Thirty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland which altered the provisions regulating divorce. It removed the constitutional requirement for a defined period of separation before a Court may grant a dissolution of marriage, and eased restrictions on the recognition of foreign divorces. The amendment was effected by an act of the Oireachtas, the Thirty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution Act 2019.

Sivsivadze v Minister for Justice[2015] IESC 53; [2015] 2 ILRM 73; [2016] 2 IR 403 was an Irish Supreme Court case in which the Supreme Court dismissed a challenge to the constitutionality of section 3(1) of the Immigration Act 1999, under which the Minister for Justice order the deportation of a non-national for an indefinite period.

Benedict McGowan and Others v Labour Court and Others [2013] 2 ILRM 276; [2013] IESC 21; [2013] 3 IR 718 is an Irish Supreme Court case, where an appeal was granted and the court made a declaration that the provisions of Part III of the Industrial Relations Act are invalid considering the provisions of Article 15.2.1 of the Constitution of Ireland. This court questioned the method by which wages and other benefits were set on a collective basis across numerous sectors.