New England cuisine is an American cuisine which originated in the New England region of the United States, and traces its roots to traditional English cuisine and Native American cuisine of the Abenaki, Narragansett, Niantic, Wabanaki, Wampanoag, and other native peoples. It also includes influences from Irish, French-Canadian, Italian, and Portuguese cuisine, among others. It is characterized by extensive use of potatoes, beans, dairy products and seafood, resulting from its historical reliance on its seaports and fishing industry. Corn, the major crop historically grown by Native American tribes in New England, continues to be grown in all New England states, primarily as sweet corn although flint corn is grown as well. It is traditionally used in hasty puddings, cornbreads and corn chowders.

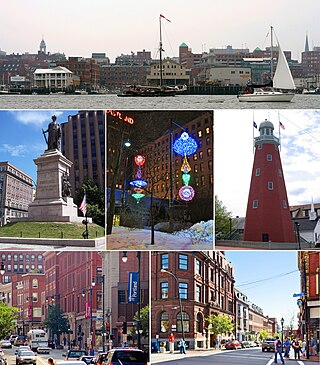

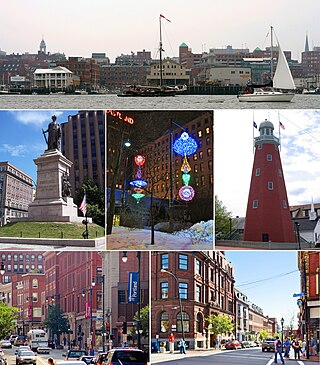

Portland is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area has a population of approximately 550,000 people. Historically tied to commercial shipping, the marine economy, and light industry, Portland's economy in the 21st century relies mostly on the service sector. The Port of Portland is the second-largest tonnage seaport in the New England area as of 2019.

The University of Southern Maine (USM) is a public university with campuses in Portland, Gorham and Lewiston, Maine, United States. It is the southernmost of the University of Maine System. It was founded as two separate state universities, Gorham Normal School and Portland University. The two universities, later known as Gorham State College and the University of Maine at Portland, were combined in 1970 to help streamline the public university system in Maine and eventually expanded by adding the Lewiston campus in 1988.

A ploye or ployes are a Brayon flatbread type mix of buckwheat flour, wheat flour, baking powder and water which is extremely popular in the Madawaska region in New Brunswick and Maine.

A vegetarian hot dog is a hot dog produced completely from non-meat products. Unlike traditional home-made meat sausages, the casing is not made of intestine, but of cellulose or other plant-based ingredients. The filling is usually based on some sort of soy protein, wheat gluten, or pea protein. Some may contain egg whites, which would make them unsuitable for a lacto-vegetarian or vegan diet.

The Maine Italian sandwich, or Italian, is a submarine sandwich in Italian-American cuisine. The Maine Italian sandwich was invented in Portland, Maine.

Helen Knothe Nearing was an American author, advocate of simple living and a lifelong vegetarian.

The Portland Farmers Market is a farmers market in Portland, Maine, U.S., which has been in continuous operation since 1768. Since 1990, the market has been held place year-round. From May to November, it is held on Wednesdays in Monument Square and on Saturdays in Deering Oaks Park. From December to April, the winter market is held on Saturdays in the former Catherine McAuley High School building.

The North American Vegetarian Society (NAVS) is a charity and activist organization with the stated objectives of supporting vegetarians and informing the public about the benefits of vegetarianism.

The Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA) certifies organic food and products throughout the State of Maine. It is a voluntary organization whose office is located in Unity, Maine. As of 2016, MOFGA certifies 480 producers and growers.

Freya Smith Dinshah is the author of The Vegan Kitchen, president of the American Vegan Society in Malaga, New Jersey, and editor of American Vegan magazine.

Toni Fiore is an American TV host, cookbook author, and chef, focusing on vegetarian and vegan dishes.

Avery Yale Kamila is an American journalist and community organizer in the state of Maine. Kamila has written a food column for the Portland Press Herald /Maine Sunday Telegram and its affiliated newspapers since 2009.

Will Bonsall is an American author, seed saver and veganic farmer who lives in Maine. He is a regular speaker about seed saving, organic farming and veganic farming.

A vegan school meal or vegan school lunch or vegan school dinner or vegan hot lunch is a vegan option provided as a school meal. A small number of schools around the world serve vegan food or are vegan schools, serving exclusively vegan food.

Horace A. Barrows was an American physician who practiced in Western Maine in the early 19th century, made and sold plant-based medicines, prescribed a vegetarian diet and invested in local businesses.

The Green Elephant Vegetarian Bistro is a vegetarian restaurant serving Thai cuisine in Portland, Maine, that opened in 2007 in the city's Arts District. A second Green Elephant restaurant is located in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Both have received critical attention for their vegetarian dishes.

Henry Aiken Worcester was a Yale University alumnus, a vegetarian, and a Swedenborgian minister who worked in Maine and Massachusetts. His "Sermons on the Lord's Prayer" was published posthumously in 1850.

The Hollow Reed was a vegetarian restaurant in the Old Port district of Portland, Maine. It opened on February 7, 1974, and closed in 1981, and is cited for its influence on the city's notable restaurant culture.

The Great Lost Bear is a bar and restaurant at 540 Forest Avenue in Portland, Maine, United States. Established in 1979 by Dave and Weslie Evans and Chip MacConnell, it is noted for its selection of draft craft beers.