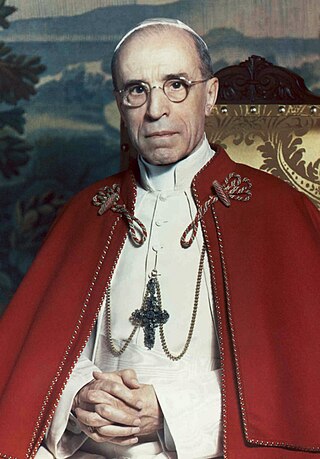

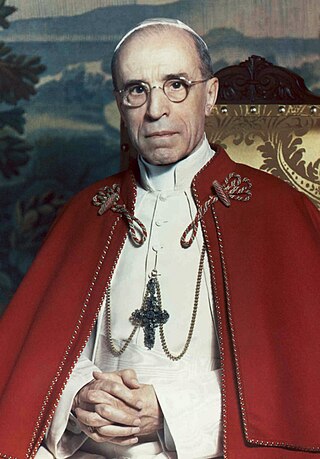

Pope Pius XII was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his election to the papacy, he served as secretary of the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, papal nuncio to Germany, and Cardinal Secretary of State, in which capacity he worked to conclude treaties with various European and Latin American nations, including the Reichskonkordat treaty with the German Reich.

The Lateran Treaty was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle the long-standing Roman Question. The treaty and associated pacts were named after the Lateran Palace where they were signed on 11 February 1929, and the Italian parliament ratified them on 7 June 1929. The treaty recognised Vatican City as an independent state under the sovereignty of the Holy See. The Italian government also agreed to give the Roman Catholic Church financial compensation for the loss of the Papal States. In 1948, the Lateran Treaty was recognized in the Constitution of Italy as regulating the relations between the state and the Catholic Church. The treaty was significantly revised in 1984, ending the status of Catholicism as the sole state religion.

Pope Pius XI, born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was the Bishop of Rome and supreme pontiff of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to 10 February 1939. He also became the first sovereign of Vatican City upon its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929 where he held that position in addition to being the earthly leader of the Catholic Church until his death in February 1939. He assumed as his papal motto "Pax Christi in Regno Christi", translated "The Peace of Christ in the Kingdom of Christ".

Prince Adam Stefan Stanisław Bonifacy Józef Cardinal Sapieha was a senior-ranking Polish prelate of the Catholic Church who served as Archbishop of Kraków from 1911 to 1951. Between 1922 and 1923, he was a senator of the Second Polish Republic. In 1946, Pope Pius XII created him a Cardinal.

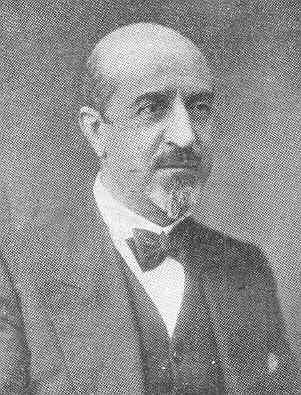

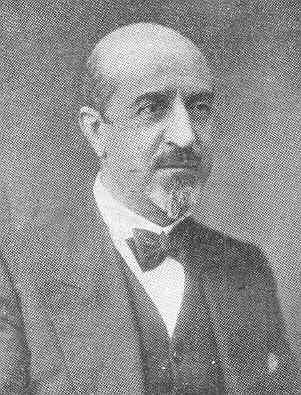

Pietro Gasparri was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and Pope Pius XI.

Adolf Bertram was archbishop of Breslau and a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

The Catholic Church in Lithuania is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome. Lithuania is the world's northernmost Catholic majority country. Pope Pius XII gave Lithuania the title of "northernmost outpost of Catholicism in Europe" in 1939.

Stanisław Grabski was a Polish economist and politician associated with the National Democracy political camp. As the top Polish negotiator during the Peace of Riga talks in 1921, Grabski greatly influenced the future of Poland and the Soviet Union.

The Diocese of Chełmno was a Catholic diocese in Chełmno Land, founded in 1243 and disbanded in 1992.

The 1926 Lithuanian coup d'état was a military coup d'état in Lithuania that replaced the democratically elected government with a nationalist regime led by Antanas Smetona. The coup took place on 17 December 1926 and was largely organized by the military; Smetona's role remains the subject of debate. The coup brought the Lithuanian Nationalist Union, the most conservative party at the time, to power. Previously it had been a fairly new and insignificant nationalistic party. By 1926, its membership reached about 2,000 and it had won only three seats in the parliamentary elections. The Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party, the largest party in the Seimas at the time, collaborated with the military and provided constitutional legitimacy to the coup, but accepted no major posts in the new government and withdrew in May 1927. After the military handed power over to the civilian government, it ceased playing a direct role in political life.

The Third Seimas of Lithuania was the third parliament (Seimas) democratically elected in Lithuania after it declared independence on 16 February 1918. The elections took place on 8–10 May 1926. For the first time the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party were forced to remain in opposition. The coalition government made some unpopular decisions and was sharply criticized. Regular Seimas work was interrupted by a military coup d'état in December 1926 when the democratically elected government was replaced with the authoritarian government of Antanas Smetona and Augustinas Voldemaras. The Third Seimas was dissolved on 12 March 1927 and new elections were not called until 1936.

Persecutions against the Catholic Church took place during the papacy of Pope Pius XII (1939–1958). Pius' reign coincided with World War II (1939–1945), followed by the commencement of the Cold War and the accelerating European decolonisation. During his papacy, the Catholic Church faced persecution under Fascist and Communist governments.

Pope Pius XII and Poland includes Church relations from 1939 to 1958. Pius XII became Pope on the eve of the Second World War. The invasion of predominantly Catholic Poland by Nazi Germany in 1939 ignited the conflict and was followed soon after by a Soviet invasion of the Eastern half of Poland, in accordance with an agreement reached between the dictators Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler. The Catholic Church in Poland was about to face decades of repression, both at Nazi and Communist hands. The Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church in Poland was followed by a Stalinist repression which was particularly intense through the years 1946–1956. Pope Pius XII's policies consisted in attempts to avoid World War II, extensive diplomatic activity on behalf of Poland and encouragement to the persecuted clergy and faithful.

Pope Pius IX and Russia includes the relations between the Pontiff and the Russian Empire during the years 1846–1878.

Francesco Pacelli was an Italian lawyer and the elder brother of Eugenio Pacelli, who would later become Pope Pius XII. He acted as a legal advisor to Pope Pius XI; in this capacity, he assisted Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Gasparri in the negotiation of the Lateran Treaty, which established the independence of Vatican City.

The reorganization of occupied dioceses during World War II was an issue faced by Pope Pius XII of whether to extend the apostolic authority of Catholic bishops from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy to German-occupied Europe during World War II.

The 1847 Agreement between the Holy See and the Russian Empire was a diplomatic arrangement entered into on 3 August of that year.

The relationship between Pope Pius XI and Poland is often considered to have been good, as Church life in Poland flourished during his pontificate.

Holy See–Poland relations are foreign relations between the Holy See and the Republic of Poland. As of 2015, approximately 92.9 percent of Poles belong to the Catholic Church.

The Most Holy Virgin Mary, Queen of Poland is an honorary title for Mary, mother of Jesus, used by Polish Catholics.