The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of commercial farming and livestock food production, promotes agricultural trade and production, works to assure food safety, protects natural resources, fosters rural communities and works to end hunger in the United States and internationally. It is headed by the Secretary of Agriculture, who reports directly to the President of the United States and is a member of the president's Cabinet. The current secretary is Tom Vilsack, who has served since February 24, 2021.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) is a public policy research institute of the United States Congress. Operating within the Library of Congress, it works primarily and directly for members of Congress and their committees and staff on a confidential, nonpartisan basis. CRS is sometimes known as Congress' think tank due to its broad mandate of providing research and analysis on all matters relevant to national policymaking.

Seed companies produce and sell seeds for flowers, fruits and vegetables to commercial growers and amateur gardeners. The production of seed is a multibillion-dollar business, which uses growing facilities and growing locations worldwide. While most of the seed is produced by large specialist growers, large amounts are also produced by small growers that produce only one to a few crop types. The larger companies supply seed both to commercial resellers and wholesalers. The resellers and wholesalers sell to vegetable and fruit growers, and to companies who package seed into packets and sell them on to the amateur gardener.

The National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) is the statistical branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System. NASS has 12 regional offices throughout the United States and Puerto Rico and a headquarters unit in Washington, D.C. NASS conducts hundreds of surveys and issues nearly 500 national reports each year on issues including agricultural production, economics, demographics and the environment. NASS also conducts the United States Census of Agriculture every five years.

The Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) is an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture; it maintains programs in five commodity areas: cotton and tobacco; dairy; fruit and vegetable; livestock and seed; and poultry. These programs provide testing, standardization, grading and market news services for those commodities, and oversee marketing agreements and orders, administer research and promotion programs, and purchase commodities for federal food programs. The AMS enforces certain federal laws such as the Perishable Agricultural Commodities Act and the Federal Seed Act. The AMS budget is $1.2 billion. It is headquartered in the Jamie L. Whitten Building in Washington, D.C.

The Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) is a wholly owned United States government corporation that was created in 1933 to "stabilize, support, and protect farm income and prices". The CCC is authorized to buy, sell, lend, make payments, and engage in other activities for the purpose of increasing production, stabilizing prices, assuring adequate supplies, and facilitating the efficient marketing of agricultural commodities.

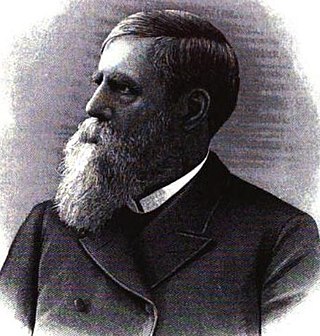

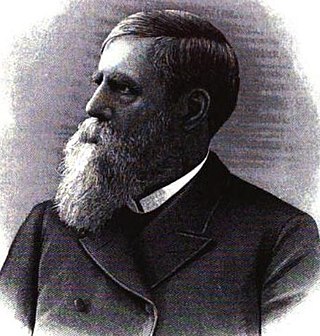

Edwin Willits (also Willets) (April 24, 1830 – October 22, 1896) was a politician from the U.S. state of Michigan. Willits served as prosecuting attorney of Monroe County, Republican from Michigan's 2nd congressional district for the 45th, 46th, and 47th Congresses. Presidents of Michigan State Normal School (now Eastern Michigan University) and the State Agricultural College (now Michigan State University). The first Assistant U.S. Secretary of Agriculture under Jeremiah McLain Rusk for Benjamin Harrison's administration.

In the United States, the Child Nutrition Programs are a grouping of programs funded by the federal government to support meal and milk service programs for children in schools, residential and day care facilities, family and group day care homes, and summer day camps, and for low-income pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and children under age 5 in local WIC clinics.

The Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) is a program that evolved out of surplus commodity donation efforts begun by the USDA in late 1981 to dispose of surplus foods held by the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). This program was explicitly authorized by the Congress in 1983 when funding was provided to assist states with the costs involved in storing and distributing the commodities. The program originally was entitled the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program when authorized under the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Act of 1983. The program is now known as The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP).

The Food Security Act of 1985, a 5-year omnibus farm bill, allowed lower commodity price and income supports and established a dairy herd buyout program. This 1985 farm bill made changes in a variety of other USDA programs. Several enduring conservation programs were created, including sodbuster, swampbuster, and the Conservation Reserve Program.

The Federal Seed Act, P.L. 76-354, requires accurate labeling and purity standards for seeds in commerce, and prohibits the importation and movement of adulterated or misbranded seeds. The law works in conjunction with the Plant Protection Act of 2000 to authorize the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to regulate the importation of field crop, pasture and forage, or vegetable seed that may contain noxious weed seeds. USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service is responsible for enforcing the labeling and purity standard provisions.

The Office of Seed and Plant Introduction was the first official branch of the United States Department of Agriculture responsible for collecting and introducing new plant species and varieties to the United States. It was established in 1898, under the direction of David Fairchild and employed agricultural explorers to seek out economically useful plants to introduce to the United States from all over the world. It has introduced over 200,000 species and varieties of non-native plants to the United States including some of the most well-known and economically significant crops. The Office of Seed and Plant Introduction's activities are largely responsible for the industrialization of agriculture in the United States. Since the establishment of the Office of Seed and Plant Introduction there has been an office within the USDA with this responsibility, though its name changes periodically. Today, the branch of the USDA responsible for collecting and introducing new plant species is called the National Germplasm Resources Laboratory.

The U.S. National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) is a network of institutions and agencies led by the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the effort to conserve and facilitate the use of the genetic diversity of agriculturally important plants and their wild relatives.

The Farmer Assurance Provision refers to Section 735 of US H.R. 933, a bill that was passed by the Senate on March 20, 2013, and then signed into law as part of the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2013 by President Barack Obama on March 26, 2013. The provisions of this law remained in effect for six months, until the end of the fiscal year on September 30, 2013. The Farmer Assurance Provision was discontinued in Sec. 101 of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014. The bill is commonly referred to as the "Monsanto Protection Act" by its critics.

The Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES) was an extension agency within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), part of the executive branch of the federal government. The 1994 Department Reorganization Act, passed by Congress, created CSREES by combining the former Cooperative State Research Service and the Extension Service into a single agency.

The Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2015 is an appropriations bill for fiscal year 2015 that would provide funding for the United States Department of Agriculture and related agencies. The bill would appropriate $20.9 billion.

Farmers' Bulletin was published by the United States Department of Agriculture with the first issue appearing in June 1889. The farm bulletins could be obtained upon the written request to a Member of Congress or to the United States Secretary of Agriculture. The agricultural circular would be sent complimentary to any address within the United States. The agricultural publication covered an extensive range of rural topics as related to agricultural science, agronomy, plant diseases, rural living, soil conservation, and sustainable agriculture.

Agricultural Experiment Stations Act of 1887 is a United States federal statute establishing agricultural research by the governance of the United States land-grant colleges as enacted by the Land-Grant Agricultural and Mechanical College Act of 1862. The agricultural experiment station alliance was granted fiscal appropriations by the enactment of the Hatch Act of 1887. The Act of Congress defines the basis of the agricultural experiments and scientific research by the State or Territory educational institutions.

The 2018 farm bill or Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 is an enacted United States farm bill that reauthorized $867 billion for many expenditures approved in the prior farm bill. The bill was passed by the Senate and House on December 11 and 12, 2018, respectively. On December 20, 2018, it was signed into law by President Donald Trump.

Arlington Experimental Farm was a former federal agricultural research farm in Alexandria, Virginia that opened in 1900. It was established by an Act of Congress, moving the Department of Agriculture's main research from the National Mall to Arlington. It grew hemp beginning in 1903, or 1914. In 1928, it was the largest United States Department of Agriculture experiment station in the Washington, D.C. area. USDA researcher Vera Charles also worked at the station, collecting Cannabis seeds from across America and studying pests and pathogens that could diminish hemp crop productivity. Cultivars developed at Arlington include Arlington, Chington, Ferramington, Kymington and Arlington; Chington and Kymington were adopted "extensively" by seed farmers producing hemp in Kentucky. The seeds were probably destroyed by the government in the 1980s.