Related Research Articles

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics focuses on the study of individual markets, sectors, or industries as opposed to the national economy as a whole, which is studied in macroeconomics.

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption, and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good or service is determined through a hypothetical maximization of utility by income-constrained individuals and of profits by firms facing production costs and employing available information and factors of production. This approach has often been justified by appealing to rational choice theory.

In economics, utility is a measure of the satisfaction that a certain person has from a certain state of the world. Over time, the term has been used in two different meanings.

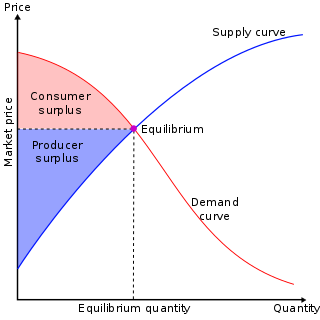

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus, is either of two related quantities:

Consumerism is a social and economic order in which the goals of many individuals include the acquisition of goods and services beyond those that are necessary for survival or for traditional displays of status. Consumerism has historically existed in many societies, with modern consumerism originating in Western Europe before the Industrial Revolution and becoming widespread around 1900. In 1899, a book on consumerism published by Thorstein Veblen, called The Theory of the Leisure Class, examined the widespread values and economic institutions emerging along with the widespread "leisure time" at the beginning of the 20th century. In it, Veblen "views the activities and spending habits of this leisure class in terms of conspicuous and vicarious consumption and waste. Both relate to the display of status and not to functionality or usefulness."

In economics, capital goods or capital are "those durable produced goods that are in turn used as productive inputs for further production" of goods and services. A typical example is the machinery used in a factory. At the macroeconomic level, "the nation's capital stock includes buildings, equipment, software, and inventories during a given year."

The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption, by maximizing utility subject to a consumer budget constraint. Factors influencing consumers' evaluation of the utility of goods include: income level, cultural factors, product information and physio-psychological factors.

Human Action: A Treatise on Economics is a work by the Austrian economist and philosopher Ludwig von Mises. Widely considered Mises' magnum opus, it presents the case for laissez-faire capitalism based on praxeology, his method to understand the structure of human decision-making. Mises rejected positivism within economics, and defended an a priori foundation for praxeology, as well as methodological individualism and laws of self-evident certainty. Mises argues that the free-market economy not only outdistances any government-planned system, but ultimately serves as the foundation of civilization itself.

Welfare economics is a field of economics that applies microeconomic techniques to evaluate the overall well-being (welfare) of a society. This evaluation is typically done at the economy-wide level, and attempts to assess the distribution of resources and opportunities among members of society.

Allocative efficiency is a state of the economy in which production is aligned with the preferences of consumers and producers; in particular, the set of outputs is chosen so as to maximize the social welfare of society. This is achieved if every produced good or service has a marginal benefit equal to the marginal cost of production.

Consumption is the act of using resources to satisfy current needs and wants. It is seen in contrast to investing, which is spending for acquisition of future income. Consumption is a major concept in economics and is also studied in many other social sciences.

In economics, goods are items that satisfy human wants and provide utility, for example, to a consumer making a purchase of a satisfying product. A common distinction is made between goods which are transferable, and services, which are not transferable.

In microeconomics, the law of demand is a fundamental principle which states that there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. In other words, "conditional on all else being equal, as the price of a good increases (↑), quantity demanded will decrease (↓); conversely, as the price of a good decreases (↓), quantity demanded will increase (↑)". Alfred Marshall worded this as: "When we say that a person's demand for anything increases, we mean that he will buy more of it than he would before at the same price, and that he will buy as much of it as before at a higher price". The law of demand, however, only makes a qualitative statement in the sense that it describes the direction of change in the amount of quantity demanded but not the magnitude of change.

Man, Economy, and State: A treatise on economic principles is a 1962 book of Austrian School economics by Murray Rothbard.

Dollar voting is an analogy that refers to the theoretical impact of consumer choice on producers' actions by means of the flow of consumer payments to producers for their goods and services.

Buddhist economics is a spiritual and philosophical approach to the study of economics. It examines the psychology of the human mind and the emotions that direct economic activity, in particular concepts such as anxiety, aspirations and self-actualization principles. In the view of its proponents, Buddhist economics aims to clear the confusion about what is harmful and what is beneficial in the range of human activities involving the production and consumption of goods and services, ultimately trying to make human beings ethically mature. The ideology's stated purpose is to "find a middle way between a purely mundane society and an immobile, conventional society."

In macroeconomics, a general glut is an excess of supply in relation to demand, specifically, when there is more production in all fields of production in comparison with what resources are available to consume (purchase) said production. This exhibits itself in a general recession or depression, with high and persistent underutilization of resources, notably unemployment and idle factories. The Great Depression is often cited as an archetypal example of a general glut.

In any technical subject, words commonly used in everyday life acquire very specific technical meanings, and confusion can arise when someone is uncertain of the intended meaning of a word. This article explains the differences in meaning between some technical terms used in economics and the corresponding terms in everyday usage.

The economics concept of a merit good, originated by Richard Musgrave, is a commodity which is judged that an individual or society should have on the basis of some concept of benefit, rather than ability and willingness to pay. The term is, perhaps, less often used presently than it was during the 1960s to 1980s but the concept still motivates many economic actions by governments. Examples include in-kind transfers such as the provision of food stamps to assist nutrition, the delivery of health services to improve quality of life and reduce morbidity, and subsidized housing and education.

This glossary of economics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in economics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields.

References

- 1 2 Sirgy, M. Joseph; Lee, Dong-Jin; Yu, Grace B. (1 July 2011). "Consumer Sovereignty in Healthcare: Fact or Fiction?". Journal of Business Ethics. 101 (3): 459–474. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0733-5. ISSN 0167-4544. S2CID 154693000.

- ↑ "Consumer sovereignty". www.tutor2u.net. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ↑ Hutt, William H. (1936). Economists and the Public: A Study of Competition and Opinion. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 257.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Persky, Joseph (Winter 1993). "Retrospectives: Consumer Sovereignty". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 7 (1): 183–191. doi:10.1257/jep.7.1.183. JSTOR 2138329.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hutt, William H. (March 1940). "The Concept of Consumers' Sovereignty". The Economic Journal. 50 (197): 66–77. doi:10.2307/2225739. JSTOR 2225739.

- ↑ Mieczkowski, Bogdan (1975). Personal and Social Consumption in Eastern Europe: Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and East Germany. Volume 200 of Praeger special studies in international economics and development. Praeger Publishers. p. 9. ISBN 9780275056209 . Retrieved 20 August 2023.

The 'trial of the Central Statistical Office' in Poland in February 1948, which became the harbinger of Stalinization, featured accusations that the non-Communist Party staff in that office accepted the primacy of consumption. To the Communists this seemed, at the time, an unpardonable transgression, and the 'trial' - held in the form of a two-day public debate - resulted in a wholesale reorganization of the Central Statistical Office and the removal of the offending staff members.

- 1 2 Pearce, David W. (1992). Macmillan Dictionary of Modern Economics.

- ↑ Lerner, Abba P. (1972). "The Economics and Politics of Consumer Sovereignty". The American Economic Review. 62 (1/2): 258–266. ISSN 0002-8282. JSTOR 1821551.

- 1 2 Waldfogel, Joel (1 November 2005). "Does Consumer Irrationality Trump Consumer Sovereignty?". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 87 (4): 691–696. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.670.827 . doi:10.1162/003465305775098107. ISSN 0034-6535. S2CID 37775377.

- ↑ Cunha, Jesse M. (1 April 2014). "Testing Paternalism: Cash versus In-Kind Transfers". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 6 (2): 195–230. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.716.3321 . doi:10.1257/app.6.2.195. ISSN 1945-7782. S2CID 17159709.

- ↑ Thurow, Lester C. (1974). "Cash Versus In-Kind Transfers". The American Economic Review. 64 (2): 190–195. ISSN 0002-8282. JSTOR 1816041.