Related Research Articles

Coitus interruptus, also known as withdrawal, pulling out or the pull-out method, is a method of birth control in which a man, during sexual intercourse, withdraws his penis from a woman's vagina prior to ejaculation and then directs his ejaculate (semen) away from the vagina in an effort to avoid insemination.

Emergency contraception (EC) is a birth control measure, used after sexual intercourse to prevent pregnancy.

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marital situation, career or work considerations, financial situations. If sexually active, family planning may involve the use of contraception and other techniques to control the timing of reproduction.

Levonorgestrel is a hormonal medication which is used in a number of birth control methods. It is combined with an estrogen to make combination birth control pills. As an emergency birth control, sold under the brand names Plan B One-Step and Julie, among others, it is useful within 72 hours of unprotected sex. The more time that has passed since sex, the less effective the medication becomes, and it does not work after pregnancy (implantation) has occurred. Levonorgestrel works by preventing ovulation or fertilization from occurring. It decreases the chances of pregnancy by 57 to 93%. In an intrauterine device (IUD), such as Mirena among others, it is effective for the long-term prevention of pregnancy. A levonorgestrel-releasing implant is also available in some countries.

Hormonal contraception refers to birth control methods that act on the endocrine system. Almost all methods are composed of steroid hormones, although in India one selective estrogen receptor modulator is marketed as a contraceptive. The original hormonal method—the combined oral contraceptive pill—was first marketed as a contraceptive in 1960. In the ensuing decades many other delivery methods have been developed, although the oral and injectable methods are by far the most popular. Hormonal contraception is highly effective: when taken on the prescribed schedule, users of steroid hormone methods experience pregnancy rates of less than 1% per year. Perfect-use pregnancy rates for most hormonal contraceptives are usually around the 0.3% rate or less. Currently available methods can only be used by women; the development of a male hormonal contraceptive is an active research area.

Contraception was illegal in Ireland from 1935 until 1980, when it was legalised with strong restrictions, later loosened. The ban reflected Catholic teachings on sexual morality.

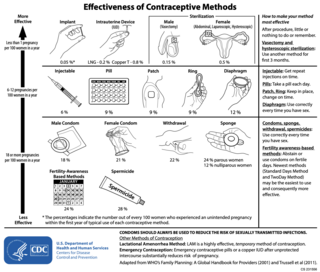

There are many methods of birth control that vary in requirements, side effects, and effectiveness. As the technology, education, and awareness about contraception has evolved, new contraception methods have been theorized and put in application. Although no method of birth control is ideal for every user, some methods remain more effective, affordable or intrusive than others. Outlined here are the different types of barrier methods, hormonal methods, various methods including spermicides, emergency contraceptives, and surgical methods and a comparison between them.

This table includes a list of countries by emergency contraceptive availability.

Contraceptive security is an individual's ability to reliably choose, obtain, and use quality contraceptives for family planning and the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. The term refers primarily to efforts undertaken in low and middle-income countries to ensure contraceptive availability as an integral part of family planning programs. Even though there is a consistent increase in the use of contraceptives in low, middle, and high-income countries, the actual contraceptive use varies in different regions of the world. The World Health Organization recognizes the importance of contraception and describes all choices regarding family planning as human rights. Subsidized products, particularly condoms and oral contraceptives, may be provided to increase accessibility for low-income people. Measures taken to provide contraceptive security may include strengthening contraceptive supply chains, forming contraceptive security committees, product quality assurance, promoting supportive policy environments, and examining financing options.

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unintended pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only became available in the 20th century. Planning, making available, and using human birth control is called family planning. Some cultures limit or discourage access to birth control because they consider it to be morally, religiously, or politically undesirable.

Family planning in India is based on efforts largely sponsored by the Indian government. From 1965 to 2009, contraceptive usage has more than tripled and the fertility rate has more than halved, but the national fertility rate in absolute numbers remains high, causing concern for long-term population growth. India adds up to 1,000,000 people to its population every 20 days. Extensive family planning has become a priority in an effort to curb the projected population of two billion by the end of the twenty-first century.

The birth control movement in the United States was a social reform campaign beginning in 1914 that aimed to increase the availability of contraception in the U.S. through education and legalization. The movement began in 1914 when a group of political radicals in New York City, led by Emma Goldman, Mary Dennett, and Margaret Sanger, became concerned about the hardships that childbirth and self-induced abortions brought to low-income women. Since contraception was considered to be obscene at the time, the activists targeted the Comstock laws, which prohibited distribution of any "obscene, lewd, and/or lascivious" materials through the mail. Hoping to provoke a favorable legal decision, Sanger deliberately broke the law by distributing The Woman Rebel, a newsletter containing a discussion of contraception. In 1916, Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, but the clinic was immediately shut down by police, and Sanger was sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Birth control in the United States is available in many forms. Some of the forms available at drugstores and some retail stores are male condoms, female condoms, sponges, spermicides, and over-the-counter emergency contraception. Forms available at pharmacies with a doctor's prescription or at doctor's offices are oral contraceptive pills, patches, vaginal rings, diaphragms, shots/injections, cervical caps, implantable rods, and intrauterine devices (IUDs). Sterilization procedures, including tubal ligations and vasectomies, are also performed.

Reproductive coercion is a collection of behaviors that interfere with decision-making related to reproductive health. These behaviors are meant to maintain power and control related to reproductive health by a current, former, or hopeful intimate or romantic partner, but they can also be perpetrated by parents or in-laws. Coercive behaviors infringe on individuals' reproductive rights and reduce their reproductive autonomy.

Friends of UNFPA is a non-profit organization, headquartered in New York, that supports the work of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the sexual and reproductive health and rights agency of the United Nations. Friends of UNFPA advances UNFPA's work by mobilizing funds and action for the organization.

Dame Margaret June Sparrow is a New Zealand medical doctor, reproductive rights advocate, and author.

Women's reproductive health in the United States refers to the set of physical, mental, and social issues related to the health of women in the United States. It includes the rights of women in the United States to adequate sexual health, available contraception methods, and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases. The prevalence of women's health issues in American culture is inspired by second-wave feminism in the United States. As a result of this movement, women of the United States began to question the largely male-dominated health care system and demanded a right to information on issues regarding their physiology and anatomy. The U.S. government has made significant strides to propose solutions, like creating the Women's Health Initiative through the Office of Research on Women's Health in 1991. However, many issues still exist related to the accessibility of reproductive healthcare as well as the stigma and controversy attached to sexual health, contraception, and sexually transmitted diseases.

There are many types of contraceptive methods available in France. All contraceptives are obtained by medical prescription after a visit to the family planning, a gynecologist or a midwife. With the exception of emergency contraception that does not require a prescription and can be obtained directly in a pharmacy.

International family planning programs aim to provide women around the world, especially in developing countries, with contraceptive and reproductive services that allow them to avoid unintended pregnancies and control their reproductive choices.

Contraception in Francoist Spain (1939–1975) and the democratic transition (1975–1985) was illegal. It could not be used, sold or covered in information for dissemination. This was partly a result of Hispanic Eugenics that drew on Catholicism and opposed abortion, euthanasia and contraception while trying to create an ideologically aligned population from birth. A law enacted in 1941 saw usage, distribution and sharing of information about contraception become a criminal offense. Midwives were persecuted because of their connections to sharing contraceptive and abortion information with other women. Condoms were somewhat accessible in the Francoist period despite prohibitions against them, though they were associated with men and prostitutes. Other birth control practices were used in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s including diaphragms, coitus interruptus, the pill, and the rhythm method. Opposition to the decriminalization of contraception became much more earnest in the mid-1960s. By 1965, over 2 million units of the pill had been sold in Spain where it had been legal under certain medical conditions since the year before. Despite the Government welcoming the drop in the number of single mothers, they noted in 1975 that this was a result of more women using birth control and seeking abortions abroad.

References

- ↑ Smyth, Helen (2000). Rocking the cradle : contraception, sex, and politics in New Zealand. Wellington, N.Z.: Steele Roberts Ltd. p. 210. ISBN 1-877228-16-8.

- 1 2 "Family planning | UNFPA – United Nations Population Fund". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Sexual & reproductive health | UNFPA – United Nations Population Fund". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- 1 2 "CEDAW | National Council of Women of New Zealand". www.ncwnz.org.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "CEDAW 29th Session 30 June to 25 July 2003". www.un.org. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "CEDAW Concluding Observations" (PDF). Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "5. – Contraception and sterilisation – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". www.teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Smyth, Helen (2000). Rocking the cradle : contraception, sex, and politics in New Zealand. Wellington, N.Z.: Steele Roberts Ltd. p. 81. ISBN 1-877228-16-8.

- 1 2 "The Pill – Family Planning". www.familyplanning.org.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Smyth, Helen (2000). Rocking the cradle : contraception, sex, and politics in New Zealand. Wellington, N.Z.: Steele Roberts Ltd. p. 106. ISBN 1-877228-16-8.

- ↑ Smyth, Helen (2000). Rocking the cradle : contraception, sex, and politics in New Zealand. Wellington, N.Z.: Steele Roberts Ltd. p. 124. ISBN 1-877228-16-8.

- ↑ Smyth, Helen (2000). Rocking the cradle : contraception, sex, and politics in New Zealand. Wellington, N.Z.: Steele Roberts Ltd. p. 223. ISBN 1-877228-16-8.

- ↑ Pool, Ian (1999). New Zealand's contraceptive revolutions. Hamilton: Population Studies Centre, Univ. of Waikato. p. 122. ISBN 1-877149-99-3.

- ↑ "Special Needs Grant Long Acting Reversible Contraception – Work and Income". www.workandincome.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "3. – Contraception and sterilisation – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". www.teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Contraception For Young Women – Family Planning". www.familyplanning.org.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Act 1977 No 112 (as at 01 July 2013), Public Act 3 Sale or disposal, etc, of contraceptives to children [Repealed] – New Zealand Legislation". www.legislation.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Combined Oral Contraceptives – Pharmaceutical Schedule Online". Pharmaceutical Management Agency. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Progestogen-only Contraceptives – Pharmaceutical Schedule Online". Pharmaceutical Management Agency. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Comparing The Cost of Contraception – Family Planning". www.familyplanning.org.nz. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Pill may go over-the-counter". Stuff. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Smyth, Helen (2000). Rocking the cradle : contraception, sex, and politics in New Zealand. Wellington, N.Z.: Steele Roberts Ltd. p. 143. ISBN 1-877228-16-8.

- ↑ "Campaigner welcomes Mirena announcement".

- ↑ Pool, Ian (1999). New Zealand's contraceptive revolutions. Hamilton: Population Studies Centre, Univ. of Waikato. p. 87. ISBN 1-877149-99-3.

- ↑ Skegg, Peter; Paterson, Ron (2015). Health Law in New Zealand. Wellington: Thomson Reuters. p. 591. ISBN 978-0-86472-943-9.