Masonry is the craft of building a structure with brick, stone, or similar material, including mortar plastering which are often laid in, bound and pasted together by mortar; the term masonry can also refer to the building units themselves. The common materials of masonry construction are bricks and building stone such as marble, granite, and limestone, cast stone, concrete blocks, glass blocks, and adobe. Masonry is generally a highly durable form of construction. However, the materials used, the quality of the mortar and workmanship, and the pattern in which the units are assembled can substantially affect the durability of the overall masonry construction. A person who constructs masonry is called a mason or bricklayer. These are both classified as construction trades.

Stonemasonry or stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures, and sculpture using stone as the primary material. Stonemasonry is the craft of shaping and arranging stones, often together with mortar and even the ancient lime mortar, to wall or cover formed structures.

Mortar is a workable paste which hardens to bind building blocks such as stones, bricks, and concrete masonry units, to fill and seal the irregular gaps between them, spread the weight of them evenly, and sometimes to add decorative colors or patterns to masonry walls. In its broadest sense, mortar includes pitch, asphalt, and soft mud or clay, as those used between mud bricks, as well as cement mortar. The word "mortar" comes from Old French mortier, "builder's mortar, plaster; bowl for mixing." (13c.).

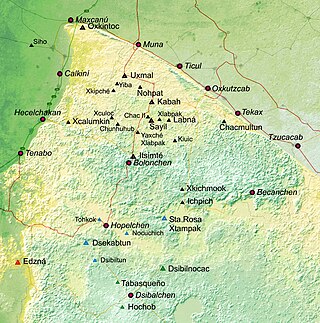

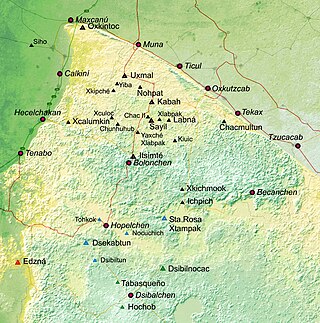

Puuc is the name of either a region in the Mexican state of Yucatán or a Maya architectural style prevalent in that region. The word puuc is derived from the Maya term for "hill". Since the Yucatán is relatively flat, this term was extended to encompass the large karstic range of hills in the southern portion of the state, hence, the terms Puuc region or Puuc hills. The Puuc hills extend into northern Campeche and western Quintana Roo.

The Pecos Classification is a chronological division of all known Ancestral Puebloans into periods based on changes in architecture, art, pottery, and cultural remains. The original classification dates back to consensus reached at a 1927 archæological conference held in Pecos, New Mexico, which was organized by the United States archaeologist Alfred V. Kidder.

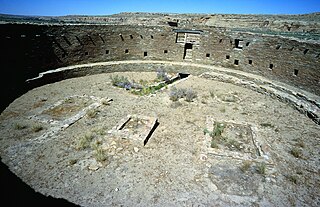

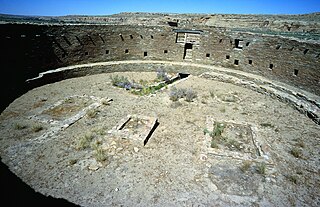

A kiva is a space used by Puebloans for rites and political meetings, many of them associated with the kachina belief system. Among the modern Hopi and most other Pueblo peoples, "kiva" means a large room that is circular and underground, and used for spiritual ceremonies.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park in the American Southwest hosting a concentration of pueblos. The park is located in northwestern New Mexico, between Albuquerque and Farmington, in a remote canyon cut by the Chaco Wash. Containing the most sweeping collection of ancient ruins north of Mexico, the park preserves one of the most important pre-Columbian cultural and historical areas in the United States.

A concrete block, also known as a cinder block in North American English, breeze block in British English, concrete masonry unit (CMU), or by various other terms, is a standard-size rectangular block used in building construction. The use of blockwork allows structures to be built in the traditional masonry style with layers of staggered blocks.

Ashlar is finely dressed stone, either an individual stone that has been worked until squared, or a structure built from such stones. Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, generally rectangular cuboid, mentioned by Vitruvius as opus isodomum, or less frequently trapezoidal. Precisely cut "on all faces adjacent to those of other stones", ashlar is capable of very thin joints between blocks, and the visible face of the stone may be quarry-faced or feature a variety of treatments: tooled, smoothly polished or rendered with another material for decorative effect.

Pueblo Bonito is the largest and best-known great house in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, northern New Mexico. It was built by the Ancestral Puebloans who occupied the structure between AD 828 and 1126.

Stone veneer is a thin layer of any stone used as decorative facing material that is not meant to be load bearing. Stone cladding is a stone veneer, or simulated stone, applied to a building or other structure made of a material other than stone. Stone cladding is sometimes applied to concrete and steel buildings as part of their original architectural design.

Chetro Ketl is an Ancestral Puebloan great house and archeological site located in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico, United States. Construction on Chetro Ketl began c. 990 and was largely complete by 1075, with significant remodeling occurring in the early and mid-1110s. Following the onset of a severe drought, most Chacoans emigrated from the canyon by 1140; by 1250 Chetro Ketl's last inhabitants had vacated the structure.

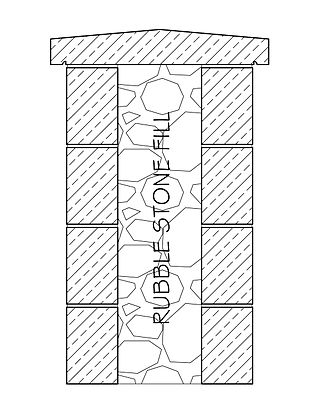

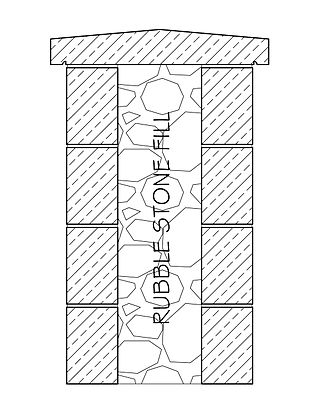

Rubble masonry or rubble stone is rough, uneven building stone not laid in regular courses. It may fill the core of a wall which is faced with unit masonry such as brick or ashlar. Some medieval cathedral walls have outer shells of ashlar with an inner backfill of mortarless rubble and dirt.

The history of construction embraces many other fields, including structural engineering, civil engineering, city growth and population growth, which are relatives to branches of technology, science, history, and architecture. The fields allow both modern and ancient construction to be analyzed, as well as the structures, building materials, and tools used.

Hundreds of Ancestral Puebloan dwellings are found across the American Southwest. With almost all constructed well before 1492 CE, these Puebloan towns and villages are located throughout the geography of the Southwest.

The Pueblo II Period was the second pueblo period of the Ancestral Puebloans of the Four Corners region of the American southwest. During this period people lived in dwellings made of stone and mortar, enjoyed communal activities in kivas, built towers and dams for water conservation, and implemented milling bins for processing maize. Communities with low-yield farms traded pottery with other settlements for maize.

Casa Rinconada is an Ancestral Puebloan archaeological site located atop a ridge adjacent to a small rincon across from Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, northwestern New Mexico, United States.

Casamero Pueblo is an archaeological site including the partially excavated and stabilized ruins of an 11th-century Ancestral Puebloan community in Prewitt, New Mexico in McKinley County. It was an outlier of Chaco Canyon. It is on the Trail of the Ancients Scenic Byway.

The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi, were an ancient Native American culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southwestern Colorado. They are believed to have developed, at least in part, from the Oshara tradition, which developed from the Picosa culture. The people and their archaeological culture are often referred to as Anasazi, meaning "ancient enemies", as they were called by Navajo. Contemporary Puebloans object to the use of this term, with some viewing it as derogatory.

McElmo Phase refers to a period in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, when drastic changes in ceramics and masonry techniques in Chaco Canyon appeared. During this period the Ancestral Puebloans living in the canyon started using painted black-on-white pottery versus their standard grey ware, and the masonry and layout of great houses built during the McElmo phase, which was the last major construction era in the canyon, differ significantly from those built during the early parts of the Bonito Phase, which overlaps with the McElmo Phase. Archeologists initially suggested that the McElmo influence was brought to Chaco Canyon by immigrants from Mesa Verde, but subsequent research suggests that the developments were of local origin. Archeologist R. Gwinn Vivian notes, "The jury is still out on this question, a problem that poses intriguing possibilities for future work."