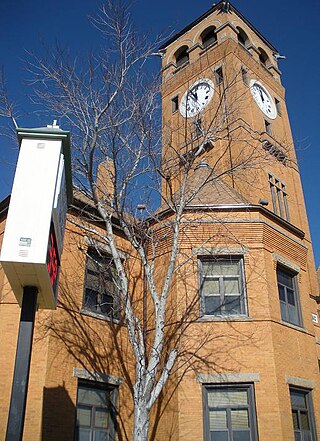

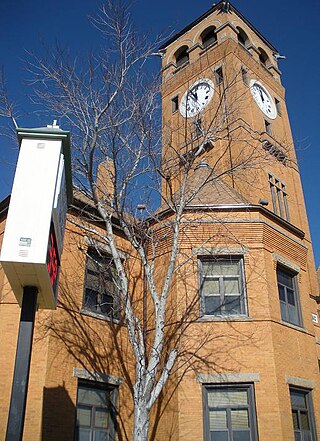

Tuskegee is a city in Macon County, Alabama, United States. General Thomas Simpson Woodward, a Creek War veteran under Andrew Jackson, laid out the city and founded it in 1833. It became the county seat in the same year and it was incorporated in 1843. It is the most populous city in Macon County. At the 2020 census the population was 9,395, down from 9,865 in 2010 and 11,846 in 2000.

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male was a study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the United States Public Health Service (PHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on a group of nearly 400 African American men with syphilis. The purpose of the study was to observe the effects of the disease when untreated, though by the end of the study medical advancements meant it was entirely treatable. The men were not informed of the nature of the experiment, and more than 100 died as a result.

Tuskegee University is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on July 4th in 1881 by Lewis Adams, and Booker T. Washington with help from the Alabama legislature via funding from two politicians seeking black votes.

Daniel Hale Williams was an American surgeon and hospital founder. An African American, he founded Provident Hospital in 1891, which was the first non-segregated hospital in the United States. Provident also had an associated nursing school for African Americans. He is known for having completed the first successful heart surgery.

Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson was an American physician and the first woman to be licensed as a physician in the U.S. state of Alabama.

Lewis Adams was an African-American former slave in Macon County, Alabama, who is best remembered for his work in helping found the school in 1881 in Tuskegee, Alabama which grew to become the normal school that with its first principal, Booker T Washington, grew to become Tuskegee University.

Fred David Gray is an American civil rights attorney, preacher, activist, and state legislator from Alabama. He handled many prominent civil rights cases, such as Browder v. Gayle, and was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives in 1970, along with Thomas Reed, both from Tuskegee. They were the first black state legislators in Alabama in the 20th century. He served as the president of the National Bar Association in 1985, and in 2001 was elected as the first African-American President of the Alabama State Bar.

The Tuskegee Veterans Administration Medical Center began in 1923 as an old soldiers' home in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was originally called the Tuskegee Home, part of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers system.

Maude E. Callen was a nurse-midwife in the South Carolina Lowcountry for over 60 years. Her work was brought to national attention in W. Eugene Smith's photo essay "Nurse Midwife," published in Life on December 3, 1951.

Samuel Leamon Younge Jr. was a civil rights and voting rights activist who was murdered for trying to desegregate a "whites only" restroom. Younge was an enlisted service member in the United States Navy, where he served for two years before being medically discharged. Younge was an active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and a leader of the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League.

William H. McAlpine was a Baptist minister and educator in Alabama. He was a founder and the second president of Selma University. He was a leader in the Baptist church and a founder and president of the Baptist Foreign Mission Convention. Later in his life he was Dean of the Theological Department at Selma.

Eugene Heriot Dibble Jr. (1893–1968) was an American physician and head of the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. He played an important role in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which was a clinical study conducted on syphilis in African American males from 1932 to 1972.

Dr. Winston Clifton Hackett (1881–1949) was the first African American physician in Arizona. He was the founder of the Booker T. Washington Memorial Hospital, which was the first hospital in Phoenix which served the African American community.

John Andrew Kenney Sr. was an African-American surgeon who was the medical director and chief surgeon of the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, from 1902 to 1922. He served as secretary of the National Medical Association (NMA) from 1904 to 1912, and was elected president of the NMA in 1912. He was the editor-in-chief of its journal, the Journal of the National Medical Association, from 1916 to 1948. He also served as the personal physician of both Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver.

Sherman Windham White Jr. †) was a U.S. Army Air Force officer and combat fighter pilot with the all-African American 332nd Fighter Group's 99th Fighter Squadron, best known as the Tuskegee Airmen.

Burgess E. Scruggs was an American physician, alderman, and civic leader in Huntsville, Alabama. He was one of Alabama's first African American doctors, and the first in Huntsville. He served four terms on Huntsville's city council.

Will or Willie Temple was an African American man who was lynched by a white mob on September 30, 1919, in Montgomery, Alabama.

Hale Infirmary was a hospital in Montgomery, Alabama, for African American citizens during a time of segregation. It was the first such hospital in the city; founded in 1890 by Dr. Cornelius Nathaniel Dorsette, it was in operation until 1958.

The Centennial Hill Historic District is a historic district in Montgomery, Alabama. The neighborhood sits to the southeast of downtown Montgomery, and is the city's most historic Black neighborhood. The district was listed on the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage in 1992 and the National Register of Historic Places in 2024.

Arthur McKinnon Brown, also known as Arthur McKimmon Brown, was an American physician. In the city of Birmingham, Alabama, Brown was one of the earliest African American physicians, and the first African American surgeon in the United States Army. He was an influential in the creation of the Children's Home Hospital of Birmingham. For many years it was the only hospital in the city where Black doctors could practice.