The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, or simply Zaporozhians were Cossacks who lived beyond the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossacks and Sloboda Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossacks played an important role in the history of Ukraine and the ethnogenesis of Ukrainians.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739 between Russia and the Ottoman Empire was caused by the Ottoman Empire's war with Persia and continuing raids by the Crimean Tatars. The war also represented Russia's ongoing struggle for access to the Black Sea. In 1737, the Habsburg monarchy joined the war on Russia's side, known in historiography as the Austro-Turkish War of 1737–1739.

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 - 1783, the longest-lived of the Turkic khanates that succeeded the empire of the Golden Horde. Established by Hacı I Giray in 1441, it was regarded as the direct heir to the Golden Horde and to Desht-i-Kipchak.

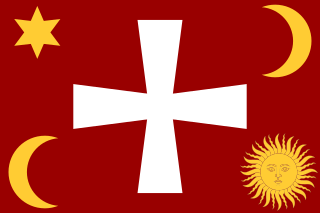

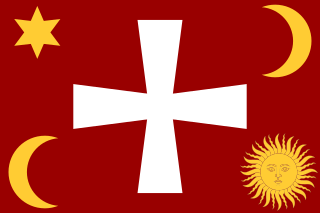

The Zaporozhian Sich was a semi-autonomous polity and proto-state of Cossacks that existed between the 16th to 18th centuries, including as an autonomous stratocratic state within the Cossack Hetmanate for over a hundred years, centred around the region now home to the Kakhovka Reservoir and spanning the lower Dnieper river in Ukraine. In different periods the area came under the sovereignty of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Ottoman Empire, the Tsardom of Russia, and the Russian Empire.

Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny was a political and civic leader, who was a Hetman of Ukrainian Cossacks from 1616 to 1622. As hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, he transformed the Zaporozhian Host from irregular military troops into a regular army. During his tenure, a greater common identity developed within the Cossacks, the Orthodox clergy and peasants of Ukraine, which would ultimately be inherited as a modern national consciousness. A military leader of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth both on land and sea, his troops played a significant role in the Battle of Khotyn against the Ottoman Empire in 1621 and the Polish Prince Władysław IV Vasa's attempt to gain the Tsardom of Russia in 1618.

Devlet I Giray ruled as Crimean Khan during a long and eventful period marked by significant historical events. These events included the fall of Kazan to Russia in 1552, the fall of the Astrakhan Khanate to Russia in 1556, and the burning of Moscow by the Crimean Tatars in 1571. Another notable event during Devlet's reign was the defeat of the Crimeans near Moscow in 1572. However, Cossack raids into the Crimea were also common during his reign.

Yurii Khmelnytsky, younger son of the famous Ukrainian Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky and brother of Tymofiy Khmelnytsky, was a Zaporozhian Cossack political and military leader. Although he spent half of his adult life as a monk and archimandrite, he also was Hetman of Ukraine on several occasions — in 1659-1660 and 1678–1681 and starost of Hadiach, becoming one of the most well-known Ukrainian politicians of the "Ruin" period for the Cossack Hetmanate.

The Russo-Crimean Wars were fought between the forces of the Tsardom of Russia and the Crimean Khanate during the 16th century over the region around the Volga River.

The Ottoman Navy or The Imperial Navy, also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos, the site of the first Ottoman naval shipyard and the nucleus of the future navy.

Khan Temir was a steppe warlord and raider. He ruled the Budjak Horde in what is now the southwestern corner of Ukraine (Budjak) along the Romanian border. Budjak is the southwesternmost corner of the Eurasian Steppe. He raided mostly along the eastern frontier of the Polish Commonwealth. Nominally a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, the Ottomans used him to pressure the Poles just as the Poles used the Zaporozhian Cossacks to pressure the Ottomans and Crimeans. His habit of acting independently caused problems. The Ottomans several times tried to move him east from Poland and eventually executed him. The most important event in his life was his conflict with the Crimean khan in 1628.

The Wild Fields is a historical term used in the Polish–Lithuanian documents of the 16th to 18th centuries to refer to the Pontic steppe in the territory of present-day Eastern and Southern Ukraine and Western Russia, north of the Black Sea and Azov Sea. It was the traditional name for the Black Sea steppes in the 16th and 17th centuries. In a narrow sense, it is the historical name for the demarcated and sparsely populated Black Sea steppes between the middle and lower reaches of the Dniester in the west, the lower reaches of the Don and the Siverskyi Donets in the east, from the left tributary of the Dnipro — Samara, and the upper reaches of the Southern Bug — Syniukha and Ingul in the north, to the Black and Azov Seas and Crimea in the south.

Damat Halil Pasha, also known as Halil Pasha, was an Ottoman Armenian statesman. He was grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire in 1616–1619 and 1626–1628. He also served in the Ottoman Navy, and led a number of attacks including the Raid of Żejtun in Malta in 1614.

Ğazı II Giray was a khan of the Crimean Khanate. Born in 1554, he distinguished himself in the Ottoman–Safavid War (1578–90), gaining the trust of his Ottoman suzerains. He was appointed khan in 1588, after his homeland experienced a period of political turmoil. He failed to capture Moscow during his 1591 campaign against Tsardom of Russia, however he managed to secure a favorable peace treaty two years later. He was then summoned to support his Ottoman allies in the Long Turkish War, taking part in multiple military expeditions centered in Hungary. In late 1596, the Ottoman sultan briefly unseated Ğazı II Giray in favor of Fetih I Giray after heeding the advice of Grand Vizier Cığalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha. He returned to power three months later, continuing his reign until his death in November 1607.

Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe were the slave raids, for over three centuries, conducted by the military of the Crimean Khanate and the Nogai Horde primarily in lands controlled by Russia and Poland-Lithuania as well as other territories, often under the sponsorship of the Ottoman Empire.

Mehmed III Giray was a khan of the Crimean Khanate. Much of his life was spent in conflict with nearly everyone around him. Part of the trouble was caused by his over-aggressive brother Shahin Giray. His reign was marked by an unsuccessful Turkish attempt to expel him and by the first treaty between Crimea and the Zaporozhian Cossacks. He was driven out by the Turks in 1628 and died trying to regain his throne.

The Cossack raid on Istanbul (Constantinople) of 1615 was an attack on Istanbul by the Zaporozhian Cossacks, led by Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny. Cossacks attacked the harbor of the city and burned it before returning to Ukraine. The success of this raid inspired the Tutora campaign of 1620 and the Khotyn campaign of 1621.

Islyam II Giray was a khan of the Crimean Khanate. His long stay in Turkey, theological training, and possibly age, may have unfitted him to rule. Most of the fighting was done by his brother Alp Giray. He was one of the many sons of Devlet I Giray. His reign was briefly interrupted by the usurpation of his nephew Saadet, and much of his reign was spent in conflict with Saadet and his brothers, the sons of his murdered brother and predecessor, Mehmed II Giray. Unlike many Crimean khans he died of natural causes.

Canibek or Janibek Giray was twice khan of the Crimean Khanate. During his first reign he fought for the Turks in Persia and Poland. He proved a poor commander and had difficulty making his men obey. He was removed by the Turks in 1623. In the following year the Turks tried to restore him and failed. During his second reign there were raids on Poland and Russia. The Turks again removed him and he died in exile.

Samiylo Kishka was a nobleman from Bratslav. He was a kish otaman and Hetman of Zaporozhian Sich. Samiylo Kishka headed the Cossack army in a range of sea campaigns against the Turks, Moldavian raids, the Livonian campaign (1600-1603), as well as a number of maritime campaigns against the Crimean Khanate: Gezlev, Izmail, Ochakiv, and Ackerman.

Lacy's campaign to Crimea was a military expedition from May to October 1737 by the Don army under the command of Field Marshal Peter Lacy, along with Cossacks and Kalmyk auxiliary cavalry led by Prince Galdan-Narbo, against the forces of the Crimean Khanate led by Fetih II Giray during the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739. The battles culminated in Russian victory at the Salgir River in Crimea on July 12, 1737, and in the vicinity of Karasubazar on July 14.