In psychology, a counterphobic attitude is a response to anxiety that, instead of fleeing the source of fear in the manner of a phobia, actively seeks it out, in the hope of overcoming the original anxiousness. [1]

Contrary to the avoidant personality disorder, the counterphobic represents the less usual, but not totally uncommon, response of seeking out what is feared. [2] Codependents may fall into a subcategory of this group, hiding their fears of attachment in over-dependency. [3]

Dare-devil activities are often undertaken in a counterphobic spirit, as a denial of the fears attached to them, which may be only partially successful. [4] Acting out in general may have a counterphobic source, [5] reflecting a false self over-concerned with compulsive doing to preserve a sense of power and control. [6]

Sex is a key area for counterphobic activity, sometimes powering hypersexuality in people who are actually afraid of the objects they believe they love. [7] Adolescents, fearing sex play, may jump over to a kind of spurious full sexuality; [8] adults may overvalue sex to cover an unconscious fear of the harm it may do. [9] Such a counterphobic approach may indeed be socially celebrated [10] in a postmodern vision of sex as gymnastic performance or hygiene, [11] fuelled by what Ken Wilber described as "an exuberant and fearless shallowness". [12]

Traffic accidents have been linked to a counterphobic, manic attitude in the driver. [13]

Julia Kristeva considered that language could be used by the developing child as a counterphobic object, [14] [ clarification needed ] protecting against anxiety and loss. [15]

Ego psychology points out that through the ambiguities of language, the concrete meanings of words may break down the counterphobic attitude and return the child to a state of fear. [16]

Didier Anzieu saw Freud's theorisation of psychoanalysis as a counterphobic defence against anxiety through intellectualisation: permanently ruminating on the instinctive, emotional world that was the actual object of fear. [17]

Wilhelm Fliess has been seen as playing the role of counterphobic object for Freud during the period of the latter's self-analysis. [18]

Otto Fenichel considered that undoing systematised counterphobic defences was only a first step in therapy, needing to be followed by analysis of the original anxiety itself. [19] He also considered that psychological trauma could break down counterphobic defences, with results that "may be very painful for the patient; they are, from a therapeutic point of view, favorable". [20]

David Rapaport emphasised the need for caution and extreme slowness in analyzing counterphobic defences. [21]

The attraction of horror movies has been seen to lie in a counterphobic impulse. [22]

Many actors often have a shy personality when off-camera, released counterphobically in conditions of performance. [23]

The Batman comics and movies often take Bruce Wayne's fear of bats as a central part of his origin story.

Sick , the documentary on performance artist Bob Flanagan, discusses the counterphobic attitude of Flanagan, who sought to escape the chronic pain of his cystic fibrosis by engaging in extreme acts of masochism.

Psychoanalysis is a theory developed by Sigmund Freud. It describes the human soul as an apparatus that emerged along the path of evolution and consists mainly of three parts that complement each other in a similar way to the organelles: a set of innate needs, a consciousness that serves to satisfy them, and a memory for the retrievable storage of experiences during made. Further in, it includes insights into the effects of traumatic education and a technique for bringing repressed content back into the realm of consciousness, in particular the diagnostic interpretation of dreams. Overall, psychoanalysis represents a method for the treatment of mental disorders.

Neurosis is a term mainly used today by followers of Freudian thinking to describe mental disorders caused by past anxiety, often that has been repressed. In recent history, the term has been used to refer to anxiety-related conditions more generally.

Psychoanalytic theory is the theory of personality organization and the dynamics of personality development relating to the practice of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology. First laid out by Sigmund Freud in the late 19th century, psychoanalytic theory has undergone many refinements since his work. The psychoanalytic theory came to full prominence in the last third of the twentieth century as part of the flow of critical discourse regarding psychological treatments after the 1960s, long after Freud's death in 1939. Freud had ceased his analysis of the brain and his physiological studies and shifted his focus to the study of the psyche, and on treatment using free association and the phenomena of transference. His study emphasized the recognition of childhood events that could influence the mental functioning of adults. His examination of the genetic and then the developmental aspects gave the psychoanalytic theory its characteristics.

The genital stage in psychoanalysis is the term used by Sigmund Freud to describe the final stage of human psychosexual development. The individual develops a strong sexual interest in people outside of the family.

In psychoanalysis, egosyntonic refers to the behaviors, values, and feelings that are in harmony with or acceptable to the needs and goals of the ego, or consistent with one's ideal self-image. Egodystonic is the opposite, referring to thoughts and behaviors that are conflicting or dissonant with the needs and goals of the ego, or further, in conflict with a person's ideal self-image.

Repression is a key concept of psychoanalysis, where it is understood as a defense mechanism that "ensures that what is unacceptable to the conscious mind, and would if recalled arouse anxiety, is prevented from entering into it." According to psychoanalytic theory, repression plays a major role in many mental illnesses, and in the psyche of the average person.

In psychology, intellectualization (intellectualisation) is a defense mechanism by which reasoning is used to block confrontation with an unconscious conflict and its associated emotional stress – where thinking is used to avoid feeling. It involves emotionally removing one's self from a stressful event. Intellectualization may accompany, but is different from, rationalization, the pseudo-rational justification of irrational acts.

Heinz Hartmann, was an Austrian psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. He is considered one of the founders and principal representatives of ego psychology.

Repetition compulsion is the unconscious tendency of a person to repeat a traumatic event or its circumstances. This may take the form of symbolically or literally re-enacting the event, or putting oneself in situations where the event is likely to occur again. Repetition compulsion can also take the form of dreams in which memories and feelings of what happened are repeated, and in cases of psychosis, may even be hallucinated.

Undoing is a defense mechanism in which a person tries to cancel out or remove an unhealthy, destructive or otherwise threatening thought or action by engaging in contrary behavior. For example, after thinking about being violent with someone, one would then be overly nice or accommodating to them. It is one of several defense mechanisms proposed by the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud during his career, many of which were later developed further by his daughter Anna Freud. The German term "Ungeschehenmachen" was first used to describe this defense mechanism. Transliterated, it means "making un-happened", which is essentially the core of "undoing". Undoing refers to the phenomenon whereby a person tries to alter the past in some way to avoid or feign disappearance of an adversity or mishap.

"Medusa's Head", by Sigmund Freud, is a very short, posthumously published essay on the subject of the Medusa Myth.

Don Juanism or Don Juan syndrome is a non-clinical term for the desire, in a man, to have sex with many different female partners. The name derives from the Don Juan of opera and fiction. The term satyriasis is sometimes used as a synonym for Don Juanism. The term has also been referred to as the male equivalent of nymphomania in women. These terms no longer apply with any accuracy as psychological or legal categories of psychological disorder.

Otto Fenichel was a psychoanalyst of the so-called "second generation". He was born into a prominent family of Jewish lawyers.

Splitting is the failure in a person's thinking to bring together the dichotomy of both perceived positive and negative qualities of something into a cohesive, realistic whole. It is a common defense mechanism wherein the individual tends to think in extremes. This kind of dichotomous interpretation is contrasted by an acknowledgement of certain nuances known as "shades of gray".

Identification is a psychological process whereby the individual assimilates an aspect, property, or attribute of the other and is transformed wholly or partially by the model that other provides. It is by means of a series of identifications that the personality is constituted and specified. The roots of the concept can be found in Freud's writings. The three most prominent concepts of identification as described by Freud are: primary identification, narcissistic (secondary) identification and partial (secondary) identification.

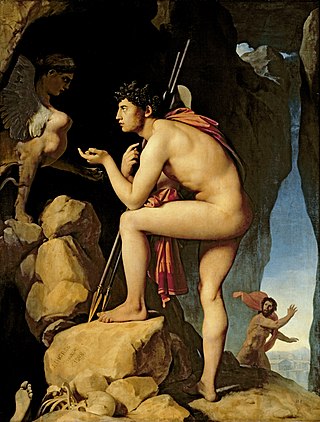

In classical psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus complex refers to a son's sexual attitude towards his mother and concomitant hostility toward his father, first formed during the phallic stage of psychosexual development. A daughter's attitude of desire for her father and hostility toward her mother is referred to as the feminine Oedipus complex. The general concept was considered by Sigmund Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), although the term itself was introduced in his paper A Special Type of Choice of Object made by Men (1910).

In psychology, narcissistic withdrawal is a stage in narcissism and a narcissistic defense characterized by "turning away from parental figures, and by the fantasy that essential needs can be satisfied by the individual alone". In adulthood, it is more likely to be an ego defense with repressed origins. Individuals feel obliged to withdraw from any relationship that threatens to be more than short-term, avoiding the risk of narcissistic injury, and will instead retreat into a comfort zone. The idea was first described by Melanie Klein in her psychoanalytic research on stages of narcissism in children.

Ernst Simmel was a German-American neurologist and psychoanalyst.

Paranoid anxiety is a term used in object relations theory, particularly in discussions about the Paranoid-schizoid and depressive positions. The term was frequently used by Melanie Klein, especially to refer to a pre-depressive and persecutory sense of anxiety characterised by the psychological splitting of objects.

Narcissistic neurosis is a term introduced by Sigmund Freud to distinguish the class of neuroses characterised by their lack of object relations and their fixation upon the early stage of libidinal narcissism. The term is less current in contemporary psychoanalysis, but still a focus for analytic controversy.