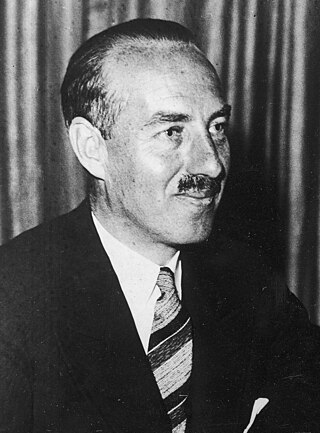

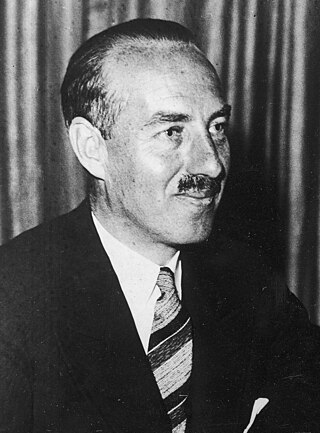

Paul Guillaume, Viscount van Zeeland was a Belgian lawyer, economist, Catholic politician and statesman.

The Rex Popular Front, Rexist Party, or simply Rex, was a far-right Catholic authoritarian and corporatist political party active in Belgium from 1935 until 1945. The party was founded by a journalist, Léon Degrelle. It advocated Belgian unitarism and royalism. Initially, the party ran in both Flanders and Wallonia, but it never achieved much success outside Wallonia and Brussels. Its name was derived from the Roman Catholic journal and publishing company Christus Rex.

Léon Joseph Marie Ignace Degrelle was a Belgian Walloon politician and Nazi collaborator. He rose to prominence in Belgium in the 1930s as the leader of the Rexist Party (Rex). During the German occupation of Belgium during World War II, he enlisted in the German army and fought in the Walloon Legion on the Eastern Front. After the collapse of the Nazi regime, Degrelle escaped and went into exile in Francoist Spain, where he remained a prominent figure in neo-Nazi politics.

Fort Breendonk is a former military installation at Breendonk, near Mechelen, Belgium, which served as a Nazi prison camp (Auffanglager) during the German occupation of Belgium during World War II.

The Walloon Legion was a unit of the German Army (Wehrmacht) and later of the Waffen-SS recruited among French-speaking collaborationists in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. It was formed in the aftermath of the German invasion of the Soviet Union and fought on the Eastern Front alongside similar formations from other parts of German-occupied Western Europe.

The Belgian Resistance collectively refers to the resistance movements opposed to the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. Within Belgium, resistance was fragmented between many separate organizations, divided by region and political stances. The resistance included both men and women from both Walloon and Flemish parts of the country. Aside from sabotage of military infrastructure in the country and assassinations of collaborators, these groups also published large numbers of underground newspapers, gathered intelligence and maintained various escape networks that helped Allied airmen trapped behind enemy lines escape from German-occupied Europe.

In World War II, many governments, organizations and individuals collaborated with the Axis powers, "out of conviction, desperation, or under coercion". Nationalists sometimes welcomed German or Italian troops they believed would liberate their countries from colonization. The Danish, Belgian and Vichy French governments attempted to appease and bargain with the invaders in hopes of mitigating harm to their citizens and economies.

Lucien Alphonse Joseph "José" Streel was a Belgian journalist and supporter of Rexism. Streel was an important figure in the early years of the movement, when he was the main political philosopher of Rexism as an ideology. He subsequently became less of a central figure following the German occupation of Belgium during World War II due to his lukewarm attitude towards working with Nazi Germany. Nevertheless, he was executed by Belgium after the war as a collaborator.

Paul Colin was a Belgian journalist, famous as the leading journalist and editor of the Rexist collaborationist newspapers "Le Nouveau Journal" and "Cassandre".

The Military Administration in Belgium and Northern France was an interim occupation authority established during the Second World War by Nazi Germany that included present-day Belgium and the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais. The administration was also responsible for governing the zone interdite, a narrow strip of territory running along the French northern and eastern borders. It remained in existence until July 1944. Plans to transfer Belgium from the military administration to a civilian administration were promoted by the SS, and Hitler had been ready to do so until Autumn 1942, when he put off the plans for what was intended to be temporary but ended up being permanent until the end of German occupation. The SS had suggested either Josef Terboven or Ernst Kaltenbrunner as the Reich Commissioner of the civilian administration.

Fredegardus Jacobus Josephus (Jef) van de Wiele was a Belgian Flemish Nazi politician. During the Nazi occupation of Belgium he became notorious as the leader of the most virulently pro-Nazi wing of Flemish politics.

Paul Hoornaert was a Belgian far right political activist. Although a pioneer of fascism in the country he was an opponent of German Nazism and, after joining the Belgian Resistance during the German occupation, died in Nazi custody.

Jean Denis was a Belgian politician and writer. Through his written work he was the chief ideologue of the Rexist movement.

Victor Matthys was a Belgian politician who served as both deputy and acting leader of the Rexist Party. He was later executed for collaboration with Nazi Germany.

Despite being neutral at the start of World War II, Belgium and its colonial possessions found themselves at war after the country was invaded by German forces on 10 May 1940. After 18 days of fighting in which Belgian forces were pushed back into a small pocket in the north-west of the country, the Belgian military surrendered to the Germans, beginning an occupation that would endure until 1944. The surrender of 28 May was ordered by King Leopold III without the consultation of his government and sparked a political crisis after the war. Despite the capitulation, many Belgians managed to escape to the United Kingdom where they formed a government and army-in-exile on the Allied side.

The National Royalist Movement was a group within the Belgian Resistance in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. It was active chiefly in Brussels and Flanders and was the most politically right-wing of the major Belgian resistance groups.

The German occupation of Belgium during World War II began on 28 May 1940, when the Belgian army surrendered to German forces, and lasted until Belgium's liberation by the Western Allies between September 1944 and February 1945. It was the second time in less than thirty years that Germany had occupied Belgium.

Events in the year 1944 in Belgium.

World War II in the Basque Country refers to the period extending from 1940 to 1945. It affected the French Basque Country, but also bordering areas across the Pyrenees on account of the instability following the end of the Spanish Civil War, and the friendly ties between Germany, Vichy France, and the triumphant Spanish military dictatorship.

The Abbeville massacre took place during the Battle of France in the French town of Abbeville on 20 May 1940. 21 political prisoners, mainly foreign nationals, were killed by the French soldiers who feared that they might become possible fifth columnists or collaborators with Nazi Germany.