The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone, however two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, these two parts are the neurocranium (braincase) and the viscerocranium that includes the mandible as its largest bone. The skull forms the anterior-most portion of the skeleton and is a product of cephalisation—housing the brain, and several sensory structures such as the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. In humans, these sensory structures are part of the facial skeleton.

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and values of societies. Linguistic anthropology studies how language affects social life, while economic anthropology studies human economic behavior. Biological (physical), forensic and medical anthropology study the biological development of humans, the application of biological anthropology in a legal setting and the study of diseases and their impacts on humans over time, respectively.

Forensic anthropology is the application of the anatomical science of anthropology and its various subfields, including forensic archaeology and forensic taphonomy, in a legal setting. A forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification of deceased individuals whose remains are decomposed, burned, mutilated or otherwise unrecognizable, as might happen in a plane crash. Forensic anthropologists are also instrumental in the investigation and documentation of genocide and mass graves. Along with forensic pathologists, forensic dentists, and homicide investigators, forensic anthropologists commonly testify in court as expert witnesses. Using physical markers present on a skeleton, a forensic anthropologist can potentially determine a person's age, sex, stature, and race. In addition to identifying physical characteristics of the individual, forensic anthropologists can use skeletal abnormalities to potentially determine cause of death, past trauma such as broken bones or medical procedures, as well as diseases such as bone cancer.

Osteology is the scientific study of bones, practised by osteologists. A subdiscipline of anatomy, anthropology, and paleontology, osteology is the detailed study of the structure of bones, skeletal elements, teeth, microbone morphology, function, disease, pathology, the process of ossification, and the resistance and hardness of bones (biophysics).

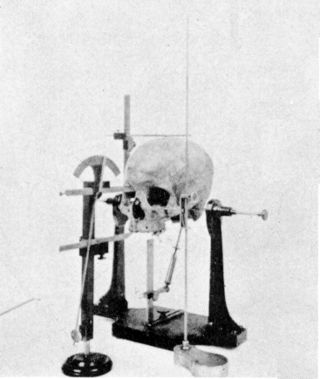

Craniometry is measurement of the cranium, usually the human cranium. It is a subset of cephalometry, measurement of the head, which in humans is a subset of anthropometry, measurement of the human body. It is distinct from phrenology, the pseudoscience that tried to link personality and character to head shape, and physiognomy, which tried the same for facial features. However, these fields have all claimed the ability to predict traits or intelligence.

The Badarian culture provides the earliest direct evidence of agriculture in Upper Egypt during the Predynastic Era. It flourished between 4400 and 4000 BC, and might have already emerged by 5000 BC.

The frontal suture is a fibrous joint that divides the two halves of the frontal bone of the skull in infants and children. Typically, it completely fuses between three and nine months of age, with the two halves of the frontal bone being fused together. It is also called the metopic suture, although this term may also refer specifically to a persistent frontal suture.

The Robert J. Terry Anatomical Skeletal Collection is a collection of some 1,728 human skeletons held by the Department of Anthropology of the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., United States. The skeletons have been widely used in research for anthropology and forensic science.

Forensic facial reconstruction is the process of recreating the face of an individual from their skeletal remains through an amalgamation of artistry, anthropology, osteology, and anatomy. It is easily the most subjective—as well as one of the most controversial—techniques in the field of forensic anthropology. Despite this controversy, facial reconstruction has proved successful frequently enough that research and methodological developments continue to be advanced.

William White Howells was a professor of anthropology at Harvard University.

In physical anthropology, post-orbital constriction is the narrowing of the cranium (skull) just behind the eye sockets found in most non-human primates and early hominins. This constriction is very noticeable in non-human primates, slightly less so in Australopithecines, even less in Homo erectus and completely disappears in modern Homo sapiens. Post-orbital constriction index in non-human primates and hominin range in category from increased constriction, intermediate, reduced constriction and disappearance. The post-orbital constriction index is defined by either a ratio of minimum frontal breadth (MFB), behind the supraorbital torus, divided by the maximum upper facial breadth (BFM), bifrontomalare temporale, or as the maximum width behind the orbit of the skull.

FORDISC is a software program created by Stephen Ousley and Richard Jantz. It is designed to help forensic anthropologists investigate the identity of a deceased person by providing estimates of the person's size, ethnicity, and biological sex based on the osteological material recovered.

Cephalometry is the study and measurement of the head, usually the human head, especially by medical imaging such as radiography. Craniometry, the measurement of the cranium (skull), is a large subset of cephalometry. Cephalometry also has a history in phrenology, which is the study of personality and character as well as physiognomy, which is the study of facial features. Cephalometry as applied in a comparative anatomy context informs biological anthropology. In clinical contexts such as dentistry and oral and maxillofacial surgery, cephalometric analysis helps in treatment and research; cephalometric landmarks guide surgeons in planning and operating.

Egypt has a long and involved demographic history. This is partly due to the territory's geographical location at the crossroads of several major cultural areas: North Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, Egypt has experienced several invasions and being part of many regional empires during its long history, including by the Canaanites, the Ancient Libyans, the Assyrians, the Kushites, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, and the Arabs.

Richard L. Jantz is an American anthropologist. He served as the director of the University of Tennessee Anthropological Research Facility from 1998–2011 and he is the current Professor Emeritus of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. His research focuses primarily on forensic anthropology, skeletal biology, dermatoglyphics, anthropometry, anthropological genetics, and human variation, as well as developing computerized databases in these areas which aid in anthropological research. The author of over a hundred journal articles and other publications, his research has helped lead and shape the field of physical and forensic anthropology for many years.

The Kow Swamp archaeological site comprises a series of late Pleistocene burials within the lunette of the eastern rim of a former lake known as Kow Swamp. The site is 10 kilometres (6 mi) south-east of Cohuna in the central Murray River valley, in northern Victoria, at 35.953553°S 144.318123°E. The site is significant for archaeological excavations by Alan Thorne between 1968 and 1972 which recovered the partial skeletal remains of more than 22 individuals.

The history of anthropometry includes its use as an early tool of anthropology, use for identification, use for the purposes of understanding human physical variation in paleoanthropology and in various attempts to correlate physical with racial and psychological traits. At various points in history, certain anthropometrics have been cited by advocates of discrimination and eugenics often as part of novel social movements or based upon pseudoscience.

Osteoware is a free data recording software for human skeletal material that is managed through the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. It is used by biological anthropologists to document data relevant to research and forensic applications of human skeletal remains in a standardized and consistent way. It has influenced other skeletal recording software, and has been successfully used at the Smithsonian for collecting data relevant to biological anthropology. Osteoware is the only free, individual-use software for the collection of data on skeletal material in anthropology.

The frontonasal suture is a cranial suture that is found in the human skull, connecting the frontal bone and the two nasal bones. This suture meets the internasal suture at the nasion. It is crucial in the study of cranial development and forensic analysis.

Mortuary archaeology is the study of human remains in their archaeological context. This is a known sub-field of bioarchaeology, which is a field that focuses on gathering important information based on the skeleton of an individual. Bioarchaeology stems from the practice of human osteology which is the anatomical study of skeletal remains. Mortuary archaeology, as well as the overarching field it resides in, aims to generate an understanding of disease, migration, health, nutrition, gender, status, and kinship among past populations. Ultimately, these topics help to produce a picture of the daily lives of past individuals. Mortuary archaeologists draw upon the humanities, as well as social and hard sciences to have a full understanding of the individual.