The Treaty of Nice was signed by European leaders on 26 February 2001 and came into force on 1 February 2003.

The law of Ireland consists of constitutional, statute, and common law. The highest law in the State is the Constitution of Ireland, from which all other law derives its authority. The Republic has a common-law legal system with a written constitution that provides for a parliamentary democracy based on the British parliamentary system, albeit with a popularly elected president, a separation of powers, a developed system of constitutional rights and judicial review of primary legislation.

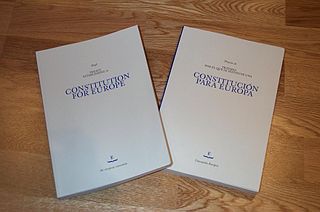

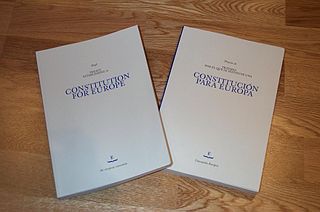

The Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe was an unratified international treaty intended to create a consolidated constitution for the European Union (EU). It would have replaced the existing European Union treaties with a single text, given legal force to the Charter of Fundamental Rights, and expanded qualified majority voting into policy areas which had previously been decided by unanimity among member states.

The Single European Act (SEA) was the first major revision of the 1957 Treaty of Rome. The Act set the European Community an objective of establishing a single market by 31 December 1992, and a forerunner of the European Union's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) it helped codify European Political Co-operation. The amending treaty was signed at Luxembourg City on 17 February 1986 and at The Hague on 28 February 1986. It came into effect on 1 July 1987, under the Delors Commission.

The Supreme Court of Ireland is the highest judicial authority in Ireland. It is a court of final appeal and exercises, in conjunction with the Court of Appeal and the High Court, judicial review over Acts of the Oireachtas. The Supreme Court also has appellate jurisdiction to ensure compliance with the Constitution of Ireland by governmental bodies and private citizens. It sits in the Four Courts in Dublin.

The Third Amendment of the Constitution Act 1972 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland that permitted the State to join the European Communities, which would later become the European Union, and provided that European Community law would take precedence over the constitution. It was approved by referendum on 10 May 1972, and signed into law by the President of Ireland Éamon de Valera on 8 June of the same year.

The Tenth Amendment of the Constitution Act 1987 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland that permitted the state to ratify the Single European Act. It was approved by referendum on 26 May 1987 and signed into law on 22 June of the same year.

The Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution Act 1992 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland permitted the state to ratify the Treaty on European Union, commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty. It was approved by referendum on 18 June 1992 and signed into law on 16 July of the same year.

The Eighteenth Amendment of the Constitution Act 1998 is an amendment of the Constitution of Ireland which permitted the state to ratify the Treaty of Amsterdam. It was approved by referendum on 22 May 1998 and signed into law on the 3 June of the same year. The referendum was held on the same day as the referendum on Nineteenth Amendment, which related to approval of the Good Friday Agreement.

The Twenty-third Amendment of the Constitution Act 2001 of the Constitution of Ireland is an amendment that permitted the state to become a party to the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was approved by referendum on 7 June 2001 and signed into law on the 27 March 2002. The referendum was held on the same day as referendums on the prohibition of the death penalty, which was also approved, and on the ratification of the Nice Treaty, which was rejected.

The Twenty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution Act 2002 is an amendment of the Constitution of Ireland which permitted the state to ratify the Treaty of Nice. It was approved by referendum on 19 October 2002 and signed into law on 7 November of the same year. The amendment followed a previous failed attempt to approve the Nice Treaty which was rejected in the first Nice referendum held in 2001.

Amendments to the Constitution of Ireland are only possible by way of referendum. A proposal to amend the Constitution of Ireland must first be approved by both Houses of the Oireachtas (parliament), then submitted to a referendum, and finally signed into law by the President of Ireland. Since the constitution entered into force on 29 December 1937, there have been 32 amendments to the constitution.

An entrenched clause or entrenchment clause of a constitution is a provision that makes certain amendments either more difficult or impossible to pass. Overriding an entrenched clause may require a supermajority, a referendum, or the consent of the minority party. The term eternity clause is used in a similar manner in the constitutions of Brazil, the Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, India, Iran, Italy, Morocco, Norway, and Turkey, but specifically applies to an entrenched clause that can never be overridden. However, if a constitution provides for a mechanism of its own abolition or replacement, like the German Basic Law does in Article 146, this by necessity provides a "back door" for getting rid of the "eternity clause", too.

The European Communities Act 1972 is an act of the Irish parliament, the Oireachtas, that incorporates the treaties and law of the European Union into the domestic law of Ireland. The Act did not just incorporate the law of the European Communities which existed at the time of its enactment, but incorporates legislative acts of the Community enacted subsequently. The Act also provides that government ministers may adopt statutory instruments (SIs) to implement EU law, and that those SIs are to have effect as if they were acts of parliament.

The Twenty-fourth Amendment of the Constitution Bill 2001 was a proposed amendment to the Constitution of Ireland to allow the state to ratify the Treaty of Nice of the European Union. The proposal was rejected in a referendum held in June 2001, sometimes referred to as the first Nice referendum. The referendum was held on the same day as referendums on the prohibition of the death penalty and on the ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, both of which were approved.

The primacy of European Union law is a legal principle establishing precedence of European Union law over conflicting national laws of EU member states.

The Twenty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution Act 2009 is an amendment of the Constitution of Ireland which permitted the state to ratify the Treaty of Lisbon of the European Union. It was approved by referendum on 2 October 2009.

On 21 June 2002, the Irish Government made a National Declaration at the Seville European Council emphasising its commitment to the European Union's security and defence policy.

The ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon was officially completed by all member states of the European Union on 13 November 2009 when the Czech Republic deposited its instrument of ratification with the Italian government. The Lisbon Treaty came into force on the first day of the month following the deposition of the last instrument of ratification with the government of Italy, which was 1 December 2009.

R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union is a United Kingdom constitutional law case decided by the United Kingdom Supreme Court on 24 January 2017, which ruled that the British Government might not initiate withdrawal from the European Union by formal notification to the Council of the European Union as prescribed by Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union without an Act of Parliament giving the government Parliament's permission to do so. Two days later, the government responded by bringing to Parliament the European Union Act 2017 for first reading in the House of Commons on 26 January 2017. The case is informally referred to as "the Miller case" or "Miller I".