Digital cinema refers to the adoption of digital technology within the film industry to distribute or project motion pictures as opposed to the historical use of reels of motion picture film, such as 35 mm film. Whereas film reels have to be shipped to movie theaters, a digital movie can be distributed to cinemas in a number of ways: over the Internet or dedicated satellite links, or by sending hard drives or optical discs such as Blu-ray discs.

35 mm film is a film gauge used in filmmaking, and the film standard. In motion pictures that record on film, 35 mm is the most commonly used gauge. The name of the gauge is not a direct measurement, and refers to the nominal width of the 35 mm format photographic film, which consists of strips 1.377 ± 0.001 inches (34.976 ± 0.025 mm) wide. The standard image exposure length on 35 mm for movies is four perforations per frame along both edges, which results in 16 frames per foot of film.

VistaVision is a higher resolution, widescreen variant of the 35 mm motion picture film format that was created by engineers at Paramount Pictures in 1954.

70 mm film is a wide high-resolution film gauge for motion picture photography, with a negative area nearly 3.5 times as large as the standard 35 mm motion picture film format. As used in cameras, the film is 65 mm (2.6 in) wide. For projection, the original 65 mm film is printed on 70 mm (2.8 in) film. The additional 5 mm contains the four magnetic stripes, holding six tracks of stereophonic sound. Although later 70 mm prints use digital sound encoding, the vast majority of existing and surviving 70 mm prints pre-date this technology.

16 mm film is a historically popular and economical gauge of film. 16 mm refers to the width of the film ; other common film gauges include 8 mm and 35 mm. It is generally used for non-theatrical film-making, or for low-budget motion pictures. It also existed as a popular amateur or home movie-making format for several decades, alongside 8 mm film and later Super 8 film. Eastman Kodak released the first 16 mm "outfit" in 1923, consisting of a camera, projector, tripod, screen and splicer, for US$335. RCA-Victor introduced a 16 mm sound movie projector in 1932, and developed an optical sound-on-film 16 mm camera, released in 1935.

Vitaphone was a sound film system used for feature films and nearly 1,000 short subjects made by Warner Bros. and its sister studio First National from 1926 to 1931. Vitaphone is the last major analog sound-on-disc system and the only one that was widely used and commercially successful. The soundtrack is not printed on the film, but issued separately on phonograph records. The discs, recorded at 33+1⁄3 rpm and typically 16 inches (41 cm) in diameter, are played on a turntable physically coupled to the projector motor while the film is projected. Its frequency response is 4300 Hz. Many early talkies, such as The Jazz Singer (1927), used the Vitaphone system. The name "Vitaphone" derived from the Latin and Greek words, respectively, for "living" and "sound".

A movie projector is an opto-mechanical device for displaying motion picture film by projecting it onto a screen. Most of the optical and mechanical elements, except for the illumination and sound devices, are present in movie cameras. Modern movie projectors are specially built video projectors.

A reel is a tool used to store elongated and flexible objects by wrapping the material around a cylindrical core known as a spool. Many reels also have flanges around the ends of the spool to help retain the wrapped material and prevent unwanted slippage off the ends. In most cases, the reel spool is hollow in order to pass an axle and allow it to spin like a wheel, a winding process known as reeling, which can be done by manually turning the reel with handles or cranks, or by machine-powered rotating via motors.

A film leader is a length of film attached to the head or tail of a film to assist in threading a projector or telecine. A leader attached to the beginning of a reel is sometimes known as a head leader, or simply head, and a leader attached to the end of a reel known as a tail leader or foot leader, or simply tail or foot.

Coded anti-piracy (CAP) is an anti-copyright infringement technology which marks each film print of a motion picture with a distinguishing pattern of dots, used as a forensic identifier to identify the source of illegal copies.

A projectionist is a person who operates a movie projector, particularly as an employee of a movie theater. Projectionists are also known as "operators".

In filmmaking, video production, animation, and related fields, a frame is one of the many still images which compose the complete moving picture. The term is derived from the historical development of film stock, in which the sequentially recorded single images look like a framed picture when examined individually.

The Academy ratio of 1.375:1 is an aspect ratio of a frame of 35 mm film when used with 4-perf pulldown. It was standardized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as the standard film aspect ratio in 1932, although similar-sized ratios were used as early as 1928.

28 mm film was introduced by the Pathé Film Company in 1912 under the name Pathé Kok. Geared toward the home market, 28 mm utilized diacetate film stock rather than the flammable nitrate commonly used in 35 mm. The film gauge was deliberately chosen such that it would be uneconomical to slit 35 mm nitrate film.

A release print is a copy of a film that is provided to a movie theater for exhibition.

Anamorphic format is the cinematography technique of shooting a widescreen picture on standard 35 mm film or other visual recording media with a non-widescreen native aspect ratio. It also refers to the projection format in which a distorted image is "stretched" by an anamorphic projection lens to recreate the original aspect ratio on the viewing screen. The word anamorphic and its derivatives stem from the Greek anamorphoo, compound of morphé with the prefix aná.

A projection booth, projection box or Bio box is a room or enclosure for the machinery required for the display of movies on a reflective screen, located high on the back wall of the presentation space. It is common in a movie theater.

A sound follower, also referred to as separate magnetic, sepmag, magnetic film recorder, or mag dubber, is a device for the recording and playback of film sound that is recorded on magnetic film. This device is locked or synchronized with the motion picture film containing the picture. It operates like an analog reel-to-reel audio tape recording, but using film, not magnetic tape. The unit can be switched from manual control to sync control, where it will follow the film with picture.

The DP70 is a model of motion picture projector, of which approximately 1,500 were manufactured by the Electro-Acoustics Division of Philips between 1954 and about 1968. It is notable for having been the first mass-produced theater projector in which 4/35 and 5/70 prints could be projected by a single machine, thereby enabling wide film to become a mainstream exhibition format, for its recognition in the 1963 Academy Awards, which led to it being described as "the only projector to win an Oscar", and for its longevity: a significant number remained in revenue-earning service as of February 2014.

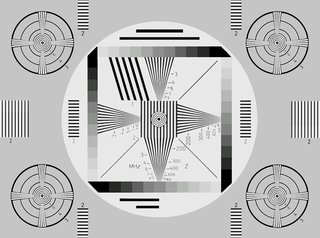

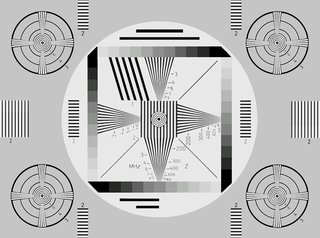

Test film are rolls or loops or slides of photographic film used for testing the quality of equipment. Equipment to be tested could include: telecine, motion picture film scanner, Movie projectors, Image scanners, film-out gear, Film recorders and Film scanners.