Related Research Articles

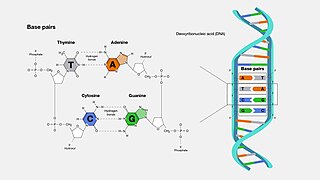

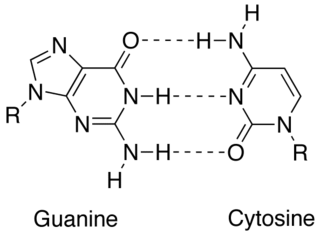

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA. Dictated by specific hydrogen bonding patterns, "Watson–Crick" base pairs allow the DNA helix to maintain a regular helical structure that is subtly dependent on its nucleotide sequence. The complementary nature of this based-paired structure provides a redundant copy of the genetic information encoded within each strand of DNA. The regular structure and data redundancy provided by the DNA double helix make DNA well suited to the storage of genetic information, while base-pairing between DNA and incoming nucleotides provides the mechanism through which DNA polymerase replicates DNA and RNA polymerase transcribes DNA into RNA. Many DNA-binding proteins can recognize specific base-pairing patterns that identify particular regulatory regions of genes.

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses. DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are nucleic acids. Alongside proteins, lipids and complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides), nucleic acids are one of the four major types of macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life.

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part of biological inheritance. This is essential for cell division during growth and repair of damaged tissues, while it also ensures that each of the new cells receives its own copy of the DNA. The cell possesses the distinctive property of division, which makes replication of DNA essential.

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create two identical DNA duplexes from a single original DNA duplex. During this process, DNA polymerase "reads" the existing DNA strands to create two new strands that match the existing ones. These enzymes catalyze the chemical reaction

Molecular genetics is a branch of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the structure and/or function of genes in an organism's genome using genetic screens.

DNA polymerase I is an enzyme that participates in the process of prokaryotic DNA replication. Discovered by Arthur Kornberg in 1956, it was the first known DNA polymerase. It was initially characterized in E. coli and is ubiquitous in prokaryotes. In E. coli and many other bacteria, the gene that encodes Pol I is known as polA. The E. coli Pol I enzyme is composed of 928 amino acids, and is an example of a processive enzyme — it can sequentially catalyze multiple polymerisation steps without releasing the single-stranded template. The physiological function of Pol I is mainly to support repair of damaged DNA, but it also contributes to connecting Okazaki fragments by deleting RNA primers and replacing the ribonucleotides with DNA.

Pyrosequencing is a method of DNA sequencing based on the "sequencing by synthesis" principle, in which the sequencing is performed by detecting the nucleotide incorporated by a DNA polymerase. Pyrosequencing relies on light detection based on a chain reaction when pyrophosphate is released. Hence, the name pyrosequencing.

A DNA construct is an artificially-designed segment of DNA borne on a vector that can be used to incorporate genetic material into a target tissue or cell. A DNA construct contains a DNA insert, called a transgene, delivered via a transformation vector which allows the insert sequence to be replicated and/or expressed in the target cell. This gene can be cloned from a naturally occurring gene, or synthetically constructed. The vector can be delivered using physical, chemical or viral methods. Typically, the vectors used in DNA constructs contain an origin of replication, a multiple cloning site, and a selectable marker. Certain vectors can carry additional regulatory elements based on the expression system involved.

In molecular biology, the term double helix refers to the structure formed by double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA. The double helical structure of a nucleic acid complex arises as a consequence of its secondary structure, and is a fundamental component in determining its tertiary structure. The structure was discovered by Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, her student Raymond Gosling, James Watson, and Francis Crick, while the term "double helix" entered popular culture with the 1968 publication of Watson's The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA.

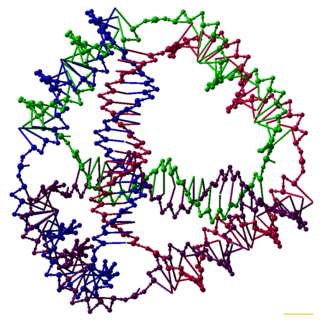

DNA origami is the nanoscale folding of DNA to create arbitrary two- and three-dimensional shapes at the nanoscale. The specificity of the interactions between complementary base pairs make DNA a useful construction material, through design of its base sequences. DNA is a well-understood material that is suitable for creating scaffolds that hold other molecules in place or to create structures all on its own.

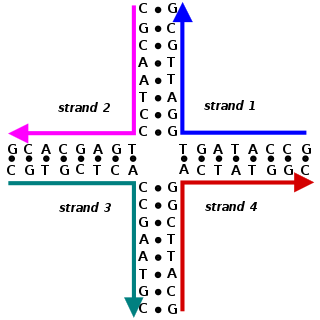

A Holliday junction is a branched nucleic acid structure that contains four double-stranded arms joined. These arms may adopt one of several conformations depending on buffer salt concentrations and the sequence of nucleobases closest to the junction. The structure is named after Robin Holliday, the molecular biologist who proposed its existence in 1964.

SNP genotyping is the measurement of genetic variations of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between members of a species. It is a form of genotyping, which is the measurement of more general genetic variation. SNPs are one of the most common types of genetic variation. An SNP is a single base pair mutation at a specific locus, usually consisting of two alleles. SNPs are found to be involved in the etiology of many human diseases and are becoming of particular interest in pharmacogenetics. Because SNPs are conserved during evolution, they have been proposed as markers for use in quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis and in association studies in place of microsatellites. The use of SNPs is being extended in the HapMap project, which aims to provide the minimal set of SNPs needed to genotype the human genome. SNPs can also provide a genetic fingerprint for use in identity testing. The increase of interest in SNPs has been reflected by the furious development of a diverse range of SNP genotyping methods.

Nucleic acid thermodynamics is the study of how temperature affects the nucleic acid structure of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). The melting temperature (Tm) is defined as the temperature at which half of the DNA strands are in the random coil or single-stranded (ssDNA) state. Tm depends on the length of the DNA molecule and its specific nucleotide sequence. DNA, when in a state where its two strands are dissociated, is referred to as having been denatured by the high temperature.

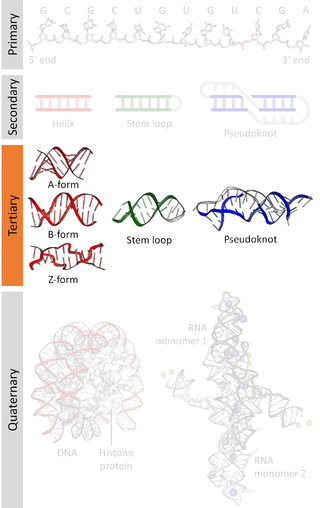

Nucleic acid tertiary structure is the three-dimensional shape of a nucleic acid polymer. RNA and DNA molecules are capable of diverse functions ranging from molecular recognition to catalysis. Such functions require a precise three-dimensional structure. While such structures are diverse and seemingly complex, they are composed of recurring, easily recognizable tertiary structural motifs that serve as molecular building blocks. Some of the most common motifs for RNA and DNA tertiary structure are described below, but this information is based on a limited number of solved structures. Many more tertiary structural motifs will be revealed as new RNA and DNA molecules are structurally characterized.

DNA nanotechnology is the design and manufacture of artificial nucleic acid structures for technological uses. In this field, nucleic acids are used as non-biological engineering materials for nanotechnology rather than as the carriers of genetic information in living cells. Researchers in the field have created static structures such as two- and three-dimensional crystal lattices, nanotubes, polyhedra, and arbitrary shapes, and functional devices such as molecular machines and DNA computers. The field is beginning to be used as a tool to solve basic science problems in structural biology and biophysics, including applications in X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of proteins to determine structures. Potential applications in molecular scale electronics and nanomedicine are also being investigated.

Nucleic acid secondary structure is the basepairing interactions within a single nucleic acid polymer or between two polymers. It can be represented as a list of bases which are paired in a nucleic acid molecule. The secondary structures of biological DNAs and RNAs tend to be different: biological DNA mostly exists as fully base paired double helices, while biological RNA is single stranded and often forms complex and intricate base-pairing interactions due to its increased ability to form hydrogen bonds stemming from the extra hydroxyl group in the ribose sugar.

In molecular biology, complementarity describes a relationship between two structures each following the lock-and-key principle. In nature complementarity is the base principle of DNA replication and transcription as it is a property shared between two DNA or RNA sequences, such that when they are aligned antiparallel to each other, the nucleotide bases at each position in the sequences will be complementary, much like looking in the mirror and seeing the reverse of things. This complementary base pairing allows cells to copy information from one generation to another and even find and repair damage to the information stored in the sequences.

Illumina dye sequencing is a technique used to determine the series of base pairs in DNA, also known as DNA sequencing. The reversible terminated chemistry concept was invented by Bruno Canard and Simon Sarfati at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. It was developed by Shankar Balasubramanian and David Klenerman of Cambridge University, who subsequently founded Solexa, a company later acquired by Illumina. This sequencing method is based on reversible dye-terminators that enable the identification of single nucleotides as they are washed over DNA strands. It can also be used for whole-genome and region sequencing, transcriptome analysis, metagenomics, small RNA discovery, methylation profiling, and genome-wide protein-nucleic acid interaction analysis.

Toehold mediated strand displacement (TMSD) is an enzyme-free molecular tool to exchange one strand of DNA or RNA (output) with another strand (input). It is based on the hybridization of two complementary strands of DNA or RNA via Watson-Crick base pairing (A-T/U and C-G) and makes use of a process called branch migration. Although branch migration has been known to the scientific community since the 1970s, TMSD has not been introduced to the field of DNA nanotechnology until 2000 when Yurke et al. was the first who took advantage of TMSD. He used the technique to open and close a set of DNA tweezers made of two DNA helices using an auxiliary strand of DNA as fuel. Since its first use, the technique has been modified for the construction of autonomous molecular motors, catalytic amplifiers, reprogrammable DNA nanostructures and molecular logic gates. It has also been used in conjunction with RNA for the production of kinetically-controlled ribosensors. TMSD starts with a double-stranded DNA complex composed of the original strand and the protector strand. The original strand has an overhanging region the so-called “toehold” which is complementary to a third strand of DNA referred to as the “invading strand”. The invading strand is a sequence of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) which is complementary to the original strand. The toehold regions initiate the process of TMSD by allowing the complementary invading strand to hybridize with the original strand, creating a DNA complex composed of three strands of DNA. This initial endothermic step is rate limiting and can be tuned by varying the strength (length and sequence composition e.g. G-C or A-T rich strands) of the toehold region. The ability to tune the rate of strand displacement over a range of 6 orders of magnitude generates the backbone of this technique and allows the kinetic control of DNA or RNA devices. After the binding of the invading strand and the original strand occurred, branch migration of the invading domain then allows the displacement of the initial hybridized strand (protector strand). The protector strand can possess its own unique toehold and can, therefore, turn into an invading strand itself, starting a strand-displacement cascade. The whole process is energetically favored and although a reverse reaction can occur its rate is up to 6 orders of magnitude slower. Additional control over the system of toehold mediated strand displacement can be introduced by toehold sequestering.

This glossary of cellular and molecular biology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts commonly used in the study of cell biology, molecular biology, and related disciplines, including genetics, biochemistry, and microbiology. It is split across two articles:

References

- ↑ Yurke B, Turberfield AJ, Mills AP, Simmel FC, Neumann JL (August 2000). "A DNA-fuelled molecular machine made of DNA". Nature. 406 (6796): 605–8. Bibcode:2000Natur.406..605Y. doi:10.1038/35020524. PMID 10949296. S2CID 2064216.