A stamp act is any legislation that requires a tax to be paid on the transfer of certain documents. Those who pay the tax receive an official stamp on their documents, making them legal documents. A variety of products have been covered by stamp acts including playing cards, dice, patent medicines, cheques, mortgages, contracts, marriage licenses and newspapers. The items often have to be physically stamped at approved government offices following payment of the duty, although methods involving annual payment of a fixed sum or purchase of adhesive stamps are more practical and common.

A revenue stamp, tax stamp, duty stamp or fiscal stamp is a (usually) adhesive label used to collect taxes or fees on documents, tobacco, alcoholic drinks, drugs and medicines, playing cards, hunting licenses, firearm registration, and many other things. Typically, businesses purchase the stamps from the government, and attach them to taxed items as part of putting the items on sale, or in the case of documents, as part of filling out the form.

Farming or tax-farming is a technique of financial management in which the management of a variable revenue stream is assigned by legal contract to a third party and the holder of the revenue stream receives fixed periodic rents from the contractor. It is most commonly used in public finance, where governments lease or assign the right to collect and retain the whole of the tax revenue to a private financier, who is charged with paying fixed sums into the treasury. Sometimes, as in the case of Miguel de Cervantes, the tax farmer was a government employee, paid a salary, and all money collected went to the government.

Stamp duty in the United Kingdom is a form of tax charged on legal instruments, and historically required a physical stamp to be attached to or impressed upon the document in question. The more modern versions of the tax no longer require a physical stamp.

A tamga or tamgha is an abstract seal or stamp used by Eurasian nomads and by cultures influenced by them. The tamga was normally the emblem of a particular tribe, clan or family. They were common among the Eurasian nomads throughout Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Income taxes are the most significant form of taxation in Australia, and collected by the federal government through the Australian Taxation Office. Australian GST revenue is collected by the Federal government, and then paid to the states under a distribution formula determined by the Commonwealth Grants Commission.

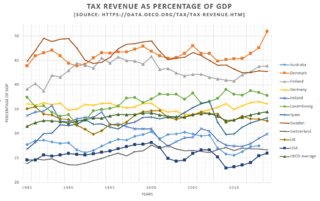

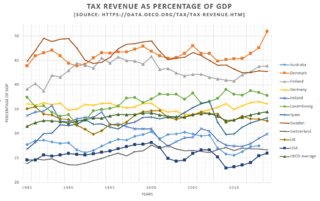

Taxation in Norway is levied by the central government, the county municipality and the municipality. In 2012 the total tax revenue was 42.2% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Many direct and indirect taxes exist. The most important taxes – in terms of revenue – are VAT, income tax in the petroleum sector, employers' social security contributions and tax on "ordinary income" for persons. Most direct taxes are collected by the Norwegian Tax Administration and most indirect taxes are collected by the Norwegian Customs and Excise Authorities.

The adet-i ağnam was an annual tax on sheep and goats in the Ottoman Empire. Initially, the tax was known as resm-i ağnam; the name changed around 1550.

Taxation in the Ottoman Empire changed drastically over time, and was a complex patchwork of different taxes, exemptions, and local customs.

The Resm-i Çift was a tax in the Ottoman Empire. It was a tax on farmland, assessed at a fixed annual rate per çift, and paid by land-owning Muslims. Some Imams and some civil servants were exempted from the resm-i çift.

The tuz resmi was a tax on salt in the Ottoman Empire.

The resm-i arus, or resm-i arusane, was a feudal bride-tax in the Ottoman Empire. It was typically a fixed fee, a divani tax; it was paid around the time of marriage, to the timar-holder, or even to a tax-farmer in their stead. The tax-collector might record details of individual marriages, although this was not equivalent to the church marriage-registers in contemporary western Europe and some of the tax records are unclear.

The gümrük resmi was a customs charge, or tax, in the Ottoman Empire. In modern-day Turkey the term continues to be in use: Gümrük vergi ve resimleri.

Sürsat was a form of food requisitioning with price controls, used by the Ottoman Empire to provide consumables for its armed forces. It was related to nüzül; sürsat was initially an obligation for the public to provide food and other supplies at a pre-fixed price which was unlikely to be favourable, or might even be merely symbolic. Istira was basically the same obligation, but supposedly at market price. Over time, nüzül, sürsat, and istira were all transformed into extraordinary cash taxes on people living near the route travelled by the army.

Müskirat resmi was a tax on alcohol in the Ottoman Empire.

The resm-i mücerred was a bachelor tax in the Ottoman Empire, related to the resm-i çift and the resm-i bennâk.

The tapu resmi was a feudal land tax in the Ottoman Empire.

Ihtisab, or ihtisap was a type of tax on markets in the Ottoman Empire; the muhtasib or ihtisap ağasi - the ihtisab collector - had a broader role in regulating and taxing markets under the authority of the kadı.

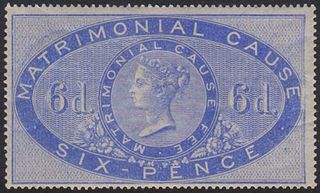

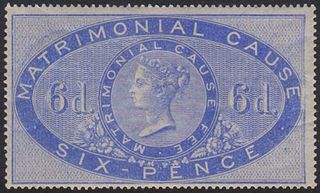

Revenue stamps of the United Kingdom refer to the various revenue or fiscal stamps, whether adhesive, directly embossed or otherwise, which were issued by and used in the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of Great Britain, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, from the late 17th century to the present day.