The obol was a form of ancient Greek currency and weight.

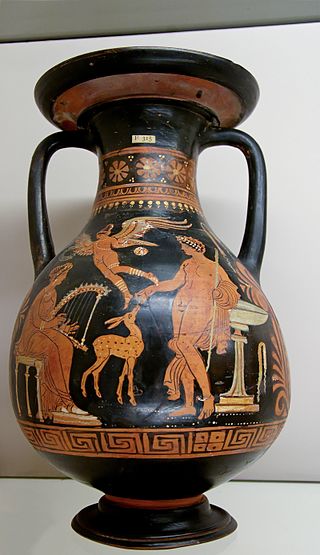

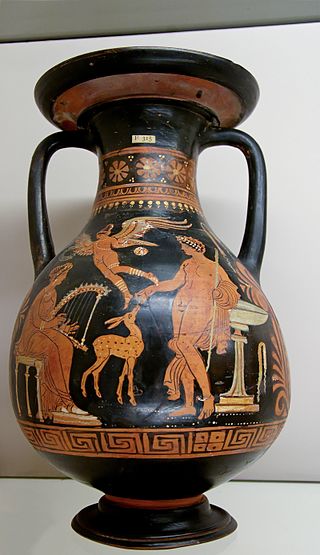

Red-figure pottery is a style of ancient Greek pottery in which the background of the pottery is painted black while the figures and details are left in the natural red or orange color of the clay.

Arthur Dale Trendall, was a New Zealand art historian and classical archaeologist whose work on identifying the work of individual artists on Greek ceramic vessels at Apulia and other sites earned him international prizes and a papal knighthood.

The Shuvalov Painter was an Attic vase painter of the red-figure style, active between 440 and 410 BC, i.e. in the High Classical period in Magna Graecia.

The Sisyphus Painter was an Apulian red-figure vase painter. His works are dated to the last two decades of the fifth century and the very early fourth century BC.

The Ilioupersis Painter was an Apulian vase painter. His works are dated to the second quarter of the 4th century BC.

The Darius Painter was an Apulian vase painter and the most eminent representative at the end of the "Ornate Style" in South Italian red-figure vase painting in Magna Graecia. His works were produced between 340 and 320 BC.

The Baltimore Painter was an Apulian vase painter whose works date to the final quarter of the 4th century BC. He is considered the most important Late Apulian vase painter, and the last Apulian painter of importance. His conventional name is derived from a vase kept at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

The Tarporley Painter was a Greek Apulian red-figure vase painter. His works date to the first quarter of the 4th century BC. The Tarporley Painter is his period's most important representative of the so-called "Plain Style". He is considered to have been the pupil and successor of the Sisyphus Painter, as indicated by his elegant fine-limbed figures and the solemn facial expressions of his woman and cloaked youths. He painted garments in a less balanced style then the Sisyphus Painter. His heads are often oval and lean forwards. The spaces between his figures are often filled with flowers, branches or vines. Over time, his drawing style becomes more fluid, but also less precise. He painted especially on bell kraters, on which he often depicted dionysiac themes and theatrical scenes. His work includes the first known phlyax vase, showing the punishment of a thief, accompanied by a metric verse inscription. Mythological scenes by him are rare. There appears to be an especially close relationship between the work of the Tarporley Painter and that of the Dolon Painter, perhaps they cooperated directly for some time. His succession is represented by three separate schools, each clearly influenced by him. The most important painter of the first is the Schiller Painter, of the second the Hoppin Painter and of the third the Painter of Karlsruhe B9 and the Dijon Painter.

The Varrese Painter was an Apulian red-figure vase painter. His works are dated to the middle of the 4th century BC.

Apulian vase painting was a regional style of South Italian vase painting from ancient Apulia in southeast Italy. It comprises geometric pottery and red-figure pottery.

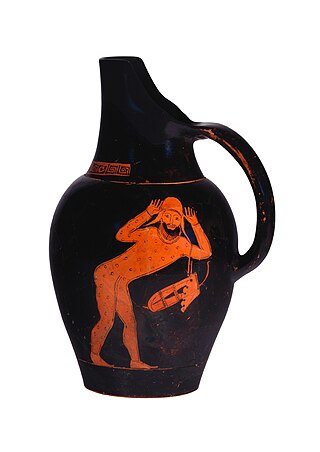

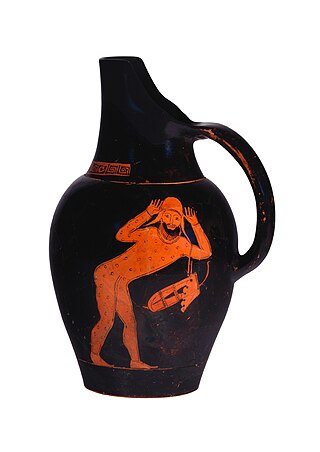

The Eurymedon vase is an Attic red-figure oinochoe, a wine jug attributed to the circle of the Triptolemos Painter made ca. 460 BC, which is now in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (1981.173) in Hamburg, Germany. It depicts two figures; a bearded man, naked except for a mantle, holding his erection in his right hand and reaching forward with his left, while the second figure in the traditional dress of an Oriental archer bends forward at the hips and twists his upper body to face the viewer while holding his hands open-palmed up before him, level with his head. Between these figures is an inscription that reads εύρυμέδον ειμ[í] κυβα[---] έστεκα, restored by Schauenburg as "I am Eurymedon, I stand bent forward". This vase is a frequently-cited source suggestive of popular Greek attitudes during the Classical period to same-sex relations, gender roles, and Greco-Persian relations.

The danake or danace was a small silver coin of the Persian Empire, equivalent to the Greek obol and circulated among the eastern Greeks. Later it was used by the Greeks in other metals. The 2nd-century AD grammarian Julius Pollux gives the name as danikê or danakê or danikon and says that it was a Persian coin, but by Pollux's time this was an anachronism.

The Arkesilas Painter was a Laconian vase painter active around 560 BC. He is considered one of the five great vase painters of Sparta.

Campanian vase painting is one of the five regional styles of South Italian red-figure vase painting fabricated in Magna Graecia. It forms a close stylistic community with Apulian vase painting.

Lucanian vase painting was substyle of South Italian red-figure vase painting fabricated in Magna Graecia, produced in Lucania between 450 and 325 BC. It was the oldest South Italian regional style. Together with Sicilian and Paestan vase painting, it formed a close stylistic community.

Paestan vase painting was a style of vase painting associated with Paestum, a Campanian city in Italy founded by Greek colonists of Magna Graecia. Paestan vase painting is one of five regional styles of South Italian red-figure vase painting.

The Underworld Painter was an ancient Greek Apulian vase painter whose works date to the second half of the 4th century BC.

The Painter of the Berlin Dancing Girl was an Apulian red-figure vase painter, who was active between 430–410 BC. He was named after a calyx krater in the collection of the Antikensammlung Berlin, which depicts a girl dancing to the aulos played by a seated woman.

The find complex associated with a group of ancient Apulian picture vases for a funeral ceremony consists of 29 vases, plates, vase fragments, and fragment groups, which are showpieces of the Berlin Collection of Classical Antiquities in the Altes Museum. The vase ensemble comprises vases of varying sizes and values, consistently decorated with images in the rich style of Apulian vase painting. Additionally, there are vases of medium and low quality. All the pieces likely originate from a looted excavation in the latter half of the 20th century.