Related Research Articles

In music theory, the term mode or modus is used in a number of distinct senses, depending on context.

Medieval music encompasses the sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the first and longest major era of Western classical music and followed by the Renaissance music; the two eras comprise what musicologists generally term as early music, preceding the common practice period. Following the traditional division of the Middle Ages, medieval music can be divided into Early (500–1150), High (1000–1300), and Late (1300–1400) medieval music.

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. The Oxford Companion to Music describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation ; the second is learning scholars' views on music from antiquity to the present; the third is a sub-topic of musicology that "seeks to define processes and general principles in music". The musicological approach to theory differs from music analysis "in that it takes as its starting-point not the individual work or performance but the fundamental materials from which it is built."

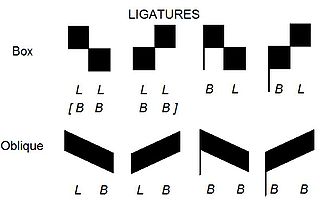

In music notation, a ligature is a graphic symbol that tells a musician to perform two or more notes in a single gesture, and on a single syllable. It was primarily used from around 800 to 1650 AD. Ligatures are characteristic of neumatic (chant) and mensural notation. The notation and meaning of ligatures has changed significantly throughout Western music history, and their precise interpretation is a continuing subject of debate among musicologists.

Pérotin was a composer associated with the Notre Dame school of polyphony in Paris and the broader ars antiqua musical style of high medieval music. He is credited with developing the polyphonic practices of his predecessor, Léonin, with the introduction of three and four-part harmonies.

Organum is, in general, a plainchant melody with at least one added voice to enhance the harmony, developed in the Middle Ages. Depending on the mode and form of the chant, a supporting bass line may be sung on the same text, the melody may be followed in parallel motion, or a combination of both of these techniques may be employed. As no real independent second voice exists, this is a form of heterophony. In its earliest stages, organum involved two musical voices: a Gregorian chant melody, and the same melody transposed by a consonant interval, usually a perfect fifth or fourth. In these cases the composition often began and ended on a unison, the added voice keeping to the initial tone until the first part has reached a fifth or fourth, from where both voices proceeded in parallel harmony, with the reverse process at the end. Organum was originally improvised; while one singer performed a notated melody, another singer—singing "by ear"—provided the unnotated second melody. Over time, composers began to write added parts that were not just simple transpositions, thus creating true polyphony.

Ars antiqua, also called ars veterum or ars vetus, is a term used by modern scholars to refer to the Medieval music of Europe during the High Middle Ages, between approximately 1170 and 1310. This covers the period of the Notre-Dame school of polyphony, and the subsequent years which saw the early development of the motet, a highly varied choral musical composition. Usually the term ars antiqua is restricted to sacred (church) or polyphonic music, excluding the secular (non-religious) monophonic songs of the troubadours, and trouvères. However, sometimes the term ars antiqua is used more loosely to mean all European music of the thirteenth century, and from slightly before. The term ars antiqua is used in opposition to ars nova, which refers to the period of musical activity between approximately 1310 and 1375.

Ars subtilior is a musical style characterized by rhythmic and notational complexity, centered on Paris, Avignon in southern France, and also in northern Spain at the end of the fourteenth century. The style also is found in the French Cypriot repertory. Often the term is used in contrast with ars nova, which applies to the musical style of the preceding period from about 1310 to about 1370; though some scholars prefer to consider ars subtilior a subcategory of the earlier style. Primary sources for ars subtilior are the Chantilly Codex, the Modena Codex, and the Turin Manuscript.

Anonymous IV is the designation given to the writer of an important treatise of medieval music theory. He was probably an English student working at Notre Dame de Paris, most likely in the 1270s or 1280s. Nothing is known about his life, not even his name. His writings survive in two partial copies from Bury St Edmunds; one from the 13th century, and one from the 14th.

Musica ficta was a term used in European music theory from the late 12th century to about 1600 to describe pitches, whether notated or added at the time of performance, that lie outside the system of musica recta or musica vera as defined by the hexachord system of Guido of Arezzo.

Franco of Cologne was a German music theorist and possibly a composer. He was one of the most influential theorists of the Late Middle Ages, and was the first to propose an idea which was to transform musical notation permanently: that the duration of any note should be determined by its appearance on the page, and not from context alone. The result was Franconian notation, described most famously in his Ars cantus mensurabilis.

Johannes de Garlandia was a French music theorist of the late ars antiqua period of medieval music. He is known for his work on the first treatise to explore the practice of musical notation of rhythm, De Mensurabili Musica.

In medieval music, the rhythmic modes were set patterns of long and short durations. The value of each note is not determined by the form of the written note, but rather by its position within a group of notes written as a single figure called a "ligature", and by the position of the ligature relative to other ligatures. Modal notation was developed by the composers of the Notre Dame school from 1170 to 1250, replacing the even and unmeasured rhythm of early polyphony and plainchant with patterns based on the metric feet of classical poetry, and was the first step towards the development of modern mensural notation. The rhythmic modes of Notre Dame Polyphony were the first coherent system of rhythmic notation developed in Western music since antiquity.

Marchetto da Padova was an Italian music theorist and composer of the late medieval era. His innovations in notation of time-values were fundamental to the music of the Italian ars nova, as was his work on defining the modes and refining tuning. In addition, he was the first music theorist to discuss chromaticism.

Hucbald was a Benedictine monk active as a music theorist, poet, composer, teacher, and hagiographer. He was long associated with the Saint-Amand Abbey, so is often known as Hucbald of St Amand. Deeply influenced by Boethius' De Institutione Musica, Hucbald's (De) Musica, formerly known as De harmonica institutione, aims at reconciling through many notated examples ancient Greek music theory and the contemporary practice of Gregorian chant. Among the leading music theorists of the Carolingian era, he was likely a near contemporary of fellow theorist Aurelian of Réôme, the unknown author of the Musica enchiriadis, as well as the anonymous authors of other music theory texts Commemeratio brevis, Alia musica and De modis.

Johannes de Grocheio was a Parisian musical theorist of the early 14th century. His French name was Jean de Grouchy, but he is best known by his Latinized name. He was the author of the treatise Ars musicae, which describes the functions of sacred and secular music in and around Paris during his lifetime.

Ars cantus mensurabilis is a music theory treatise from the mid-13th century, c. 1250–1280 written by German music theorist Franco of Cologne. The treatise was written shortly after De Mensurabili Musica, a treatise by Johannes de Garlandia, which summarised a set of six rhythmic modes in use at the time. In music written in rhythmic modes, the duration of a note could be determined only in context. Ars cantus mensurabilis was the first treatise to suggest that individual notes could have their own durations independent of context. This new rhythmic system was the foundation for the mensural notation system and the ars nova style.

The Berkeley Treatise is an anonymous 14th-century compilation of musicological writings. The treatise is in five sections: concerning fundamentals and mode, discant, mensuration, musica speculativa and tuning. The third section on mensuration is a version of the Libellus cantus mensurabilis by Johannes de Muris, dated to 1375.

Gilbert Reaney was an English musicologist who specialized in medieval and Renaissance music, theory and literature. Described as "one of the most prolific and influential musicologists of the past century", Reaney made significant contributions to his fields of expertise, particularly on the life and works of Guillaume de Machaut, as well as medieval music theory.

The American Institute of Musicology (AIM) is a musicological organization that researches, promotes and produces publications on early music. Founded in 1944 by Armen Carapetyan, the AIM's chief objective is the publication of modern editions of medieval, Renaissance and early Baroque compositions and works of music theory. Among the series it produces are the Corpus mensurabilis musicae (CMM), Corpus Scriptorum de Musica (CSM) and Corpus of Early Keyboard Music (CEKM). In CMM specifically, the AIM has published the entire surviving oeuvres of a considerable amount of composers, most notably the complete works of Guillaume de Machaut and Guillaume Du Fay, among many others. The CSM, which focuses on music theory, has published the treatises of important theorists such as Guido of Arezzo and Jean Philippe Rameau. The breadth and quality of publications produced by the AIM constitutes a central contribution to the study, practice and performance of early music.

References

- ↑ Christensen, Thomas. The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 628

- ↑ Taruskin, Richard. The Oxford History of western Music - I (Music from the earliest notations to the 16th Century) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010) p196/7

- ↑ There has been recent scholarly debate on whether Johannes de Garlandia actually wrote the treatise. Some music historians believe that he was simply editor of the treatises. More information can be found on his Wikipedia page.