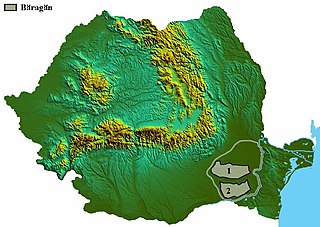

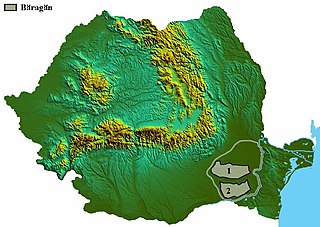

Transylvania is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains and to the west the Apuseni Mountains. Broader definitions of Transylvania also include the western and northwestern Romanian regions of Crișana and Maramureș, and occasionally Banat. Historical Transylvania also includes small parts of neighbouring Western Moldavia and even a small part of south-western neighbouring Bukovina to its north east.

During the later stages of World War II and the post-war period, Germans and Volksdeutsche fled and were expelled from various Eastern and Central European countries, including Czechoslovakia, and from the former German provinces of Lower and Upper Silesia, East Prussia, and the eastern parts of Brandenburg (Neumark) and Pomerania (Hinterpommern), which were annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union.

The Kingdom of Romania, under the rule of King Carol II, was initially a neutral country in World War II. However, Fascist political forces, especially the Iron Guard, rose in popularity and power, urging an alliance with Nazi Germany and its allies. As the military fortunes of Romania's two main guarantors of territorial integrity—France and Britain—crumbled in the Fall of France, the government of Romania turned to Germany in hopes of a similar guarantee, unaware that Germany, in the supplementary protocol to the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, had already granted its blessing to Soviet claims on Romanian territory.

Mass evacuation, forced displacement, expulsion, and deportation of millions of people took place across most countries involved in World War II. The Second World War caused the movement of the largest number of people in the shortest period of time in history. A number of these phenomena were categorised as violations of fundamental human values and norms by the Nuremberg Tribunal after the war ended. The mass movement of people – most of them refugees – had either been caused by the hostilities, or enforced by the former Axis and the Allied powers based on ideologies of race and ethnicity, culminating in the postwar border changes enacted by international settlements. The refugee crisis created across formerly occupied territories in World War II provided the context for much of the new international refugee and global human rights architecture existing today.

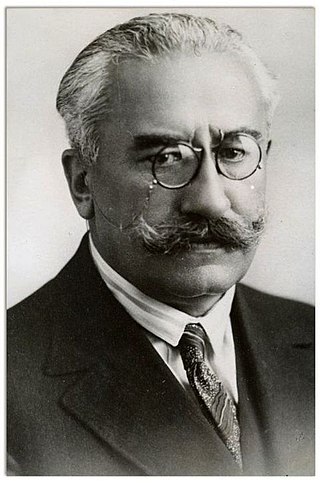

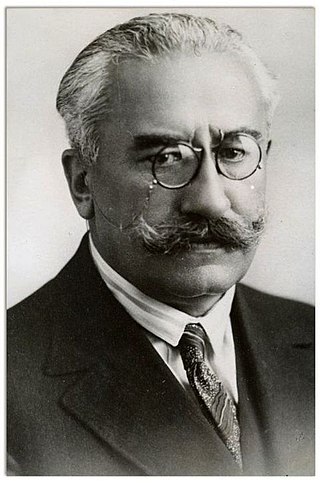

Nicolae Rădescu was a Romanian army officer and political figure. He was the last pre-communist rule Prime Minister of Romania, serving from 7 December 1944 to 1 March 1945.

The Transylvanian Saxons are a people of mainly German ethnicity and overall Germanic origin —mostly Luxembourgish and from the Low Countries initially during the medieval Ostsiedlung process, then also from other parts of present-day Germany— who settled in Transylvania in various waves, starting from the mid and mid-late 12th century until the mid 19th century.

Alexandru Vaida-Voevod or Vaida-Voievod was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian politician who was a supporter and promoter of the union of Transylvania with the Romanian Old Kingdom. He later served as 28th Prime Minister of Romania.

Northern Transylvania was the region of the Kingdom of Romania that during World War II, as a consequence of the August 1940 territorial agreement known as the Second Vienna Award, became part of the Kingdom of Hungary. With an area of 43,104 km2 (16,643 sq mi), the population was largely composed of both ethnic Romanians and Hungarians.

The Danube Swabians is a collective term for the ethnic German-speaking population who lived in the Kingdom of Hungary in east-central Europe, especially in the Danube River valley, first in the 12th century, and in greater numbers in the 17th and 18th centuries. Most were descended from earlier 18th-century Swabian settlers from Upper Swabia, the Swabian Jura, northern Lake Constance, the upper Danube, the Swabian-Franconian Forest, the Southern Black Forest and the Principality of Fürstenberg, followed by Hessians, Bavarians, Franconians and Lorrainers recruited by Austria to repopulate the area and restore agriculture after the expulsion of the Ottoman Empire. They were able to keep their language and religion and initially developed strongly German communities in the region with German folklore.

About 9.3% of Romania's population is represented by minorities, and 13% unknown or undisclosed according to 2021 census. The principal minorities in Romania are Hungarians and Romani people, with a declining German population and smaller numbers of Poles in Bukovina, Serbs, Croats, Slovaks and Banat Bulgarians, Ukrainians, Greeks, Jews, Turks and Tatars, Armenians, Russians, Afro-Romanians, and others.

The Germans of Romania represent one of the most significant historical ethnic minorities of Romania from the modern period onwards.

Biertan is a commune in Transylvania, Romania. The commune is composed of three villages: Biertan, Copșa Mare, and Richiș, each of which has a fortified church.

The Soviet occupation of Romania refers to the period from 1944 to August 1958, during which the Soviet Union maintained a significant military presence in Romania. The fate of the territories held by Romania after 1918 that were incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1940 is treated separately in the article on Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina.

Forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union was considered by the Soviet Union to be part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941–1945) of World War II. Soviet authorities deported German civilians from Germany and Eastern Europe to the USSR after World War II as forced laborers, while ethnic Germans living in the USSR were deported during World War II and conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

The Banat Swabians are an ethnic German population in the former Kingdom of Hungary in Central-Southeast Europe, part of the Danube Swabians and Germans of Romania. They emigrated in the 18th century to what was then the Austrian Empire's Banat of Temeswar province, later included in the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary, a province which had been left sparsely populated by the wars with the Ottoman Empire. At the end of World War I in 1918, the Swabian minority worked to establish an independent multi-ethnic Banat Republic; however, the province was divided by the Treaty of Versailles of 1919, and the Treaty of Trianon of 1920. The greater part was annexed by Romania, a smaller part by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and a small region around Szeged remained part of Hungary.

Demographic estimates of the flight and expulsion of Germans have been derived by either the compilation of registered dead and missing persons or by a comparison of pre-war and post-war population data. Estimates of the number of displaced Germans vary in the range of 12.0–16.5 million. The death toll attributable to the flight and expulsions was estimated at 2.2 million by the West German government in 1958 using the population balance method. German records which became public in 1987 have caused some historians in Germany to put the actual total at about 500,000 based on the listing of confirmed deaths. The German Historical Museum puts the figure at 600,000 victims and says that the official figure of 2 million did not stand up to later review. However, the German Red Cross still maintains that the total death toll of the expulsions is 2,251,500 persons.

The Bărăgan deportations were a large-scale action of penal transportation, undertaken during the 1950s by the Romanian Communist regime. Their aim was to forcibly relocate individuals who lived within approximately 25 km of the Yugoslav border to the Bărăgan Plain. The deportees were allowed to return after 1956.

The presence of German-speaking populations in Central and Eastern Europe is rooted in centuries of history, with the settling in northeastern Europe of Germanic peoples predating even the founding of the Roman Empire. The presence of independent German states in the region, and later the German Empire as well as other multi-ethnic countries with German-speaking minorities, such as Hungary, Poland, Imperial Russia, etc., demonstrates the extent and duration of German-speaking settlements.

The German Party was a political party in post-World War I Romania, claiming to represent the entire ethnic German community in the country, at the time it was still a kingdom.

The forced labour of Hungarians in the Soviet Union in the aftermath of World War II was not researched until the fall of Communism and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. While exact numbers are not known, it is estimated that up to 600,000 Hungarians were deported, including an estimated 200,000 civilians. An estimated 200,000 perished. Hungarian forced labour was part of a larger system of foreign forced labour in the Soviet Union.