Gustav Adolf Franz Brand was a German writer, egoist anarchist, and pioneering campaigner for the acceptance of male bisexuality and homosexuality.

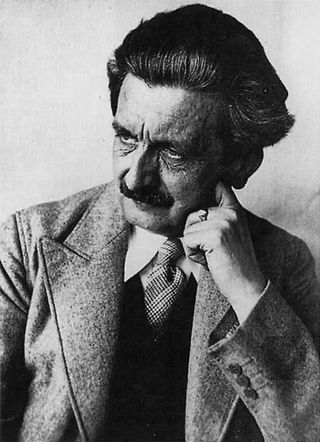

Friedrich Radszuweit was a German manager, publisher, and author and LGBT activist, who was of major importance to the first homosexual movement.

Claudia Schoppmann is a German historian and author.

Ruth Margarete Roellig was a German writer, she is known for documenting Berlin's lesbian club scene of the late 1920s during the Weimar Republic. Additionally she published support of Nazism starting in the 1930s, and she stopped writing after the end of World War II.

This is a list of events in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex (LGBTQ+) history in Germany.

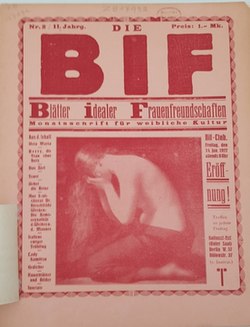

Die Freundin was a popular Weimar-era German lesbian magazine published from 1924 to 1933. Founded in 1924, it was the world's first lesbian magazine, closely followed by Frauenliebe and Die BIF. The magazine was published from Berlin, the capital of Germany, by the Bund für Menschenrecht, run by gay activist and publisher Friedrich Radszuweit. The Bund was an organization for homosexuals which had a membership of 48,000 in the 1920s.

Selma "Selli" Engler was a leading activist of the lesbian movement in Berlin from about 1924 to 1931.

Johanna Elberskirchen was a feminist writer and activist for the rights of women, gays and lesbians as well as blue-collar workers. She published books on women's sexuality and health among other topics. Her last known public appearance was in 1930 in Vienna, where she gave a talk at a conference organised by the World League for Sexual Reform. She was open about her own homosexuality which made her a somewhat exceptional figure in the feminist movement of her time. Her career as an activist was ended in 1933, when the Nazi Party rose to power. There is no public record of a funeral but witnesses report that Elberskirchen's urn was secretly put into the grave of Hildegard Moniac, who had been her life partner.

Garçonne was a Weimar-era German magazine for lesbians. It was published from 1926 to 1930 under the title Frauenliebe and from 1930 to 1932 as Garçonne.

Theodora "Theo" Anna Sprüngli, better known under the pseudonym Anna Rüling, was a German journalist whose speech in 1904 was the first political speech to address the problems faced by lesbians. One of the first modern women to come out as homosexual, she has been described as "the first known lesbian activist".

The following is a timeline of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) journalism history.

Emma Trosse was a German teacher and school administrator. Trained as a teacher and later passing an examination to be a principal, Trosse began her career working in public schools and as a private tutor. In 1895, she published one of the first scientific works on homosexuality and advocated for legal protections for homosexuals. She was the first known woman to scientifically discuss lesbianism. She also published books analyzing ancient medical practices in medieval Europe, and among the Greeks and Egyptians. After her marriage, she became a clinician in her husband's diabetes clinic, and began writing literature on diabetes.

Ilse Kokula is a German sociologist, educator, author and lesbian activist in the field of lesbian life. She was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Charlotte "Lotte" Hedwig Hahm was a prominent activist of the lesbian movement in Berlin during the Weimar Republic, National Socialist period, and after 1949, in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Elli Smula (1914–1943) was a Berlin tram conductor who was arrested in September 1940. She was accused of seriously compromising the Berlin Transport Authority (BVG) by failing to report for work after going out drinking with female fellow workers. Like her colleague Margarete Rosenberg, she was detained by the Gestapo in the prison on Alexanderplatz. BVG had received complaints that some of their female employees were taking their colleagues home, encouraging them to consume alcoholic drinks and involving them in lesbian sexual relationships. The following November both women were transferred to the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp where Smula "suddenly died" on 8 July 1943.

The Eldorado was the name of multiple nightclubs and performance venues in Berlin before the Nazi era and World War II. The name of the cabaret Eldorado has become an integral part of the popular iconography of the Weimar Republic. Two of the five locations the club occupied in its history are known to have catered to a gay crowd, although attendees would have included not only gay, lesbian, and bisexual patrons but also those identifying as heterosexual.

Das 3. Geschlecht, subtitled Die Transvestiten ("Transvestites"), was a transvestite magazine of Weimar Germany, published from 1930 until 1932 in Berlin. Published by the Radszuweit publishing house, it is believed to be the first transvestite magazine in history. A predecessor to the magazine was Die Freundin, a more lesbian-focused magazine that nonetheless published some columns appealing to transvestites.

In Nazi Germany, gay women who were sent to concentration camps were often categorized as "asocial", if they had not been otherwise targeted based on their ethnicity or political stances. Female homosexuality was criminalized in Austria, but not other parts of Nazi Germany. Because of the relative lack of interest of the Nazi state in female homosexuality compared to male homosexuality, there are fewer sources to document the situations of lesbians in Nazi Germany.

Käthe "Kati" Reinhardt, born Katharina Erika Selma Reinhardt, was a German activist in the lesbian movement. She was a formative figure in Berlin's lesbian subculture from the time of the Weimar Republic to the early 1980s as an organizer of clubs, balls, and meetings, and as a bar operator. In the 1920s she ran the largest clubs for the lesbian movement, which served up to 2,000 people, and worked, among others, with Charlotte “Lotte” Hahm.

Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes is a classic 1914 book on homosexuality in men and women that was written by German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. A second edition was published in 1920. Hirschfeld was himself gay and an occasional crossdresser, known by other Berlin crossdressers as "Aunt Magnesia". The book was part of the series Handbuch der Gesamten Sexualwissenschaft in Einzeldarstellungen and was the third volume of this series. Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes was not translated until 2000, under the title The Homosexuality of Men and Women by Michael Lombardi-Nash. It has been said that the book was the most significant and authoritative text on homosexuality of its time. The book has often been overlooked in the English-speaking academia.