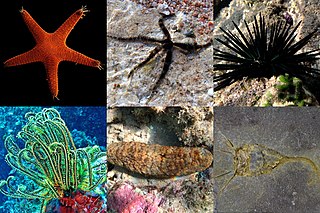

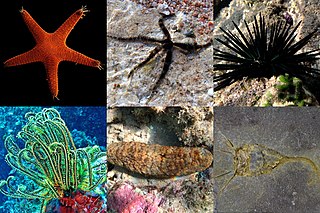

An echinoderm is any member of the phylum Echinodermata. The adults are recognisable by their radial symmetry, or pentamerous symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the sea lilies or "stone lilies". Adult echinoderms are found on the sea bed at every ocean depth, from the intertidal zone to the abyssal zone. The phylum contains about 7,000 living species, making it the second-largest grouping of deuterostomes, after the chordates. Echinoderms are the largest entirely marine phylum. The first definitive echinoderms appeared near the start of the Cambrian.

Crinoids are marine invertebrates that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their juvenile form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms, called feather stars or comatulids, are members of the largest crinoid order, Comatulida. Crinoids are echinoderms in the phylum Echinodermata, which also includes the starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins and sea cucumbers. They live in both shallow water and in depths as great as 9,000 meters (30,000 ft).

Sea urchins are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin are distributed on the seabeds of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to 5,000 meters. The spherical, hard shells (tests) of sea urchins are round and covered in spines. Most urchin spines range in length from 3 to 10 cm, with outliers such as the black sea urchin possessing spines as long as 30 cm (12 in). Sea urchins move slowly, crawling with tube feet, and also propel themselves with their spines. Although algae are the primary diet, sea urchins also eat slow-moving (sessile) animals. Predators that eat sea urchins include a wide variety of fish, starfish, crabs, marine mammals, and humans.

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea. Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish are also known as asteroids due to being in the class Asteroidea. About 1,900 species of starfish live on the seabed in all the world's oceans, from warm, tropical zones to frigid, polar regions. They are found from the intertidal zone down to abyssal depths, at 6,000 m (20,000 ft) below the surface.

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea. They are marine animals with a leathery skin and an elongated body containing a single, branched gonad. They are found on the sea floor worldwide. The number of known holothurian species worldwide is about 1,786, with the greatest number being in the Asia-Pacific region. Many of these are gathered for human consumption and some species are cultivated in aquaculture systems. The harvested product is variously referred to as trepang, namako, bêche-de-mer, or balate. Sea cucumbers serve a useful role in the marine ecosystem as they help recycle nutrients, breaking down detritus and other organic matter, after which bacteria can continue the decomposition process.

The water vascular system is a hydraulic system used by echinoderms, such as sea stars and sea urchins, for locomotion, food and waste transportation, and respiration. The system is composed of canals connecting numerous tube feet. Echinoderms move by alternately contracting muscles that force water into the tube feet, causing them to extend and push against the ground, then relaxing to allow the feet to retract.

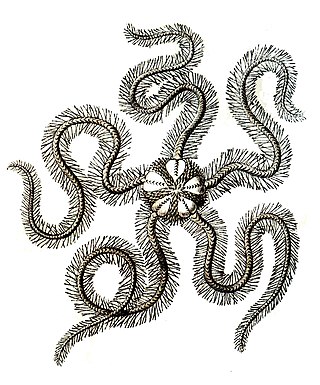

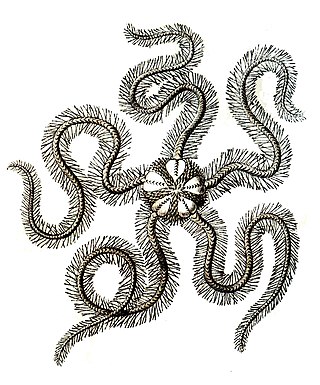

Brittle stars, serpent stars, or ophiuroids are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomotion. The ophiuroids generally have five long, slender, whip-like arms which may reach up to 60 cm (24 in) in length on the largest specimens.

Tube feet are small active tubular projections on the oral face of an echinoderm, whether the arms of a starfish, or the undersides of sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers; they are more discreet though present on brittle stars, and have only a feeding function in feather stars. They are part of the water vascular system.

Ambulacraria, or Coelomopora, is a clade of invertebrate phyla that includes echinoderms and hemichordates; a member of this group is called an ambulacrarian. Phylogenetic analysis suggests the echinoderms and hemichordates separated around 533 million years ago. The Ambulacraria are part of the deuterostomes, a clade that also includes the many Chordata, and the few extinct species belonging to the Vetulicolia.

Asthenosoma marisrubri, aka Red Sea fire urchin and toxic leather sea urchin , is a relatively common sea urchin with a widespread distribution in the Indo-Pacific, and was till 1998 considered a color variant of Asthenosoma varium. Sea urchins are close relatives of starfish, crinoids, brittle stars and sea cucumbers, all being echinoderms.

Synaptula lamperti is a species of sea cucumber in the family Synaptidae in the phylum Echinodermata, found on coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific region. The echinoderms are marine invertebrates and include the sea urchins, starfish and sea cucumbers. They are radially symmetric and have a water vascular system that operates by hydrostatic pressure, enabling them to move around by use of many suckers known as tube feet. Sea cucumbers are usually leathery, gherkin-shaped animals with a cluster of short tentacles at one end. They live on the sea bottom.

Luidia ciliaris, the seven-armed sea star, is a species of sea star (starfish) in the family Luidiidae. It is found in the eastern Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

Ophiocoma scolopendrina is a species of brittle star belonging to the family Ophiocomidae. Restricted to life in the intertidal, they live in the Indo-Pacific. They can typically be found within crevices or beneath borders on intertidal reef platforms. Unlike other Ophiocoma brittle stars, they are known for their unique way of surface-film feeding, using their arms to sweep the sea surface and trap food. Regeneration of their arms are a vital component of their physiology, allowing them to efficiently surface-film feed. These stars also have the ability to reproduce throughout the year, and have been known to have symbiotic relationships with other organisms.

Ossicles are small calcareous elements embedded in the dermis of the body wall of echinoderms. They form part of the endoskeleton and provide rigidity and protection. They are found in different forms and arrangements in sea urchins, starfish, brittle stars, sea cucumbers, and crinoids. The ossicles and spines are the only parts of the animal likely to be fossilized after an echinoderm dies.

Chantal Conand is a French marine biologist and oceanographer.

Actinopyga varians, the Pacific white-spotted sea cucumber or Hawaiian sea cucumber, is a species of sea cucumber in the family Holothuriidae. It is found in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii and also in the Indo-Pacific Ocean.

Ailsa McGown Clark (1926–2014) was a British zoologist, who principally studied echinoderms and was a specialist on asteroidea. She worked at the Natural History Museum for most of her career.