Samuel Gridley Howe was an American physician, abolitionist, and advocate of education for the blind. He organized and was the first director of the Perkins Institution. In 1824, he had gone to Greece to serve in the revolution as a surgeon. He arranged for support for refugees and brought many Greek children back to Boston with him for their education.

The institution of slavery in the European colonies in North America, which eventually became part of the United States of America, developed due to a combination of factors. Primarily, the labor demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were targets of enslavement by Europeans during the era.

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing. Involuntary servitude as a punishment for crime is still legal in the United States.

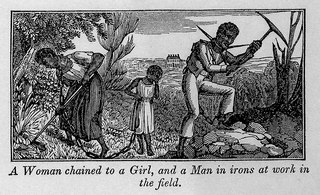

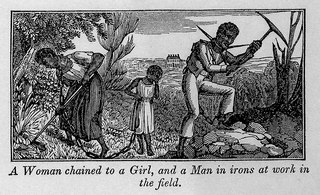

Child slavery is the slavery of children. The enslavement of children can be traced back through history. Even after the abolition of slavery, children continue to be enslaved and trafficked in modern times, which is a particular problem in developing countries.

Peon usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control over employment or economic conditions. Peon and peonage can refer to both the colonial period and post-colonial period of Latin America, as well as the period after the end of slavery in the United States, when "Black Codes" were passed to retain African-American freedmen as labor through other means.

Forty acres and a mule refers to a key part of Special Field Orders, No. 15 , a wartime order proclaimed by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman on January 16, 1865, during the American Civil War, to allot land to some freed families, in plots of land no larger than 40 acres (16 ha). Sherman later ordered the army to lend mules for the agrarian reform effort. The field orders followed a series of conversations between Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Radical Republican abolitionists Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens following disruptions to the institution of slavery provoked by the American Civil War. They provided for the confiscation of 400,000 acres (160,000 ha) of land along the Atlantic coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida and the dividing of it into parcels of not more than 40 acres (16 ha), on which were to be settled approximately 18,000 formerly enslaved families and other black people then living in the area.

The Black Codes, sometimes called the Black Laws, were laws which governed the conduct of African Americans. In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political privileges, between free white persons and free colored persons of African blood; and in no part of the country do the latter, in point of fact, participate equally with the whites, in the exercise of civil and political rights." Although Black Codes existed before the Civil War and although many Northern states had them, the Southern U.S. states codified such laws in everyday practice. The best known of these laws were passed by Southern states in 1865 and 1866, after the Civil War, in order to restrict African Americans' freedom, and in order to compel them to work for either low or no wages.

The Antebellum South era was a period in the history of the Southern United States that extended from the conclusion of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. This era was marked by the prevalent practice of slavery and the associated societal norms it cultivated. Over the course of this period, Southern leaders underwent a transformation in their perspective on slavery. Initially regarded as an awkward and temporary institution, it gradually evolved into a defended concept, with proponents arguing for its positive merits, while simultaneously vehemently opposing the burgeoning abolitionist movement.

Laura Smith Haviland was an American abolitionist, suffragette, and social reformer. She was a Quaker and an important figure in the history of the Underground Railroad.

The health of slaves on American plantations was a matter of concern to both slaves and their owners. Slavery had associated with it the health problems commonly associated with poverty. It was to the economic advantage of owners to keep their working slaves healthy, and those of reproductive age reproducing. Those who could not work or reproduce because of illness or age were sometimes abandoned by their owners, expelled from plantations, and left to fend for themselves.

Living in a wide range of circumstances and possessing the intersecting identity of both black and female, enslaved women of African descent had nuanced experiences of slavery. Historian Deborah Gray White explains that "the uniqueness of the African-American female's situation is that she stands at the crossroads of two of the most well-developed ideologies in America, that regarding women and that regarding the Negro." Beginning as early on in enslavement as the voyage on the Middle Passage, enslaved women received different treatment due to their gender. In regard to physical labor and hardship, enslaved women received similar treatment to their male counterparts, but they also frequently experienced sexual abuse at the hand of their enslavers who used stereotypes of black women's hypersexuality as justification.

The history of slavery in Kentucky dates from the earliest permanent European settlements in the state, until the end of the Civil War. In 1830, enslaved African Americans represented 24 percent of Kentucky's population, a share that declined to 19.5 percent by 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. Most enslaved people were concentrated in the cities of Louisville and Lexington and in the hemp- and tobacco-producing Bluegrass Region and Jackson Purchase. Other enslaved people lived in the Ohio River counties, where they were most often used in skilled trades or as house servants. Relatively few people were held in slavery in the mountainous regions of eastern and southeastern Kentucky, where they served primarily as artisans and service workers in towns.

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission, emancipation, or self-purchase. A fugitive slave is a person who escaped enslavement by fleeing.

The western part of Virginia which became West Virginia was settled in two directions, north to south from Pennsylvania, Maryland and New Jersey and from east to west from eastern Virginia and North Carolina. The earliest arrival of enslaved people was in the counties of the Shenandoah Valley, where prominent Virginia families built houses and plantations. The earliest recorded slave presence was about 1748 in Hampshire County on the estate of Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, which included 150 enslaved people. By the early 19th century, slavery had spread to the Ohio River up to the northern panhandle.

The 1842 Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation was the largest escape of a group of slaves to occur in the Cherokee Nation, in what was then Indian Territory. The slave revolt started on November 15, 1842, when a group of 20 African-Americans enslaved by the Cherokee escaped and tried to reach Mexico, where slavery had been abolished in 1829. Along their way south, they were joined by 15 slaves escaping from the Creek Nation in Indian Territory.

Slavery played the central role during the American Civil War. The primary catalyst for secession was slavery, especially Southern political leaders' resistance to attempts by Northern antislavery political forces to block the expansion of slavery into the western territories. Slave life went through great changes, as the Southern United States saw Union Armies take control of broad areas of land. During and before the war, enslaved people played an active role in their own emancipation, and thousands of enslaved people escaped from bondage during the war.

Nightjohn is a 1996 American television drama film directed by Charles Burnett and written by Bill Cain, based on the 1993 novel of the same name by Gary Paulsen. It aired on Disney Channel as one of its Premiere Films, on June 1, 1996.

The treatment of slaves in the United States sometimes included the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were occasionally split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

Slavery in Cuba was a portion of the larger Atlantic slave trade that primarily supported Spanish plantation owners engaged in the sugarcane trade. It was practiced on the island of Cuba from the 16th century until it was abolished by Spanish royal decree on October 7, 1886.

Slave marriages in the United States were typically illegal before the American Civil War abolished slavery in the US. Enslaved African Americans were legally considered chattel, and they were denied civil and political rights until the United States abolished slavery with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Both state and federal laws denied, or rarely defined, rights for enslaved people.