Dolle Dinsdag (English: Mad Tuesday) took place in the Netherlands (at the time occupied by Nazi Germany) on 5 September 1944, when celebrations were prompted after broadcasts incorrectly reported that Breda had been liberated by Allied forces.

Dolle Dinsdag (English: Mad Tuesday) took place in the Netherlands (at the time occupied by Nazi Germany) on 5 September 1944, when celebrations were prompted after broadcasts incorrectly reported that Breda had been liberated by Allied forces.

On 4 September 1944, the Allies conquered Antwerp, and it was thought that they had already advanced into the Netherlands. Radio Oranje broadcasts, one by the Prime Minister-in-exile Pieter Sjoerds Gerbrandy, increased the confusion; twice, in just over twelve hours (at 23:45 on 4 September and again in the morning of the 5th), they announced that Breda, 8 kilometers from the border with Belgium, had been liberated (though in fact this success would not be achieved until 29 October 1944, some eight weeks later, by forces of the 1st Polish Armoured Division of General Maczek). The news spread rapidly, with underground newspapers preparing headlines announcing the "fall of Breda".

Further fueling speculation, German occupation officials Arthur Seyss-Inquart (appointed Reichskommissar for the Occupied Netherlands in May 1940) and Hanns Albin Rauter, SS and police leader announced a "State of Siege" for the Netherlands to the 300,000 cable radio listeners and in the newspapers of the following day:

The population must maintain order ... it is strictly forbidden to flee areas that are threatened by the enemy. All orders from the military commanders must be strictly adhered to and without question ... any resistance to the occupation forces will be suppressed with force of weaponry. Any attempt to fraternize with the enemy or to hinder the German Reich and its allies in any form will be dealt with harshly; perpetrators will be shot.' [1]

Despite the threats, many Dutchmen celebrated on the streets while preparing to receive and cheer on the Allied liberators. Dutch and Orange flags and pennants were prepared, and many left their workplace to wait for the Allies to arrive. The extent of this optimism has been hard for historians to gauge in the absence of contemporary surveys, but it can be discerned as significant through researchers accessing diaries and finding an increase in births nine months after Dolle Dinsdag. [2] [3] [4] German occupation forces and NSB members panicked: documents were destroyed and many fled for Germany. Ary Willem Gijsbert Koppejan (1919–2013), a member of the resistance organisation De Ondergedoken Camera (the Underground Camera), secretly photographed German troops fleeing Den Haag and soldiers and collaborators waiting at the railway station. [5] [6] [7]

The Allied advance could not continue as the Allies had overextended themselves and halted in the South of the Netherlands and, as Operation Market Garden in September was an outright failure, the planned Allied advance across the Rhine had to be abandoned. The occupiers' nervousness turned to aggression after the landings in Normandy in June 1944 and increased after Dolle Dinsdag. [8] Due to the defeat of Operation Market Garden, the liberation of the remaining Dutch territory was postponed until the following spring, and the northern part of the Netherlands had to wait until 5 May 1945 for their liberation. This last winter under occupation became known as the “Hunger Winter", killing approximately 25,000 victims, [9] mostly elderly men, though the toll from its related health effects is likely to have been higher. [10] [11]

Mad Tuesday caused the railway strikes of 1944 that started on 17 September with the code: "De kinderen van Versteeg moeten onder de wol" (translation: the children of Versteeg must "get under the wool"/go to bed). The strike would last until the Netherlands was liberated fully on 5 May 1945; the government-in-exile thought that by spreading rumors the Germans would start to panic.[ citation needed ] This worked: by announcing the railway strike of 1944 the Germans started to panic even more, and many Germans and Dutch collaborators fled to Germany, fearing reprisals. (Seyss-Inquart had already set an example; on 3 September, he had sent his wife to Salzburg.) [12] The industry and supply rail route from and to Germany was almost completely inoperative, which made it even harder for Germany to defend what was still occupied.

The originator of the phrase "Dolle Dinsdag" is presumed to be Willem van den Hout, alias Willem W. Waterman, who first used it in a headline in the September 15 issue of his magazine De Gil ('The Yell', with 200,000 subscribers), though it had likely emerged in general usage before that. [13] De Gil satirised the NSB, the German occupiers, and the Dutch government-in-exile, but was actually funded by the Hauptabteilung für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda, the German propaganda department. [14]

The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands was a Dutch fascist and later Nazi political organisation that eventually became a political party. As a parliamentary party participating in legislative elections, the NSB had some success during the 1930s. Under German occupation, it remained the only legal party in the Netherlands during most of the Second World War.

Arthur Seyss-Inquart was an Austrian Nazi politician who served as Chancellor of Austria in 1938 for two days before the Anschluss. His positions in Nazi Germany included deputy governor to Hans Frank in the General Government of Occupied Poland, and Reich commissioner for the German-occupied Netherlands. In the latter role, he shared responsibility for the deportation of Dutch Jews and the shooting of hostages.

The Dutch famine of 1944–1945, also known as the Hunger Winter, was a famine that took place in the German-occupied Netherlands, especially in the densely populated western provinces north of the great rivers, during the relatively harsh winter of 1944–1945, near the end of World War II.

Anton Adriaan Mussert was a Dutch politician who co-founded the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (NSB) in 1931 and served as its leader until the party was banned in 1945. As such, he was the most prominent Dutch leader of the movement before and during World War II. Mussert collaborated with the German occupation government, but was granted little actual power and held the nominal title of Leider van het Nederlandsche Volk from 1942 onwards. In May 1945, as the war came to an end in Europe, Mussert was captured and arrested by Allied forces. He was charged and convicted of treason, and was executed in 1946.

Despite Dutch neutrality, Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands on 10 May 1940 as part of Fall Gelb. On 15 May 1940, one day after the bombing of Rotterdam, the Dutch forces surrendered. The Dutch government and the royal family relocated to London. Princess Juliana and her children sought refuge in Ottawa, Canada until after the war.

The Dutch resistance to the German occupation of the Netherlands during World War II can be mainly characterized as non-violent. The primary organizers were the Communist Party, churches, and independent groups. Over 300,000 people were hidden from German authorities in the autumn of 1944 by 60,000 to 200,000 illegal landlords and caretakers. These activities were tolerated knowingly by some one million people, including a few individuals among German occupiers and military.

Meinoud Marinus Rost van Tonningen was a Dutch politician of the National Socialist Movement (NSB). During the German occupation of the Netherlands in World War II, he collaborated extensively with the German occupation forces. He was the husband of Florentine Rost van Tonningen.

Johannes Hendrik Feldmeijer was a Dutch Nazi politician and a member of the NSB. He was the commander of the Sonderkommando-Feldmeijer death squad during Operation Silbertanne.

The Reichskommissariat Niederlande was the civilian occupation regime set up by Germany in the German-occupied Netherlands during World War II. Its full title was the Reich Commissariat for the Occupied Dutch Territories. The administration was headed by Arthur Seyss-Inquart, formerly the last chancellor of Austria before initiating its annexation by Germany.

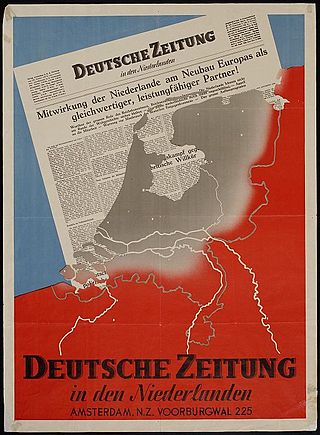

The Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden was a German-language nationwide newspaper based in Amsterdam, which was published during almost the entire occupation of the Netherlands in World War II from June 5, 1940 to May 5, 1945, the day of the German capitulation in the "Fortress Holland". Its objective was to influence the public opinion in the Netherlands, especially the one of the Germans in this country.

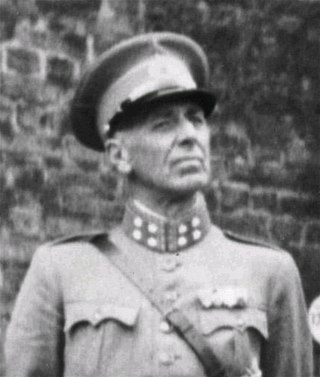

Hendrik Alexander Seyffardt was a Dutch general, who during World War II collaborated with Nazi Germany during the occupation of the Netherlands, most notably as a figurehead of the Volunteer Legion Netherlands, a unit of the Waffen-SS on the Eastern Front.

Wilhelm (Willi) Friedrich Adolf Ritterbusch, was a Nazi Party political functionary. Among other positions, he was the German Generalkommissar zur Besonderen Verwendung, directing the political affairs and propaganda in the occupied Netherlands from the middle of July 1943 until 7 May 1945, the end of World War II.

Events in the year 1944 in the Netherlands.

Events in the year 1945 in the Netherlands.

The Nederlandse Landwacht was a Dutch paramilitary organization founded by the German occupation forces in Holland on November 12, 1943. It should not be confused with the military volunteer corps 'Landwacht Nederland', which was established in March 1943 and renamed Landstorm Nederland in October, and which became part of the Waffen-SS.

The Netherlands Union was a short-lived political movement active in the German-occupied Netherlands in World War II. In its brief period of activity between July 1940 and May 1941, up to 800,000 Dutch people became members, which was about a tenth of the population at the time. It represented the largest political movement in the history of the Netherlands.

This timeline is about events during World War II of direct significance to the Netherlands. For a larger perspective, see Timeline of World War II.

The Netherlands Chamber of Culture was an institution established by Nazi Germany in the occupied Netherlands to regulate the production and distribution of art. Officially established on 25 November 1941, the chamber followed the model of the Reich Chamber of Culture in Germany and began operations on 22 January 1942. By 1 April of that year, all persons and institutions involved in the arts were required to register, with the former being demanded to submit an Aryan certificate and the latter being compelled to align their regulations with those of the chamber. By August 1944, the chamber had 42,000 registered members, from prominent artists to organ grinders.

Tobie Goedewaagen was a Dutch philosopher and politician. He served as the first secretary general of the Department of Public Information and the Arts, an institution established by the Nazi German occupation government, and led the Nederlandsche Kultuurkamer that had been established by the regime.

Sebastiaan Matheus Sigismund de Ranitz was a Dutch jurist and Nazi collaborator. He was the third and final Secretary-General of the Department of Public Information and the Arts, which was established by the civilian regime installed in the Netherlands by Nazi Germany during the occupation. He was charged in 1948 for being a member of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (NSB) and served six years in prison. After his imprisonment, he spent time as a business advisor.