Related Research Articles

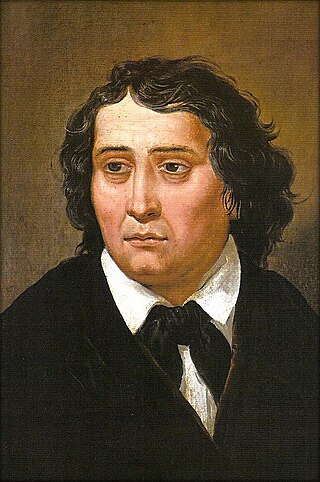

France Prešeren was a 19th-century Romantic Slovene poet whose poems have been translated into many languages.

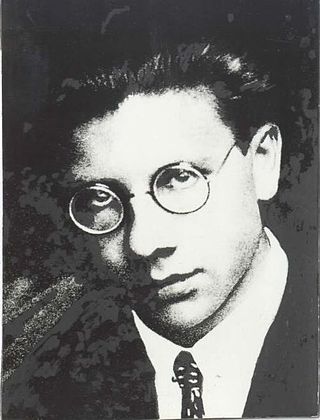

Ivan Cankar was a Slovene writer, playwright, essayist, poet, and political activist. Together with Oton Župančič, Dragotin Kette, and Josip Murn, he is considered as the beginner of modernism in Slovene literature. He is regarded as the greatest writer in Slovene, and has sometimes been compared to Franz Kafka and James Joyce.

Josip Murn, also known under the pseudonym Aleksandrov was a Slovene symbolist poet. Together with Ivan Cankar, Oton Župančič, and Dragotin Kette, he was regarded as one of the beginners of modernism in Slovene literature. After France Prešeren and Edvard Kocbek, Murn was probably the most influential Slovene poet of the last two centuries.

Oton Župančič was a Slovene poet, translator, and playwright. He is regarded, alongside Ivan Cankar, Dragotin Kette and Josip Murn, as the beginner of modernism in Slovene literature. In the period following World War I, Župančič was frequently regarded as the greatest Slovenian poet after Prešeren, but in the last forty years his influence has been declining and his poetry has lost much of its initial appeal.

Edvard Kocbek was a Slovenian poet, writer, essayist, translator, member of Christian Socialists in the Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation and Slovene Partisans. He is considered one of the best authors who have written in Slovene, and one of the best Slovene poets after Prešeren. His political role during and after World War II made him one of the most controversial figures in Slovenia in the 20th century.

France Balantič was a Slovene poet. His works were banned from schools and libraries during the Titoist regime in Slovenia, but since the late 1980s he has been re-evaluated as one of the foremost Slovene poets of the 20th century.

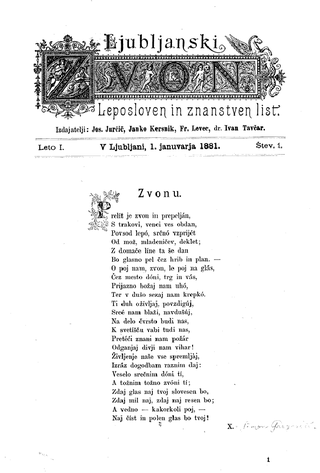

Ljubljanski zvon was a journal published in Ljubljana in Slovene between 1881 and 1941. It was considered one of the most prestigious literary and cultural magazines in Slovenia.

Janez Trdina was a Slovene writer and historian. The renowned author Ivan Cankar described him as the best Slovene stylist of his period. He was an ardent describer of the Gorjanci Ridge and of the Lower Carniolan region of Slovenia. Trdina Peak, the highest peak of Gorjanci Ridge, situated on the border between southeastern Slovenia and Croatia, was named for him in 1923.

Dušan Pirjevec, known by his nom de guerre Ahac, was a Slovenian Partisan, literary historian and philosopher. He was one of the most influential public intellectuals in post–World War II Slovenia.

Janko Kos is a Slovenian literary historian, theoretician, and critic.

Sodobnost is a Slovenian literary and cultural magazine, established in 1933. It is considered the oldest of currently existing literary magazines in Slovenia. Although Sodobnost has traditionally been a magazine focused on cultural and literary issues, it nowadays covers a wide range of current affairs. It is part of the Eurozine editorial project.

Izidor Cankar was a Slovenian author, art historian, diplomat, journalist, translator, and liberal conservative politician. He was one of the most important Slovenian art historians of the first part of the 20th century, and one of the most influential cultural figures in interwar Slovenia.

Alojzij Kuhar was a Slovenian and Yugoslav politician, diplomat, historian and journalist. Together with Izidor Cankar and Franc Snoj, he was an important exponent of the liberal conservative fraction of the Slovene People's Party.

France Vodnik (1903–1986) was a Slovenian literary critic, essayist, translator and poet from Ljubljana. He was mostly active in the interwar period, when Slovenia was part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He was the younger brother of the poet and critic Anton Vodnik.

Anton Vodnik was a Slovenian poet, art historian, and critic. He was one of the most notable representatives of Slovene Catholic expressionism in the interwar period.

Spomenka Hribar is a Slovenian author, philosopher, sociologist, politician, columnist, and public intellectual. She was one of the most influential Slovenian intellectuals in the 1980s, and was frequently called "the First Lady of Slovenian Democratic Opposition", and "the Voice of Slovenian Spring" She is married to the Slovenian Heideggerian philosopher Tine Hribar.

Kresnik is a literary award in Slovenia awarded each year for the best novel in Slovene of the previous year. It has been bestowed since 1991 at summer solstice by the national newspaper house Delo. The awards ceremony is normally held on Rožnik Hill above Ljubljana where the winner is invited to light a large bonfire. The winner also receives a financial award.

References

- 1 2 John Neubauer (2007). "Introduction". In Marcel Cornis-Pope & John Neubauer (ed.). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe. Vol. 3. John Benjamins. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-272-3455-1.

- 1 2 3 Péter Krasztev (2004). "From modernization to modernist literature". In Marcel Cornis-Pope & John Neubauer (ed.). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe. Vol. 1. John Benjamins. p. 336. ISBN 90-272-3452-3.

- ↑ Stanko Janež (1971). Živan Milisavac (ed.). Jugoslovenski književni leksikon[Yugoslav Literary Lexicon] (in Serbo-Croatian). Novi Sad (SAP Vojvodina, SR Serbia): Matica srpska. pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Ervin Dolenc (1996). "Culture, politics, and Slovene identity". In Jill Benderly & Evan Kraft (ed.). Independent Slovenia: Origins, Movements, Prospects. Macmillan. pp. 81–83. ISBN 0-312-16447-5.

- ↑ Marjan Dolgan (2001). Kriza revije Dom in svet leta 1937. ZRC SAZU. ISBN 961-6358-46-4.

- ↑ Aleš Gabrič (2001). "Slovenci in leto 1941". Odziv slovenskih kulturnikov na okupacijo leta 1941 [The response of Slovene cultural workers to the occupation in 1941]. Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino. pp. 211–224.